Principles of Islamic jurisprudence

[1] Traditional theory of Islamic jurisprudence elaborates how the scriptures (Quran and hadith) should be interpreted from the standpoint of linguistics and rhetoric.

[2] In addition to the Quran and hadith, the classical theory of Sunni jurisprudence recognizes secondary sources of law: juristic consensus (ijmaʿ) and analogical reasoning (qiyas).

[2] The theory of Twelver Shia jurisprudence parallels that of Sunni schools with some differences, such as recognition of reason (ʿaql) as a source of law in place of qiyās and extension of the notions of hadith and sunnah to include traditions of the imams.

[5] However, they believed that use of reason alone is insufficient to distinguish right from wrong, and that rational argumentation must draw its content from the body of transcendental knowledge revealed in the Quran and through the sunnah of Muhammad.

[6] Classical jurists held its textual integrity to be beyond doubt on account of it having been handed down by many people in each generation, which is known as "recurrence" or "concurrent transmission" (tawātur).

[7][6] Early Islamic scholars developed a methodology for evaluating their authenticity by assessing trustworthiness of the individuals listed in their transmission chains.

[6] These criteria narrowed down the vast corpus of prophetic traditions to several thousand "sound" hadiths, which were collected in several canonical compilations.

[6] Disagreements on the relative merits and interpretation of the textual sources allowed legal scholars considerable leeway in formulating alternative rulings.

[11] The classical process of ijtihād combined these generally recognized principles with other methods, which were not adopted by all legal schools, such as istiḥsān (juristic preference), istiṣlāḥ (consideration of public interest) and istiṣḥāb (presumption of continuity).

[12] By the beginning of the 10th century, development of Sunni jurisprudence prompted leading jurists to state that the main legal questions had been addressed and the scope of ijtihad was gradually restricted.

[12][13] From the 18th century on, leading Muslim reformers began calling for abandonment of taqlid and renewed emphasis on ijtihad, which they saw as a return to the vitality of early Islamic jurisprudence.

[7] Maqāṣid (aims or purposes) of sharia and maṣlaḥa (welfare or public interest) are two related classical doctrines which have come to play an increasingly prominent role in modern times.

[15][16][17] They were first clearly articulated by al-Ghazali (d. 1111 C.E/ 505 A.H), who argued that maslaha was God's general purpose in revealing the divine law, and that its specific aim was preservation of five essentials of human well-being: religion, life, intellect, offspring, and property.

[18] Although most classical-era jurists recognized maslaha and maqāsid as important legal principles, they held different views regarding the role they should play in Islamic law.

[15][20] While the latter view was held by a minority of classical jurists, in modern times it came to be championed in different forms by prominent scholars who sought to adapt Islamic law to changing social conditions by drawing on the intellectual heritage of traditional jurisprudence.

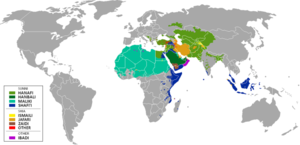

[21] The Hanbali school, with its particularly strict adherence to the Quran and hadith, has inspired conservative currents of direct scriptural interpretation by the Salafi and Wahhabi movements.

[29] This division into four sources is most often attributed to later jurists upon whose work most Sunni jurisprudence has been modeled such as Baqillani and Abd al-Jabbar ibn Ahmad,[30] of the Ash'arite and Mu'tazilite schools respectively.

[1][39] Shi'ites may differ in the exact application of principles depending on whether they follow the Ja'fari, Ismaili or Zaidi subdivisions of Shi'ism.

Javadi Amoli wrote about source of revelation in Shiism: In doubtful cases the law is often derived not from substantive principles induced from existing rules, but from procedural presumptions (usul 'amaliyyah) concerning factual probability.

[41] The analysis of probability forms a large part of the Shiite science of usul al-fiqh, and was developed by Muhammad Baqir Behbahani (1706–1792) and Shaykh Murtada al-Ansari (died 1864).

The only primary text on Shi'ite principles of jurisprudence in English is the translation of Muhammad Baqir as-Sadr's Durus fi 'Ilm al-'Usul.