Polarity (international relations)

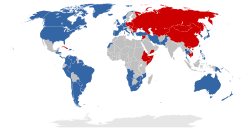

One generally distinguishes three types of systems: unipolarity, bipolarity, and multipolarity for three or more centers of power.

[1] The type of system is completely dependent on the distribution of power and influence of states in a region or globally.

Kenneth Waltz and John Mearsheimer are among those who argue that bipolarity tends to generate relatively more stability.

Liberal institutionalist John Ikenberry argues in a series of influential writings that the United States purposely set up an international order after the end of World War II that sustained U.S.

U.S. strategic restraint allowed weaker countries to participate in the make-up of the post-war world order, which limited opportunities for the United States to exploit total power advantages.

Ikenberry notes that while the United States could have unilaterally engaged in unfettered power projection, it decided instead to "lock in" its advantage long after zenith by establishing an enduring institutional order, gave weaker countries a voice, reduced great power uncertainty, and mitigated the security dilemma.

The liberal basis of U.S. hegemony—a transparent democratic political system—has made it easier for other countries to accept the post-war order, Ikenberry explains.

"[20][8] Scholars have debated whether the current (in 2024) international order is characterized by unipolarity, bipolarity or multipolarity.

[24] In 2023, Wohlforth and Stephen Brooks argued that the United States is still the unipole but that U.S. power has weakened and the nature of U.S. unipolarity has changed.

Yes, the United States has become less dominant over the past 20 years, but it remains at the top of the global power hierarchy—safely above China and far, far above every other country... Other countries simply cannot match the power of the United States by joining alliances or building up their militaries.

"Wide latitude" of "policy choices" will allow the U.S. to act capriciously on the basis of "internal political pressure and national ambition.

"Unbalanced power leaves weaker states feeling uneasy and gives them reason to strengthen their positions," Waltz says.

[29] In a 2021 study, Yuan-kang Wang argues from the experience of Ming China (1368–1644) and Qing China (1644–1912) that the durability of unipolarity is contingent on the ability of the unipole to sustain its power advantage and for potential challengers to increase their power without provoking a military reaction from the unipole.

Kenneth Waltz's influential Theory of International Politics argued that bipolarity tended towards the greatest stability because the two great powers would engage in rapid mutual adjustment, which would prevent inadvertent escalation and reduce the chance of power asymmetries forming.

[5] John Mearsheimer also argued, that bipolarity is the most stable form of polarity, as buck passing is less frequent.

[33] Dale C. Copeland has challenged Waltz on this, arguing that bipolarity creates a risk for war when a power asymmetry or divergence happens.

[41] Thomas Christensen and Jack Snyder argue that multipolarity tends towards instability and conflict escalation due to "chain-ganging" (allies get drawn into unwise wars provoked by alliance partners) and "buck-passing" (states which do not experience an immediate proximate threat do not balance against the threatening power in the hope that others carry the cost of balancing against the threat).

Though, Mearsheimer predicts the persistence of a thin international order within multipolarity, which constitutes some multilateral agreements.