Protectorate of Uganda

In the mid-1880s, the Kingdom of Buganda was divided between four religious factions – Adherents of Uganda's Native Religion, Catholics, Protestants and Muslims – each vying for political control.

This coalition secured an alliance with the Imperial British East Africa Company (IBEAC), and succeeded in ousting Kalema and reinstating Mwanga in 1890.

[4] Although momentous change occurred during the colonial era in Uganda, some characteristics of late-nineteenth-century African society survived to reemerge at the time of independence.

The chiefs were more interested in preserving Uganda as a self-governing entity, continuing the royal line of Kabakas, and securing private land tenure for themselves and their supporters.

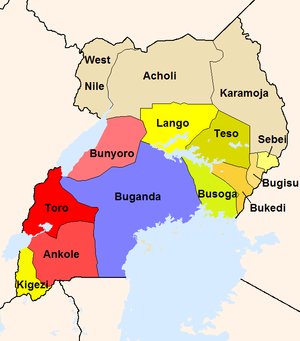

The British signed much less generous treaties with the other kingdoms (Toro in 1900, Ankole in 1901, and Bunyoro in 1933) without the provision of large-scale private land tenure.

A major part of the territory eventually left out of the "East Africa Protectorate" was the Uganda Scheme, in which the British Empire offered to create a Jewish nation-state.

Even the CMS joined the effort by launching the Uganda Company (managed by a former missionary) to promote cotton planting and to buy and transport the produce.

The advantages of this crop were quickly recognized by the Baganda chiefs who had newly acquired freehold estates, which came to be known as mailo because they were measured in square miles.

The chief minister of the Buganda kingdom, Sir Apollo Kaggwa, personally awarded a bicycle to the top graduate at King's College Budo, together with the promise of a government job.

The schools, in fact, had inherited the educational function formerly performed in the Kabaka's palace, where generations of young pages had been trained to become chiefs.

But Kabaka Daudi never gained real political power, and after a short and frustrating reign, he died at the relatively young age of forty-three.

[8] On 1 January 1902[9] the somewhat irregular armed force in Uganda was reformed (with far fewer Sudanese and more local tribes in its ranks)[8] and re-titled the 4th Battalion the King's African Rifles (KAR).

Far more promising as a source of political support were the British colonial officers, who welcomed the typing and translation skills of school graduates and advanced the careers of their favourites.

The contest was decided after World War I, when an influx of British ex-military officers, now serving as district commissioners, began to feel that self-government was an obstacle to good government.

Specifically, they accused Sir Apollo and his generation of inefficiency, abuse of power, and failure to keep adequate financial accounts—charges that were not hard to document.

Thus the oligarchy of landed chiefs who had emerged with the Uganda Agreement of 1900 declined in importance, and agricultural production shifted to independent smallholders, who grew cotton, and later coffee, for the export market.

Unlike Tanganyika, which was devastated during the prolonged fighting between Britain and Germany in the East African Campaign of World War I, Uganda prospered from wartime agricultural production.

The colonial government strictly regulated the buying and processing of cash crops, setting prices and reserving the role of intermediary for Asians, who were thought to be more efficient.

The effects of Britain's postwar withdrawal from India, the march of nationalism in West Africa, and a more liberal philosophy in the Colonial Office geared toward future self-rule all began to be felt in Uganda.

The embodiment of these issues arrived in 1952 in the person of a new and energetic reformist governor, Sir Andrew Cohen (formerly undersecretary for African affairs in the Colonial Office).

On the economic side, he removed obstacles to African cotton ginning, rescinded price discrimination against African-grown coffee, encouraged cooperatives, and established the Uganda Development Corporation to promote and finance new projects.

On the political side, he reorganized the Legislative Council, which had consisted of an unrepresentative selection of interest groups heavily favouring the European community, to include African representatives elected from districts throughout Uganda.

The spark that ignited wider opposition to Governor Cohen's reforms was a 1953 speech in London in which the secretary of state for colonies referred to the possibility of a federation of the three East African territories (Kenya, Uganda, and Tanganyika), similar to that established in Rhodesia and Nyasaland.

Many Ugandans were aware of the Central African Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland (later Zimbabwe, Zambia, and Malawi) and its domination by white settler interests.

Confidence in Cohen vanished just as the Governor was preparing to urge Buganda to recognize that its special status would have to be sacrificed in the interests of a new and larger nation-state.

His forced departure made the Kabaka an instant martyr in the eyes of the Baganda, whose latent separatism and anticolonial sentiments set off a storm of protest.

In 1960 a political organizer from Lango, Milton Obote, seized the initiative and formed a new party, the Uganda People's Congress (UPC), as a coalition of all those outside the Roman Catholic-dominated DP who opposed Buganda hegemony.

The steps Cohen had initiated to bring about the independence of a unified Ugandan state had led to a polarization between factions from Buganda and those opposed to its domination.

The British announced that elections would be held in March 1961 for "responsible government", the next-to-last stage of preparation before the formal granting of independence.

Shocked by the results, the Baganda separatists, who formed a political party called Kabaka Yekka, had second thoughts about the wisdom of their election boycott.