Province of Canada

Its formation reflected recommendations made by John Lambton, 1st Earl of Durham, in the Report on the Affairs of British North America following the Rebellions of 1837–1838.

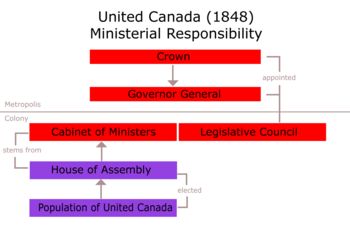

The Act of Union 1840, passed on 23 July 1840 by the British Parliament and proclaimed by the Crown on 10 February 1841,[3] merged the Colonies of Upper Canada and Lower Canada by abolishing their separate parliaments and replacing them with a single one with two houses, a Legislative Council as the upper chamber and the Legislative Assembly as the lower chamber.

Secondly, unification was an attempt to swamp the French vote by giving each of the former provinces the same number of parliamentary seats, despite the larger population of Lower Canada.

The first stage of this construction was completed in 1865, just in time to host the final session of the last parliament of the Province of Canada before Confederation in 1867.

[5] The Governor General remained the head of the civil administration of the colony, appointed by the British government, and responsible to it, not to the local legislature.

Sydenham came from a wealthy family of timber merchants, and was an expert in finance, having served on the English Board of Trade which regulated banking (including the colony).

He was promised a barony if he could successfully implement the union of the Canadas, and introduce a new form of municipal government, the District Council.

The aim of both exercises in state-building was to strengthen the power of the Governor General, to minimise the effect of the numerically superior French vote, and to build a "middle party" that answered to him, rather than the Family Compact or the Reformers.

His efforts to prevent the election of Louis LaFontaine, the leader of the French reformers, were foiled by David Willson, the leader of the Children of Peace, who convinced the electors of the 4th Riding of York to transcend linguistic prejudice and elect LaFontaine in an English-speaking riding in Canada West.

While LaFontaine was easily re-elected in 4th York, Baldwin lost his seat in Hastings as a result of Orange Order violence.

Lacking the scale of the American Revolution, it nonetheless forced a comparable articulation and rethinking of the basics of political dialogue in the province.

[11] Cathcart had been a staff officer with Wellington in the Napoleonic Wars, and rose in rank to become commander of British forces in North America from June 1845 to May 1847.

He was also appointed as Administrator then Governor General for the same period, uniting for the first time the highest Civil and military offices.

The appointment of this military officer as Governor General was due to heightened tensions with the United States over the Oregon boundary dispute.

Cathcart was deeply interested in the natural sciences, but ignorant of constitutional practice, and hence an unusual choice for Governor General.

Elgin invited LaFontaine to form the new government, the first time a Governor General requested cabinet formation on the basis of party.

Municipal government in Upper Canada was under the control of appointed magistrates who sat in Courts of Quarter Sessions to administer the law within a District.

[16] The Councils were reformed by the Baldwin Act in 1849 which made municipal government truly democratic rather than an extension of central control of the Crown.

It also established a hierarchy of types of municipal governments, starting at the top with cities and continued down past towns, villages and finally townships.

Their support was concentrated among southwestern Canada West farmers, who were frustrated and disillusioned by the 1849 Reform government of Robert Baldwin and Louis-Hippolyte Lafontaine's lack of democratic enthusiasm.

The Clear Grits advocated universal male suffrage, representation by population, democratic institutions, reductions in government expenditure, abolition of the Clergy reserves, voluntarism, and free trade with the United States.

Early Governors of the province were closely involved in political affairs, maintaining a right to make Executive Council and other appointments without the input of the legislative assembly.

[citation needed] However, in 1848 the Earl of Elgin, then Governor General, appointed a Cabinet nominated by the majority party of the Legislative Assembly, the Baldwin–Lafontaine coalition that had won elections in January.

Lord Elgin upheld the principles of responsible government by not repealing the Rebellion Losses Bill, which was highly unpopular with some English-speaking Loyalists who favoured imperial over majority rule.

The granting of responsible government to the colony is typically attributed to reforms in 1848 (principally the effective transfer of control over patronage from the Governor to the elected ministry).

In the end, the legislative deadlock between English and French led to a movement for a federal union which resulted in the broader Canadian Confederation in 1867.

In "The Liberal Order Framework: A Prospectus for a Reconnaissance of Canadian History" McKay argues that "the category 'Canada' should henceforth denote a historically specific project of rule, rather than either an essence we must defend or an empty homogeneous space we must possess.

"[21] The liberalism of which McKay writes is not that of a specific political party, but of certain practices of state building which prioritise property, first of all, and the individual.

In 1857, the Legislature introduced the Gradual Civilization Act, putting into law the principle that Indigenous persons should become British subjects and discard their Indian status, in exchange for a grant of land.