University of Minnesota Messenia Expedition

In the early 1950s, McDonald, soon joined by Richard Hope Simpson, carried out field surveys to match the toponyms given in the Linear B tablets from the Palace of Nestor at Pylos to then-undiscovered archaeological sites in Messenia.

[3] Kourouniotis had died in 1945, leaving Blegen in sole charge of the excavations: his successor at Archaeological Service, Spyridon Marinatos, focused his efforts primarily on fieldwork in the wider Messenia region.

[5] On May 19 1953, the British scholar Michael Ventris wrote to Blegen, offering a transcription and translation of the Linear B tablet PY Ta 641 found at Pylos the previous year.

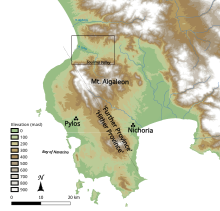

In 1935, the German archaeologist Georg Karo had been able to list only twenty-two plausibly-dated Mycenaean sites,[10] most of which were in turn derived from the survey conducted by the Swedish Natan Valmin [Wikidata], who had focused his efforts on the Soulima Valley in the north of the region.

Indeed, McDonald's later collaborator, Richard Hope Simpson, would publish several works in the same methodological vein, including his Ph.D. thesis and his co-authored 1970 volume The Catalogue of the Ships in Homer's Iliad, both of which attempted to find the archaeological analogues of the toponyms used in the so-called "Catalogue of Ships" in the second book of the Iliad,[16][17] and the publication of the UMME's findings would include the Trojan War as an historical event on its chronological chart.

[13] McDonald and his collaborators largely looked for material dated to the LH IIIB period (c. 1300 – c. 1180 BCE[20]), contemporary with the destruction of the palace at Pylos and the Linear B tablets discovered there.

[21][13] McDonald's first surveys took place over two weeks in 1953, covering an area 5 to 10 kilometres (3.1 to 6.2 mi) in radius around the site of the Palace of Nestor, accompanied by Charalambos Christophilopoulos, a Messenian who had studied archaeology under Kourouniotis.

[22] In other respects, McDonald experienced logistical and financial difficulties, later writing of his frustrations from having "practically no assured funding, and collegial attitudes ranging from cooperation to apathy to obstructionism.

These included large-scale, extensive survey (what McDonald called "regional exploration"),[24] initially conducted by using a Land Rover to drive around Messenia and coming across sites by happenstance.

[26] The survey's approach would later be referred to as 'the Hope Simpson method',[21] a label which McDonald resisted, writing in retrospect that "field strategies were not imposed by one collaborator but were gradually evolved by joint experience and discussion".

[21]An early indicator of the project's diachronic nature was the presence throughout the 1959 season of Peter Topping, director of the Gennadeion Library in Athens, who was researching the medieval habitation of Messenia.

[18] The later project's interdisciplinary nature was also foreshadowed by the two weeks in which Diomedes Charalambous, a geologist from the University of Athens, took part in the expedition, using an auger to uncover evidence of coastline changes since the Bronze Age.

[27][18] McDonald and Hope Simpson were joined on this expedition by three members of the University of Minnesota faculty: Jesse Fant, a civil engineer; Herbert E. Wright, a geologist; and Fred Lukermann, a geographer.

[31] The project secured the assistance of the Royal Hellenic Air Force to create aerial photographs of the region of Messenia, which were then interpreted by Fant (and later William Loy, who joined the project as a geographer and cartographer in 1965,[18]) to identify potential ancient sites: McDonald and Hope Simpson later estimated that this allowed them to reduce their false positive rate for site identification below 50%, in contrast to over 90% from surface survey alone.

[37] Reviewing the work in the American Journal of Archaeology, L. Vance Watrous [Wikidata] credited it, along with Blegen's volumes from the Pylos excavations, as having established Messenia as "the best-documented region of prehistoric Greece",[38] an estimation echoed by the Mycenaean scholar Sterling Dow.

[71] The UMME's approach was later criticised for its reliance on aerial photography and the investigators' intuition to identify areas for survey, which led to uneven coverage and a tendency to miss smaller sites, particularly those whose location did not conform to the surveyors' expectations,[72] but also described as "a prodigious influence on the development of archaeology in Greece", which "permitted for the first time the systematic examination of Mycenaean geography.

[76] However, the expedition also observed a large amount of continuity in site use and habitation on either side of the LH IIIB/IIIC divide, which suggested to McDonald and Hope Simpson that any collapse in the society of Mycenaean Messenia could not have been total.

"[78] The project's interest in zooarchaeology and the recovery of animal bones made Nichoria into an important site for the study of diet in Mycenaean and Iron Age Greece.

[79][80] Initial examination by the expedition's animal-bone specialists, Robert Sloan and Mary Ann Duncan, suggested that the primary meat consumed at Nichoria during the Mycenaean period came from goats, followed by sheep, pigs and cattle.

Under this hypothesis, large, permanent, archaeologically-visible settlements were abandoned in favour of transient pastoralism,[83] which Snodgrass justified by the apparent rise in the proportion of cattle reared and consumed at Nichoria during this period.

[84] However, later studies by Elizabeth Mancz, who completed a PhD on the material in the 1980s, and Flint Dibble, who reviewed and reassessed the bones in the early 21st century, questioned the underlying data.

Both Mancz and Dibble suggested that the apparent increase in the ratio of cattle bones is best explained by taphonomic processes, specifically chemical and attritional weathering, which had a disproportionate effect on later chronological layers (which lay closer to the surface) and the smaller bones of goats and sheep, and so artificially inflated the apparent proportion of cattle in the Early Iron Age samples vis-à-vis those from the Bronze Age.