1950 United States Senate election in California

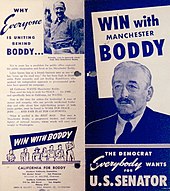

In March 1950, Downey withdrew from a vicious primary battle with Douglas by announcing his retirement, after which Los Angeles Daily News publisher Manchester Boddy joined the race.

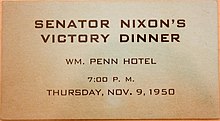

Nixon's attacks were far more effective, and he won the November 7 general election by almost 20 percentage points, carrying 53 of California's 58 counties and all metropolitan areas.

Other reasons for the result have been suggested, ranging from tepid support for Douglas from President Truman and his administration to the reluctance of voters in 1950 to elect a woman.

The campaign gave rise to two political nicknames, both coined by Boddy or making their first appearance in his newspaper: "the Pink Lady" for Douglas and "Tricky Dick" for Nixon.

[5] While the Daily News had not endorsed the Sinclair–Downey ticket,[a] Boddy had called Sinclair "a great man" and allowed the writer-turned-gubernatorial candidate to set forth his views on the newspaper's front page.

[12] However, other than Downey, most major California officeholders were Republican, including Governor Earl Warren (who was seeking a third term in 1950) and Senator William Knowland.

[18] Downey, who suffered from a severe ulcer, was initially undecided about running, but announced his candidacy in early December in a speech that included an attack on Douglas.

[22] In January 1950, Douglas opened campaign headquarters in Los Angeles and San Francisco, which was seen as a signal that she was serious about contesting Downey's seat and would not withdraw from the race.

[22] However, on March 29, amid rumors that he was doing badly in the polls, Downey announced both his retirement and his endorsement of Los Angeles Daily News publisher Manchester Boddy.

[28] Douglas called Downey's departure in favor of the publisher a cheap gimmick[24] and made no attempt to reach a rapprochement with the senator,[29] who entered Bethesda Naval Hospital for treatment in early April, and was on sick leave from Congress for several months.

[30] The change in opponents was a mixed blessing for Douglas; it removed the incumbent from the field, but deprived her of the endorsement of the Daily News—one of the few big city papers to consistently support her.

In a Daily News column, Boddy wrote that Douglas was part of "a small minority of red hots" which proposed to use the election to "establish a beachhead on which to launch a Communist attack on the United States".

Douglas leased the craft from a helicopter company in Palo Alto owned by Republican supporters, who hoped her influence would lead to a defense contract.

[45] He considered his party's prospects in the House to be bleak, absent a strong Republican trend, and wrote "I seriously doubt if we can ever work our way back in power.

Actually, in my mind, I do not see any great gain in remaining a member of the House, even from a relatively good District, if it means we would be simply a vocal but ineffective minority.

[52] On January 21, 1950, the jury found Hiss guilty, and Nixon received hundreds of congratulatory messages, including one from the only living former president, Herbert Hoover.

[57] Nixon was opposed for the Republican nomination only by cross-filing Democrats and by two fringe candidates: Ulysses Grant Bixby Meyer, a consulting psychologist for a dating service,[56] and former judge and law professor Albert Levitt, who opposed "the political theories and activities of national and international Communism, Fascism, and Vaticanism" and was unhappy that the press was paying virtually no attention to his campaign.

The first meeting took place at the Commonwealth Club[e] in San Francisco, where Nixon waved a check for $100 that his campaign had received from "Eleanor Roosevelt", with an accompanying letter, "I wish it could be ten times more.

[50] The rift in the Democratic party caused by the primary was slow to heal; Boddy's supporters were reluctant to join Douglas's campaign, even with President Truman's encouragement.

[64] When the Korean War broke out in late June, Douglas and her aides feared being put on the defensive by Nixon on the subject of communism, and sought to preempt his attack.

"[71] Chotiner stated 20 years later that Marcantonio suggested the comparison of voting records, as he disliked Douglas for failing to support his beliefs fully.

[75] In a radio broadcast soon after the veto override, Douglas announced that she stood with the President, Attorney General J. Howard McGrath and FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover in their fight against communism.

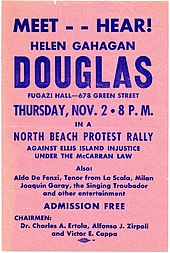

[76] On September 10, Eleanor Roosevelt, the late president's widow and the gubernatorial candidate's mother, arrived in California for a quick campaign swing to support her son and Douglas before she had to return to New York as a delegate to the United Nations.

[77] At a Democratic rally featuring Mrs. Roosevelt the next day in Long Beach, Nixon workers first handed out a flyer headed "Douglas–Marcantonio Voting Record", printed with dark ink on pink paper.

[78] Chotiner later stated that the color choice was made at the print shop when campaign officials approved the final copy, and "for some reason or other it just seemed to appeal to us for the moment".

[85] He also declined Douglas's pleas for a letter of support (privately calling her "one of the worst nuisances"), and even refused to allow her to be photographed with him at a signing ceremony for a water bill which would benefit California.

[86] When Truman flew to Wake Island in early October to confer with General Douglas MacArthur regarding the Korean situation, he returned via San Francisco, but told the press he had no political appointments scheduled.

[87] Attorney General McGrath also came to California to campaign for the Democrats,[88] and freshman Senator Hubert Humphrey of Minnesota tirelessly worked the San Joaquin Valley, talking to farmers and workers.

Supervisor John Anson Ford of Los Angeles County chalked up the result to Nixon's skill as a speaker and a lack of objective reporting by the press.

Gellman, in his later book, conceded that Nixon's officially reported amount of $4,209 was understated, but indicated that campaign finance law at that time was filled with loopholes, and few if any candidates admitted to their full spending.