U.S. state

Bound together in a political union, each state holds governmental jurisdiction over a separate and defined geographic territory where it shares its sovereignty with the federal government.

All are grounded in republican principles (this being required by the federal constitution), and each provides for a government, consisting of three branches, each with separate and independent powers: executive, legislative, and judicial.

[17] A state, unlike the federal government, has un-enumerated police power, that is, the right to generally make all necessary laws for the welfare of its people.

[18] As a result, while the governments of the various states share many similar features, they often vary greatly with regard to form and substance.

[21] The term, commonwealth, which refers to a state in which the supreme power is vested in the people, was first used in Virginia during the Interregnum, the 1649–60 period between the reigns of Charles I and Charles II during which parliament's Oliver Cromwell as Lord Protector established a republican government known as the Commonwealth of England.

In Baker v. Carr (1962) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the U.S. Supreme Court held that all states are required to elect their legislatures in such a way as to afford each citizen the same degree of representation (the one person, one vote standard).

State governments commonly delegate some authority to local units and channel policy decisions down to them for implementation.

[29] In a few states, local units of government are permitted a degree of home rule over various matters.

The Cambridge Economic History of the United States says, "On the whole, especially after the mid-1880s, the Court construed the Commerce Clause in favor of increased federal power.

"[40] In 1941, the Supreme Court in U.S. v. Darby upheld the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, holding that Congress had the power under the Commerce Clause to regulate employment conditions.

[41] Then, one year later, in Wickard v. Filburn, the Court expanded federal power to regulate the economy by holding that federal authority under the commerce clause extends to activities which may appear to be local in nature but in reality effect the entire national economy and are therefore of national concern.

Subsequently, Congress invoked the Commerce Clause to expand federal criminal legislation, as well as for social reforms such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

Only within the past couple of decades, through decisions in cases such as those in U.S. v. Lopez (1995) and U.S. v. Morrison (2000), has the Court tried to limit the Commerce Clause power of Congress.

By threatening to withhold federal highway funds, Congress has been able to pressure state legislatures to pass various laws.

Although some objected that this infringes on states' rights, the Supreme Court upheld the practice as a permissible use of the Constitution's Spending Clause in South Dakota v. Dole 483 U.S. 203 (1987).

Seats in the House are distributed among the states in proportion to the most recent constitutionally mandated decennial census.

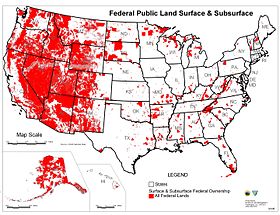

Most of the states admitted to the Union after the original 13 were formed from an organized territory established and governed by Congress in accord with its plenary power under Article IV, Section 3, Clause 2.

Upon acceptance of that constitution and meeting any additional congressional stipulations, Congress has always admitted that territory as a state.

In addition to the original 13, six subsequent states were never an organized territory of the federal government, or part of one, before being admitted to the Union.

In another, leaders of the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole) in Indian Territory proposed to establish the state of Sequoyah in 1905, as a means to retain control of their lands.

Among them, Michigan Territory, which petitioned Congress for statehood in 1835, was not admitted to the Union until 1837, due to a boundary dispute with the adjoining state of Ohio.

[64] Statehood for Kansas Territory was held up for several years (1854–61) due to a series of internal violent conflicts involving anti-slavery and pro-slavery factions.

West Virginia's bid for statehood was also delayed over slavery and was settled when it agreed to adopt a gradual abolition plan.

[66][67] The future political status of Guam has been a matter of significant discussion, with public opinion polls indicating a strong preference of becoming a U.S.

[70] A non-binding referendum on statehood, independence, or a new option for an associated territory (different from the current status) was held on November 6, 2012.

6246 Act was introduced on the U.S. House with the purpose of responding to, and comply with, the democratic will of the United States citizens residing in Puerto Rico as expressed in the plebiscites held on November 6, 2012, and June 11, 2017, by setting forth the terms for the admission of the territory of Puerto Rico as a state of the Union.

The question of whether or not individual states held the unilateral right to secession was a passionately debated feature of the nations' political discourse from early in its history and remained a difficult and divisive topic until the American Civil War.

The federal government never recognized the sovereignty of the CSA, nor the validity of the ordinances of secession adopted by the seceding states.

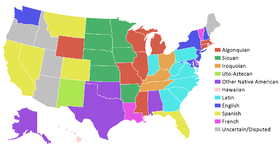

Territorial and new state lines often followed various geographic features (such as rivers or mountain range peaks), and were influenced by settlement or transportation patterns.

[83] The Census Bureau region definition (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West) is "widely used ... for data collection and analysis,"[84] and is the most commonly used classification system.

1776–1790 1791–1796

1803–1819 1820–1837

1845–1859 1861–1876

1889–1896 1907–1912

1959