Controversial invocations of the Patriot Act

In September 2003, The New York Times reported on a case of the USA PATRIOT Act being used to investigate alleged potential drug traffickers without probable cause.

The article also mentions a study by Congress that referenced hundreds of cases where the USA PATRIOT Act was used to investigate non-terrorist alleged future crimes.

Prohibiting a bill of attainder means that the US Congress cannot pass a law which deems a specific person or group guilty and then punish them without trial.

Previous legislation required that federal law enforcement destroy any records harvested during an investigation that pertained to anyone deemed innocent.

A few have filed suit, because the National Security Letters that they were presented with were very sweeping, demanding information not just on the individual under investigation, but on everyone who had used specific terminals at the libraries during given time windows.

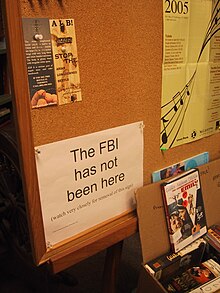

In June 2005, the United States House of Representatives voted to repeal the Patriot Act provision that had allowed federal agents to examine people's book-reading habits at public libraries and bookstores as part of terrorism investigations.

Police arriving at the scene found the equipment (which had been displayed in museums and galleries throughout Europe and North America) suspicious and notified the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

The next day the FBI, Joint Terrorism Task Force, Department of Homeland Security and numerous other law enforcement agencies arrived in HAZMAT gear and cordoned off the block surrounding Kurtz's house, impounding computers, manuscripts, books, and equipment, and detaining Kurtz without charge for 22 hours; the Erie County Health Department condemned the house as a possible "health risk" while the cultures were analyzed.

Although it was determined that nothing in the Kurtz's home posed any health or safety risk, the Justice Department sought charges under Section 175 of the US Biological Weapons Anti-Terrorism Act—a law which was expanded by the USA PATRIOT Act.

Supporters worldwide argue that this is a politically motivated prosecution, akin to those seen during the era of McCarthyism, and legal observers note that it is a precedent-setting case with far-reaching implications involving the criminalization of free speech and expression for artists, scientists, researchers, and others.

[12][13] FBI agents used a USA PATRIOT Act "sneak and peek" search to secretly examine the home of Brandon Mayfield, who was wrongfully jailed for two weeks on suspicion of involvement in the Madrid train bombings.

Prosecutors said the sites included religious edicts justifying suicide bombings and an invitation to contribute financially to the militant Palestinian organization Hamas.

[23] Plaintiffs joined by Michael Ferrari and Matt Garrison filed a second lawsuit on June 12, 2013 challenging the constitutionality of bulk metadata collection of both phone and Internet communications (Klayman II).

[25] In Klayman II, the plaintiffs sued the same government defendants and in addition, Facebook, Yahoo!, Google, Microsoft, YouTube, AOL, PalTalk, Skype, Sprint, AT&T, Apple again alleging the bulk metadata collection violates the First, Fourth and Fifth Amendment and constitutes divulgence of communication records in violation of Section 2702 of Stored Communications Act.

Citing possible secrecy provisions of the USA PATRIOT Act, the Department of Justice prevented the ACLU from releasing the text of a countersuit for three weeks.

"While the reauthorized Patriot Act is far from perfect, we succeeded in stemming the damage from some of the Bush administration's most reckless policies," said Ann Beeson, associate legal director of the ACLU.

In 2015, the Second Circuit appeals court ruled in ACLU v. Clapper that Section 215 of the Patriot Act did not authorize the bulk collection of phone metadata, which judge Gerard E. Lynch called a "staggering" amount of information.