Unihemispheric slow-wave sleep

[1] USWS offers a number of benefits, including the ability to rest in areas of high predation or during long migratory flights.

[2] The greatest theoretical importance of USWS is its potential role in elucidating the function of sleep by challenging various current notions.

In the past, aquatic animals, such as dolphins and seals, had to regularly surface in order to breathe and regulate body temperature.

Due to their poorly webbed feet and long wings, which are not completely waterproof, it is not energetically efficient for them to make rest stops or land on water, only to take flight again.

However, in USWS, the maximal release of the cortical acetylcholine neurotransmitter is lateralized to the hemisphere exhibiting an EEG trace resembling wakefulness.

[1] In domestic chicks and other species of birds exhibiting USWS, one eye remained open contra-lateral (on the opposite side) to the "awake" hemisphere.

[8] This has also been shown to be the favored behavior of belugas, although inconsistencies have arisen directly relating the sleeping hemisphere and open eye.

[9] Keeping one eye open aids birds in engaging in USWS while mid-flight as well as helping them observe predators in their vicinity.

[11] Given that USWS is preserved also in blind animals or during a lack of visual stimuli, it cannot be considered as a consequence of keeping an eye open while sleeping.

Although unilateral vision plays a considerable role in keeping active the contralateral hemisphere, it is not the motive power of USWS.

Other evidence contradicts this potential role; sagittal transsections of the corpus callosum have been found to result in strictly bihemispheric sleep.

Some studies have shown induced asynchronous SWS in non-USWS-exhibiting animals as a result of sagittal transactions of subcortical regions, including the lower brainstem, while leaving the corpus callosum intact.

Other comparisons found that mammals exhibiting USWS have a larger posterior commissure and increased decussation of ascending fibres from the locus coeruleus in the brainstem.

This is consistent with the fact that one form for neuromodulation, the noradrenergic diffuse modulatory system present in the locus coeruleus, is involved in regulating arousal, attention, and sleep-wake cycles.

The continuous discharge of noradrenergic neurons stimulates heat production: the awake hemisphere of dolphins shows a higher, but stable, temperature.

Complete decussation of the optic tract has been seen as a method of ensuring the open eye strictly activates the contralateral hemisphere.

Unihemispheric sleep allows visual vigilance of the environment, preservation of movement, and in cetaceans, control of the respiratory system.

Since USWS allows for the one eye to be open, the cerebral hemisphere that undergoes slow-wave sleep varies depending on the position of the bird relative to the rest of the flock.

[7] Bottlenose dolphins are one specific species of cetaceans that have been proven experimentally to use USWS in order to maintain both swimming patterns and the surfacing for air while sleeping.

[10] Although humans show reduced left-hemisphere delta waves during slow-wave sleep in an unfamiliar bedchamber, this is not wakeful alertness of USWS.

[10] Multiple other species of birds have also been found to exhibit USWS including Recent studies have illustrated that the white-crowned sparrow, as well as other passerines, have the capability of sleeping most significantly during the migratory season while in flight.

Free-flying birds might be able to spend some time sleeping while in non-migratory flight as well when in the unobstructed sky as opposed to in controlled captive conditions.

A method of recording brain activity in pigeons during flight has recently proven promising in that it could obtain an EEG of each hemisphere but for relatively short periods of time.

Coupled with simulated wind tunnels in a controlled setting, these new methods of measuring brain activity could elucidate the truth behind whether or not birds sleep during flight.

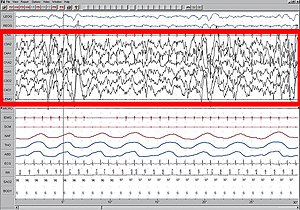

High amplitude EEG is highlighted in red.