United States antitrust law

[5] Surveys of American Economic Association members since the 1970s have shown that professional economists generally agree with the statement: "Antitrust laws should be enforced vigorously.

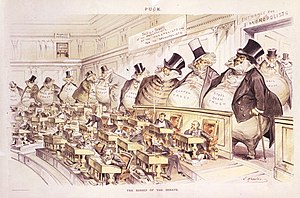

The term "antitrust" came from late 19th-century American industrialists' practice of using trusts—legal arrangements where one is given ownership of property to hold solely for another's benefit—to consolidate separate companies into large conglomerates.

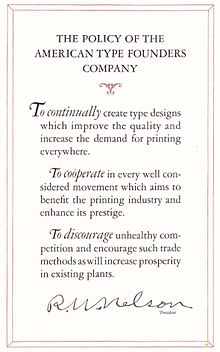

[16] With little interest in enforcing the Sherman Act and courts interpreting it relatively narrowly, a wave of large industrial mergers swept the United States in the late 1890s and early 1900s.

[16] Many observers thought the Supreme Court's decision in Standard Oil represented an effort by conservative federal judges to "soften" the Sherman Act and narrow its scope.

[21] At the urging of economists such as Frank Knight and Henry C. Simons, President Franklin D. Roosevelt's economic advisors began persuading him that free market competition was the key to recovery from the Great Depression.

[23] For example, in its 1962 decision Brown Shoe Co. v. United States,[25] the Supreme Court ruled that a proposed merger was illegal even though the resulting company would have controlled only five percent of the relevant market.

[23] In a now-famous line from his dissent in the 1966 decision United States v. Von's Grocery Co., Supreme Court justice Potter Stewart remarked: "The sole consistency that I can find [in U.S. merger law] is that in litigation under [the Clayton Act], the Government always wins.

"[26] The "structuralist" interpretation of U.S. antitrust law began losing favor in the early 1970s in the face of harsh criticism by economists and legal scholars from the University of Chicago.

Newer Chicago economists like Aaron Director argued that there were economic efficiency explanations for some practices that had been condemned under the structuralist interpretation of the Sherman and Clayton Acts.

[30] Judges increasingly accepted their ideas from the mid-1970s on, motivated in part by the United States' declining economic dominance amidst the 1973–1975 recession and rising competition from East Asian and European countries.

It reflects the view that each business has a duty to act independently on the market, and so earn its profits solely by providing better priced and quality products than its competitors.

In Copperweld Corp. v. Independence Tube Corp.[39] it was held an agreement between a parent company and a wholly owned subsidiary could not be subject to antitrust law, because the decision took place within a single economic entity.

Second, because the law does not seek to prohibit every kind of agreement that hinders freedom of contract, it developed a "rule of reason" where a practice might restrict trade in a way that is seen as positive or beneficial for consumers or society.

Third, significant problems of proof and identification of wrongdoing arise where businesses make no overt contact, or simply share information, but appear to act in concert.

Fourth, vertical agreements between a business and a supplier or purchaser "up" or "downstream" raise concerns about the exercise of market power, however they are generally subject to a more relaxed standard under the "rule of reason".

In the first case, United States v. Trans-Missouri Freight Association,[46] the Supreme Court found that railroad companies had acted unlawfully by setting up an organisation to fix transport prices.

[47] The Chicago Board of Trade had a rule that commodities traders were not allowed to privately agree to sell or buy after the market's closing time (and then finalise the deals when it opened the next day).

Judicial remedies can force large organizations to be broken up, subject them to positive obligations, impose massive penalties, and/or sentence implicated employees to jail.

[50] Historically, where the ability of judicial remedies to combat market power have ended, the legislature of states or the Federal government have still intervened by taking public ownership of an enterprise, or subjecting the industry to sector specific regulation (frequently done, for example, in the cases water, education, energy or health care).

Antitrust laws do not apply to, or are modified in, several specific categories of enterprise (including sports, media, utilities, health care, insurance, banks, and financial markets) and for several kinds of actor (such as employees or consumers taking collective action).

Public enforcement of antitrust laws is seen as important, given the cost, complexity and daunting task for private parties to bring litigation, particularly against large corporations.

[69] Despite considerable effort by the Clinton administration, the Federal government attempted to extend antitrust cooperation with other countries for mutual detection, prosecution and enforcement.

By offering potential litigants the prospect of a recovery in three times the amount of their damages, Congress encouraged these persons to serve as "private attorneys general".The Supreme Court calls the Sherman Antitrust Act a "charter of freedom", designed to protect free enterprise in America.

[76] One view of the statutory purpose, urged for example by Justice Douglas, was that the goal was not only to protect consumers, but at least as importantly to prohibit the use of power to control the marketplace.

It should be scattered into many hands so that the fortunes of the people will not be dependent on the whim or caprice, the political prejudices, the emotional stability of a few self-appointed men ... That is the philosophy and the command of the Sherman Act.

It is founded on a theory of hostility to the concentration in private hands of power so great that only a government of the people should have it.Contrary to this are efficiency arguments that antitrust legislation should be changed to primarily benefit consumers, and have no other purpose.

Free market economist Milton Friedman states that he initially agreed with the underlying principles of antitrust laws (breaking up monopolies and oligopolies and promoting more competition), but that he came to the conclusion that they do more harm than good.

The courts have long paid lip service to the distinction that economists make between competition—a set of economic conditions—and existing competitors, though it is hard to see how much difference that has made in judicial decisions.

[78]Alan Greenspan argues that the very existence of antitrust laws discourages businessmen from some activities that might be socially useful out of fear that their business actions will be determined illegal and dismantled by government.

[4] Thomas DiLorenzo, an adherent of the Austrian School of economics, found that the "trusts" of the late 19th century were dropping their prices faster than the rest of the economy, and he holds that they were not monopolists at all.