1967 USS Forrestal fire

The flammable jet fuel spilled across the flight deck, ignited, and triggered a chain reaction of explosions that killed 134 sailors and injured 161.

After arrival at Yankee Station, aircraft from Attack Carrier Air Wing 17 flew approximately 150 missions against targets in North Vietnam over four days.

[5] The ongoing naval bombing campaign during 1967 originating at Yankee Station represented by far the most intense and sustained air attack operation in the U.S. Navy's history.

These lessons were gradually lost and by 1967, the U.S. Navy had reverted to the Japanese model at Midway and relied on specialized, highly trained damage control and firefighting teams.

They had been shown films during training of Navy ordnance tests demonstrating how a 1,000 lb bomb could be directly exposed to a jet fuel fire for a full ten minutes and still be extinguished and cooled without an explosive cook-off.

[11]: 126 However, these tests were conducted using the new Mark 83 1,000 lb bombs, which featured relatively stable Composition H6 explosive and thicker, heat-resistant cases, compared to their predecessors.

Some of the batch of AN-M65A1s Forrestal received were more than a decade old, having spent a portion of that exposed to the heat and humidity of Okinawa or Guam,[12] eventually being improperly stored in open-air Quonset huts at a disused ammunition dump on the periphery of Subic Bay Naval Base.

Forrestal's ordnance handlers had never even seen an AN-M65A1 before, and to their shock, the bombs delivered from Diamond Head were in terrible condition; coated with "decades of accumulated rust and grime" and still in their original packing crates (now moldy and rotten); some were stamped with production dates as early as 1953.

[11]: 87 [14][13] According to Lieutenant R. R. "Rocky" Pratt, a naval aviator attached to VA-106,[15] the concern felt by Forrestal's ordnance handlers was striking, with many afraid to even handle the bombs; one officer wondered out loud if they would survive the shock of a catapult-assisted launch without spontaneously detonating, and others suggested they immediately jettison them.

When notified that the bombs were actually destined for active service in the carrier fleet, the commanding officer of the naval ordnance detachment at Subic Bay was so shocked that he initially refused the transfer, believing a paperwork mistake had been made.

At the risk of delaying Diamond Head's departure, he refused to sign the transfer forms until receiving written orders from CINCPAC on the teleprinter, explicitly absolving his detachment of responsibility for the bombs' terrible condition.

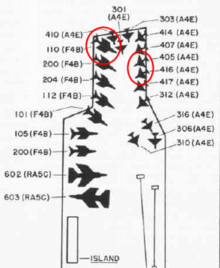

[11]: 273–274 While preparing for the second sortie of the day, the aft portion of the flight deck was packed wing-to-wing with twelve A-4E Skyhawk, seven F-4B Phantom II, and two RA-5C Vigilante aircraft.

[14] The rocket flew about 100 feet (30 m) across the flight deck, likely severing the arm of a crewman, and ruptured a 400-US-gallon (1,500 L; 330 imp gal) wing-mounted external fuel tank on a Skyhawk from Attack Squadron 46 (VA-46) awaiting launch.

[2] Lieutenant Commander John McCain stated in his 1999 book Faith of My Fathers that the missile struck his aircraft, alongside White's A-4 Skyhawk.

[19]: 34 The highly flammable JP-5 fuel spread on the deck under White's and McCain's A-4s, ignited by numerous fragments of burning rocket propellant, and causing an instantaneous conflagration.

[14] Based on their training, the team believed they had a ten-minute window to extinguish the fire before the bomb's casing would melt resulting in a low-order explosion.

Despite Farrier's constant effort to cool the bomb that had fallen to the deck, the casing suddenly split open and the explosive began to burn brightly.

The explosions and fire killed 50 night crew personnel who were sleeping in berthing compartments below the aft portion of the flight deck.

Another destroyer, USS Rupertus, maneuvered as close as 20 feet (6 m) to Forrestal for 90 minutes, directing her own on-board fire hoses at the burning flight and hangar deck on the starboard side, and at the port-side aft 5-inch gun mount.

Another sailor volunteered to be lowered by line through a hole in the flight deck to defuse a live bomb that had dropped to the 03 level—even though the compartment was still on fire and full of smoke.

He said it was extremely difficult to remove charred, blackened bodies locked in rigor mortis "while maintaining some sort of dignity for your fallen comrades.

On 31 July, Forrestal arrived at Naval Air Station Cubi Point in the Philippines, to undertake repairs sufficient to allow the ship to return to the United States.

[20] A special group, the Aircraft Carrier Safety Review Panel, led by Rear Admiral Forsyth Massey, was convened on 15 August in the Philippines.

[1] The board of investigation stated, "Poor and outdated doctrinal and technical documentation of ordnance and aircraft equipment and procedures, evident at all levels of command, was a contributing cause of the accidental rocket firing."

They had agreed on a deviation from standard procedure: to "Allow ordnance personnel to connect pigtails 'in the pack', prior to taxi, leaving only safety pin removal at the cat."

[1] From 19 September 1967 to 8 April 1968, Forrestal underwent repairs in Norfolk Naval Shipyard, beginning with removal of the starboard deck-edge elevator, which was stuck in place.

This accident was caused by the landing aircraft being illuminated by carrier based radar, and the resulting EMI sent an unwanted signal to the weapons system.

[46] The fire revealed that Forrestal lacked a heavy-duty, armored forklift needed to jettison aircraft, particularly heavier planes like the RA-5C Vigilante, as well as heavy or damaged ordnance.

In response, a "wash-down" system, which floods the flight deck with foam or water, was incorporated into all carriers, with the first being installed aboard Franklin D. Roosevelt during her 1968–1969 refit.

Recruits are tested on their knowledge and skills by having to use portable extinguishers and charged hoses to fight fires, as well as demonstrating the ability to egress from compartments that are heated and filled with smoke.