Universal health care

[1] Some universal healthcare systems are government-funded, while others are based on a requirement that all citizens purchase private health insurance.

[3] One of the goals with universal healthcare is to create a system of protection which provides equality of opportunity for people to enjoy the highest possible level of health.

[5] As part of Sustainable Development Goals, United Nations member states have agreed to work toward worldwide universal health coverage by 2030.

[6][better source needed] Therefore, the inclusion of the universal health coverage (UHC) within the SDGs targets can be related to the reiterated endorsements operated by the WHO.

Following the Russian Revolution of 1917, a fully public and centralized health care system was established in Soviet Russia in 1920.

Universal health care was next introduced in the Nordic countries of Sweden (1955),[16] Iceland (1956),[17] Norway (1956),[18] Denmark (1961)[19] and Finland (1964).

[citation needed] From the 1970s to the 2000s, Western European countries began introducing universal coverage, most of them building upon previous health insurance programs to cover the whole population.

[26][23] In addition, universal health coverage was introduced in some Asian countries, including Malaysia (1980s),[27] South Korea (1989), Taiwan (1995), Singapore (1993), Israel (1995) and Thailand (2001).

[33] A 2012 study examined progress being made by these countries, focusing on nine in particular: Ghana, Rwanda, Nigeria, Mali, Kenya, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam.

The only forms of government-provided healthcare available are Medicare (for elderly patients above age 65 as well as people with disabilities), Medicaid (for low-income people),[36][37] the Military Health System (active, reserve, and retired military personnel and dependants), and the Indian Health Service (members of federally recognized Native American tribes).

[39] Most universal health care systems are funded primarily by tax revenue (as in Portugal,[39] India, Spain, Denmark and Sweden).

Some nations, such as Germany, France,[40] and Japan,[41] employ a multi-payer system in which health care is funded by private and public contributions.

In this way, sickness funds compete on price and there is no advantage in eliminating people with higher risks because they are compensated for by means of risk-adjusted capitation payments.

[45] The Republic of Ireland at one time had a "community rating" system by VHI, effectively a single-payer or common risk pool.

The government later reintroduced community rating by a pooling arrangement and at least one main major insurance company, BUPA, withdrew from the Irish market.

[citation needed] In Poland, people are obliged to pay a percentage of the average monthly wage to the state, even if they are covered by private insurance.

[citation needed] In a social health insurance system, contributions from workers, the self-employed, enterprises and governments are pooled into single or multiple funds on a compulsory basis.

Social health insurance is used in a number of Western European countries and increasingly in Eastern Europe as well as in Israel and Japan.

The Planning Commission of India has also suggested that the country should embrace insurance to achieve universal health coverage.

[56] Individual members of a specific community pay to a collective health fund which they can draw from when they need medical care.

Challenges includes inequitable access by the poorest[57] that health service utilization of members generally increase after enrollment.

Others have a much more pluralistic delivery system, based on obligatory health with contributory insurance rates related to salaries or income and usually funded by employers and beneficiaries jointly.

The common denominator for all such programs is some form of government action aimed at extending access to health care as widely as possible and setting minimum standards.

Additionally, in the year 2019, it was found that 2 billion people experienced financial difficulties due to health expenses, with ongoing, significant disparities in coverage.

These measures aim to increase health service coverage by an additional 477 million individuals by the year 2023 and to continue progress towards covering an extra billion people by the 2030 deadline.

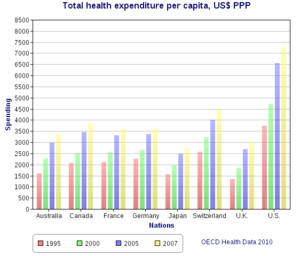

[65] Relatedly, some also argue that universal health care can be extremely expensive for governments to maintain, leading to higher taxes and potential strain on public finances, such as those in the Nordic countries, Australia, and New Zealand.

Also, they argue it represents unnecessary government overreach into the lives of American citizens and employers as it denies them individual choice.

[5] According to a 2020 study published in The Lancet, the proposed Medicare for All Act would save 68,000 lives and $450 billion in national healthcare expenditure annually.

[67] A 2022 study published in the PNAS found that a single-payer universal healthcare system would have saved 212,000 lives and averted over $100 billion in medical costs during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States in 2020 alone.