Utah Beach

While improvements to fortifications had been undertaken under the leadership of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel beginning in October 1943, the troops assigned to defend the area were mostly poorly equipped non-German conscripts.

At the close of D-Day, Allied forces had only captured about half of the planned area and contingents of German defenders remained, but the beachhead was secure.

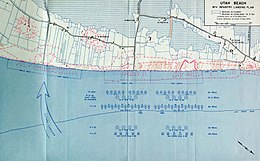

[14] The coastline of Normandy was divided into seventeen sectors, with codenames using a spelling alphabet—from Able, west of Omaha, to Roger on the east flank of Sword.

[18] The need to acquire or produce extra landing craft and troop carrier aircraft for the expanded operation meant that the invasion had to be delayed to June.

[20] More than 600 Douglas C-47 Skytrain transport aircraft and their crews took a circuitous route to England in early 1944 from Baer Field, Indiana, bringing the number of available troop carrier planes to over a thousand.

[25] The second wave, scheduled for 06:35, consisted of 32 LCVPs carrying four more companies of 8th Infantry, as well as combat engineers and naval demolition teams that were to clear the beach of obstacles.

It was to be followed at 06:37 by the fourth wave, which had eight Landing Craft Mechanized (LCM) and three LCVPs with detachments of the 237th and 299th Combat Engineer Battalions, assigned to clear the beach between the high and low water marks.

[26] Troops involved in Operation Overlord, including members of the 4th Division scheduled to land at Utah, left their barracks in the second half of May and proceeded to their coastal marshalling points.

[29][30][31] The ships met at a rendezvous point (nicknamed "Piccadilly Circus") southeast of the Isle of Wight to assemble into convoys to cross the Channel.

[33] Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt, overall commander on the Western Front, reported to Hitler in October 1943 regarding the weak defenses in France.

This led to the appointment of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel to oversee the construction of enhanced fortifications along the Atlantic Wall, with special emphasis on the most likely invasion front, which stretched from the Netherlands to Cherbourg.

In addition to concrete gun emplacements at strategic points along the coast, he ordered wooden stakes, metal tripods, mines, and large anti-tank obstacles to be placed on the beach to delay the approach of landing craft and impede the movement of tanks.

[36] Expecting the Allies to land at high tide so that the infantry would spend less time exposed on the beach, he ordered many of these obstacles to be placed at the high-tide mark.

[39] Defense of this sector of eastern coast of the Cotentin Peninsula was assigned to Generalleutnant Karl-Wilhelm von Schlieben and his 709th Static Infantry Division.

[42] Tangles of barbed wire, booby traps, and the removal of ground cover made both the beach and the terrain around the strongpoints hazardous for infantry.

[48] Generalleutnant Wilhelm Falley, commander of 91st Infantry Division, was trying to return to his headquarters near Picauville from war games at Rennes when he was killed by a paratrooper patrol.

[49] Two hours before the main invasion force landed, a raiding party of 132 members of 4th Cavalry Regiment swam ashore at 04:30 at Îles Saint-Marcouf, thought to be a German observation post.

[53] USS Corry, a destroyer in the bombardment group, sank after it struck a mine while evading fire from the Marcouf battery under the command of Oberleutnant zur See Walter Ohmsen.

[54] Coastal air bombardment was undertaken in the twenty minutes immediately prior to the landing by approximately 300 Martin B-26 Marauders of the IX Bomber Command.

[61] Four tanks of Company A and their personnel were lost when their LCT hit a mine about 3 miles (4.8 km) south of Iles St. Marcouf and was destroyed, but the remaining 28 arrived intact.

[63] They were followed at 06:37 by the fourth wave, which had eight LCMs and three LCVPs with detachments of the 237th and 299th Combat Engineer Battalions, assigned to clear the beach between the high and low water marks.

[67] Removal of mines and obstacles from the beach, a job that had to be performed quickly before the tide came in at 10:30, was the assignment of 237th and 299th Combat Engineer Battalions and the eight dozer tanks.

[70] The next move for the 4th Division was to begin movement down the three causeways through the flooded farmland behind the beach to link up with the 101st Airborne, who had dropped behind enemy lines before dawn.

[75] The Germans had blown a small bridge over a culvert, and movement was delayed while engineers made a repair and cleared two inoperable tanks from the road.

[79] By evening they had combined with 12th Infantry, who had traveled directly across the flooded fields to a position far short of their target for the day, to form a defensive perimeter on the northern end of the beachhead.

[4][80] On the southern end of the beachhead, about 3,000 men of the 6th Fallschirmjäger Regiment moved into position near Saint-Côme-du-Mont, preventing the 501st Parachute Infantry from advancing any further on D-Day.

[81] In the center, the 82nd Airborne were able to consolidate their position at Sainte-Mère-Église in part due to the work of First Lieutenant Turner Turnbull and a squad of 43 men, who held off for more than two hours a far larger enemy force that was attempting to retake the crossroads from the north.

The original plan for the 90th had been that they should push north toward the port of Cherbourg, but Collins changed their assignment: they were to cut across the Cotentin Peninsula, isolating the German forces therein and preventing reinforcements from entering the area.

[89] Their poor performance led to their being replaced by the more experienced 82nd Airborne and 9th Infantry Division, who reached the west coast of the Cotentin on June 17, cutting off Cherbourg.

[92][93] Within two hours of landing, the 82nd Airborne captured the important crossroads at Sainte-Mère-Église, but they failed to neutralize the line of defenses along the Merderet on D-Day as planned.