Upton Sinclair

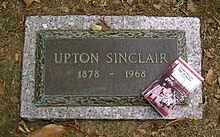

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American author, muckraker, and political activist, and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California.

"[4] He used this line in speeches and the book about his campaign for governor as a way to explain why the editors and publishers of the major newspapers in California would not treat seriously his proposals for old age pensions and other progressive reforms.

Writing during the Progressive Era, Sinclair describes the world of the industrialized United States from both the working man's and the industrialist's points of view.

The Flivver King describes the rise of Henry Ford, his "wage reform" and his company's Sociological Department, to his decline into antisemitism as publisher of The Dearborn Independent.

[10] After leaving Columbia without a degree, he wrote four books in the next four years; they were commercially unsuccessful though critically well-received: King Midas (1901), Prince Hagen (1902), The Journal of Arthur Stirling (1903), and a Civil War novel, Manassas (1904).

[19][20] William McDougall read the book and wrote an introduction to it, which led him to establish the parapsychology department at Duke University.

Wanting to pursue politics, he twice ran unsuccessfully for the United States Congress on the Socialist Party ticket: in 1920 for the House of Representatives and in 1922 for the Senate.

For instance, in 1923, to support the challenged free speech rights of Industrial Workers of the World, Sinclair spoke at a rally during the San Pedro Maritime Strike, in a neighborhood now known as Liberty Hill.

They pressured their employees to assist and vote for Merriam's campaign, and made false propaganda films attacking Sinclair, giving him no opportunity to respond.

[28] The negative campaign tactics used against Sinclair are briefly depicted in the 2020 American biographical drama film Mank.

[30] Sinclair's plan to end poverty quickly became a controversial issue under the pressure of numerous migrants to California fleeing the Dust Bowl.

Science-fiction author Robert A. Heinlein was deeply involved in Sinclair's campaign, although he attempted to move away from the stance later in his life.

In 1935, he published I, Candidate for Governor: And How I Got Licked, in which he described the techniques employed by Merriam's supporters, including the then popular Aimee Semple McPherson, who vehemently opposed socialism and what she perceived as Sinclair's modernism.

[38]In April 1900, Sinclair went to Lake Massawippi in Quebec to work on a novel, renting a small cabin for three months and then moving to a farmhouse where he was reintroduced to his future first wife, Meta Fuller (1880–1964).

A childhood friend descended from one of the First Families of Virginia,[6] she was three years younger than he and aspired to be more than a housewife, so Sinclair instructed her in what to read and learn.

[43] His wife later had a love affair with John Armistead Collier, a theology student from Memphis; they had a son together named Ben.

[45] In 1911, Sinclair was arrested for playing tennis on the Sabbath and spent eighteen hours in the New Castle County prison in lieu of paying a fine.

[46][47] Earlier in 1911, Sinclair invited Harry Kemp, the "Vagabond Poet", to camp on the couple's land in Arden.

[55] They moved to Buckeye, Arizona, before returning east to Bound Brook, New Jersey, where Sinclair died in a nursing home on November 25, 1968, a year after his wife.

[40] He is buried next to Willis in Rock Creek Cemetery in Washington, D.C. Sinclair devoted his writing career to documenting and criticizing the social and economic conditions of the early 20th century in both fiction and nonfiction.

His novel based on the meatpacking industry in Chicago, The Jungle, was first published in serial form in the socialist newspaper Appeal to Reason, from February 25, 1905, to November 4, 1905.

[56] Sinclair had spent about six months investigating the Chicago meatpacking industry for Appeal to Reason, the work which inspired his novel.

He intended to "set forth the breaking of human hearts by a system which exploits the labor of men and women for profit".

[7] The novel featured Jurgis Rudkus, a Lithuanian immigrant who works in a meat factory in Chicago, his teenage wife Ona Lukoszaite, and their extended family.

[59] At the time, President Theodore Roosevelt characterized Sinclair as a "crackpot",[60] writing to William Allen White, "I have an utter contempt for him.

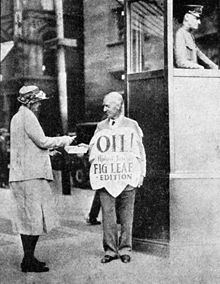

In The Brass Check (1919), Sinclair made a systematic and incriminating critique of the severe limitations of the "free press" in the United States.

This bias, Sinclair felt, had profound implications for American democracy: The social body to which we belong is at this moment passing through one of the greatest crises of its history .... What if the nerves upon which we depend for knowledge of this social body should give us false reports of its condition?This was a pamphlet[69] he published in 1934 as a preface to running for office in the state of California.

The son of an American arms manufacturer, Budd is portrayed as holding in the confidence of world leaders, and not simply witnessing events, but often propelling them.

As a sophisticated socialite who mingles easily with people from all cultures and socioeconomic classes, Budd has been characterized as the antithesis of the stereotyped "Ugly American".

[77][78] In the last years of his life, Sinclair strictly ate three meals a day consisting only of brown rice, fresh fruit and celery, topped with powdered milk and salt, and pineapple juice to drink.