Society of United Irishmen

Espousing principles they believed had been vindicated by American independence and by the French Declaration of the Rights of Man, the Presbyterian merchants who formed the first United society in Belfast in 1791 vowed to make common cause with their Catholic-majority fellow countrymen.

Since the rebellion's centenary in 1898, Ireland's major political traditions, unionist, nationalist and republican, have claimed and disputed the legacy of the United Irishmen, and of the union they sought to effect between Catholic, Protestant and Dissenter.

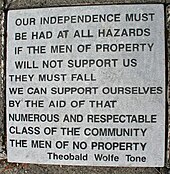

With the exception of Thomas Russell, a former India-service army officer originally from Cork, and Theobald Wolfe Tone, a Dublin barrister, the participants who resolved to reform the government of Ireland on "principles of civil, political and religious liberty"[2] were Presbyterians.

Swayed by Crown patronage, parliament, in any case, exercised little hold upon the executive, the Dublin Castle administration which through the office of the Lord Lieutenant continued to be appointed by the King's ministers in London.

In 1783 Volunteers converged again upon Dublin, this time to support a bill presented by Grattan's patriot rival, Henry Flood, to abolish the proprietary boroughs and to extend the existing, Protestant, forty-shilling freehold county franchise.

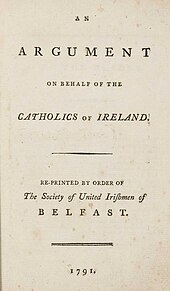

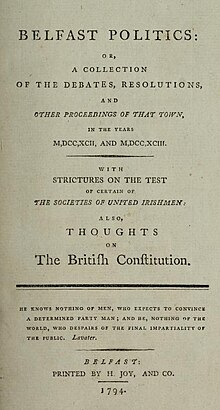

[27][28] They urged their fellow countrymen to follow their example: to "form similar Societies in every quarter of the kingdom for the promotion of Constitutional knowledge, the abolition of bigotry in religion and policies, and the equal distribution of the Rights of Man through all Sects and Denominations of Irishmen".

History, in any case, was reassuring: when they had the opportunity in the Parliament summoned by James II in 1689, and clearer title to what had been forfeit not ninety but forty years before (in the Cromwellian Settlement), Catholics did not insist upon a wholesale return of their lost estates.

William Steel Dickson, with "keen irony", wondered whether Catholics were to ascend the "ladder" to liberty "by intermarrying with the wise and capable Protestants, and particularly with us Presbyterians, [so that] they may amend the breed, and produce a race of beings who will inherit the capacity from us?

[43] Beyond the inclusion of Catholics and a re-distribution of seats, Tone and Russell protested that it was unclear what members were pledging themselves to in Drennan's original "test": "an impartial and adequate representation of the Irish nation in parliament" was too vague and compromising.

[51][49]: 471 In May, delegates in Belfast representing 72 societies in Down and Antrim rewrote Drennan's test to pledge members to "an equal, full and adequate representation of all the people of Ireland", and to drop the reference to the Irish Parliament (with its Lords and Commons).

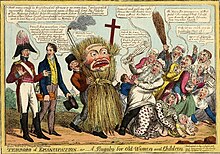

[7]: 135 In Antrim thousands filled fields to hear the itinerant Reformed preacher William Gibson prophesy – in the tradition that saw the Antichrist defeated in the overthrow of the Catholic Church in France[87] – the "immediate destruction of the British monarchy".

[98] In June 1795, four members of the Ulster executive – Neilson, Russell, McCracken and Robert Simms – met with Tone as he passed through Belfast en route to America and atop Cave Hill swore their celebrated oath "never to desist in our efforts until we had subverted the authority of England over our country, and asserted our independence'".

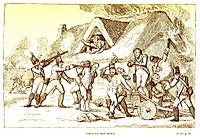

[103] A vigilante response to Peep O'Day raids upon Catholic homes in the mid-1780s, by the early 1790s the Defenders (drawing, like the United Irishmen, on the lodge structure of the Masons) were a secret oath-bound fraternity ranging across Ulster and the Irish midlands.

[106] With their brother-in-law John Magennis, in 1795 the United Irish brothers, Bartholomew and Charles Teeling, sons of a wealthy Catholic linen manufacturer in Lisburn, appear to have had command over the Down, Antrim and Armagh Defenders.

Suspecting that their object remained "selfish" (i.e. focused on emancipation rather than on separation and democratic reform) and recognizing their alarm at the anti-clericalism of the French Republic, Drennan, up until his trial for sedition in May 1794, promoted what he called an "inner Society" in Dublin, "Protestant but National".

[117] Lingering hopes of a return to open agitation were dashed in March the following year when, after endorsing Catholic admission to Parliament, the newly arrived Lord Lieutenant, William Fitzwilliam was summarily recalled.

Political tours by United Irishmen in the winter of 1796–7, and as conditions deteriorated in Ulster a growing tide of migrants, helped to promote such thinking and foster an interest in establishing societies on the new model Irish example.

In the north, the United societies had not recovered from their decapitation the previous September through the arrests (personally supervised by Castlereagh) that, in addition to Neilson, had netted Thomas Russell, Charles Teeling, Henry Joy McCracken and Robert Simms.

The senior Dublin Castle secretary, Edward Cooke, could write: "The quiet of the North is to me unaccountable; but I feel that the Popish tinge of the rebellion, and the treatment of France to Switzerland [the Protestant Cantons were resisting occupation] and America [the Quasi naval war], has really done much, and, in addition to the army, the force of Orange yeomanry is really formidable.

"[70]: 169 In response to the claim that "in Ulster, there are 50,000 men with arms in their hands, ready to receive the French," the Westminster Commons was assured that while "almost all Presbyterians... were attached to the popular, or, what has been called, the republican branch of the constitution, they are not to be confounded with Jacobins or banditti".

[159] On the eve of following his leader to the gallows, one of McCracken's lieutenants, James Dickey, is reported by Henry Joy (a hostile witness) as saying: "the Presbyterians of the north perceived too late that if they had succeeded in their designs, they would ultimately have had to contend with the Roman Catholics".

The authorities were persuaded in May 1799 that County Down had been "re-regimented and re-officered" and until the spring of 1802, while hopes could still be entertained of a French landing, United veterans continued night-time arms raids and assaults upon loyalists, especially in Antrim.

[174] On the promise of arms, Dwyer's guerrilla fighters in Wicklow and men in Kildare had been willing to act, but in the north, Russell and Hope found in United and Defender veterans alike the spirit of rebellion quite broken.

[178] A French Irish Legion (reinforced by 200 former United Irishmen sold by the British government as indentured mine labourers to Prussia, and joined for a time by William Dowdall and Arthur O'Connor)[166] was redeployed to counter-insurgency in Spain.

[180] In October 1799, Castlereagh received a report from Jamaica that many United Irish prisoners, "incautiously drafted" into regiments for service in the West Indies, had taken to the hills to fight alongside the Maroons and "such of the French as were in the island".

[181][182] The alarm spoke to a fear current both in the West Indies and in the United States (then engaged in its own Quasi War with the French) that Irish Jacobins would conspire in the cause not only of France but also of her putative allies, her former slaves in the Haitian Revolution.

[183] Protesting the Alien and Sedition Acts, in an open letter to George Washington one of their principals, William Duane (former editor in London of the LCS paper The Telegraph),[189] defended a vision of citizenship capable both of encompassing "the Jew, the savage, the Mahometan, the idolator, upon all of whom the sun shines equally", and of conceding "the right of the people to make and alter their constitutions of government".

[197] See also Irish Rebellion of 1798: "Contested commemoration" It was not the fulfilment of their hopes, but some United Irishmen sought vindication in the Acts of Union that in 1801 abolished the parliament in Dublin and brought Ireland directly under the Crown in Westminster.

Had their forefathers been offered a Union under the constitution as it later developed there would have been "no rebellion": "Catholic Emancipation, a Reformed Parliament, a responsible Executive and equal laws for the whole Irish people – these", they maintain, were "the real objects of the United Irishmen".

Surely you are not foolish enough to think that society could exist without landlords, without magistrates, without rulers... Be persuaded that it is quite out of the sphere of country farmers and labourers to set up as politicians, reformers, and law makers... What Townsend and the Ascendancy feared most of all were "the manifestations of an incipient Irish democracy".