Bell Boeing V-22 Osprey

The failure of Operation Eagle Claw in 1980 during the Iran hostage crisis underscored that there were military roles for which neither conventional helicopters nor fixed-wing transport aircraft were well-suited.

[3] The V-22 first flew in 1989 and began flight testing and design alterations; the complexity and difficulties of being the first tiltrotor for military service led to many years of development.

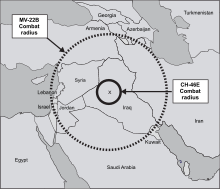

Since entering service with the Marine Corps and Air Force, the Osprey has been deployed in transportation and medevac operations over Iraq, Afghanistan, Libya, and Kuwait.

The failure of Operation Eagle Claw, the Iran hostage rescue mission, in 1980 demonstrated to the U.S. military a need[4][5] for "a new type of aircraft, that could not only take off and land vertically but also could carry combat troops, and do so at speed.

[12] The Office of the Secretary of Defense and Navy administration opposed the tiltrotor project, but pressure from Congress had a significant effect on the program's development.

[18][19] The JVX aircraft was designated V-22 Osprey on 15 January 1985; by that March, the first six prototypes were being produced, and Boeing Vertol was expanded to handle the workload.

[30] As development cost projections greatly increased in 1988, Defense Secretary Dick Cheney tried to defund it from 1989 to 1992, but was overruled by Congress,[14][31] which provided unrequested program funding.

[52] Development was protracted and controversial, partly because of large cost increases,[53] some of which were caused by a requirement to fold wings and rotors to fit aboard ships.

[56]In 2001, Lieutenant Colonel Odin Leberman, commander of the V-22 squadron at Marine Corps Air Station New River, was relieved of duty after allegations that he instructed his unit to falsify maintenance records to make it appear more reliable.

[70] From 2009 to 2014, readiness rates rose 25% to the "high 80s", while cost per flight hour had dropped 20% to $9,520 through a rigorous maintenance improvement program that focused on diagnosing problems before failures occur.

[95] Manufacturing robots have replaced older automated machines for increased accuracy and efficiency; large parts are held in place by suction cups and measured electronically.

[96][97] In March 2014, Air Force Special Operations Command issued a Combat Mission Need Statement for armor to protect V-22 passengers.

Costing $270,000, the ABSS consists of 66 plates fitting along interior bulkheads and deck, adding 800 lb (360 kg) to the aircraft's weight, affecting payload and range.

[111] Because of the requirement for folding rotors, their 38-foot (12 m) diameter is 5 feet (1.5 m) less than would be optimal for an aircraft of this size to conduct vertical takeoff, resulting in high disk loading.

This fixed wing flight is higher than typical helicopter missions allowing longer range line-of-sight communications for improved command and control.

[130][131] With the nacelles pointing straight up in conversion mode at 90° the flight computers command it to fly like a helicopter, cyclic forces being applied to a conventional swashplate at the rotor hub.

[108][76] As of April 2021[update] the US military does not track whether fixed-wing or helicopter pilots transition more easily to the V-22, according to USMC Colonel Matthew Kelly, V-22 project manager.

[139] The IDWS was installed on half of the V-22s deployed to Afghanistan in 2009;[138] it found limited use because of its 800 lb (360 kg) weight and restrictive rules of engagement.

[141] In 2014, the USMC studied new weapons with "all-axis, stand-off, and precision capabilities", akin to the AGM-114 Hellfire, AGM-176 Griffin, Joint Air-to-Ground Missile, and GBU-53/B SDB II.

[142] In November 2014, Bell Boeing conducted self-funded weapons tests, equipping a V-22 with a pylon on the front fuselage and replacing the AN/AAQ-27A EO camera with an L-3 Wescam MX-15 sensor/laser designator.

The USMC and USAF sought a traversable nose-mounted weapon connected to a helmet-mounted sight; recoil complicated integrating a forward-facing gun.

In December 2005, Lieutenant General James Amos, commander of II Marine Expeditionary Force, accepted delivery of the first batch of MV-22s.

[167][168] The report concluded: "deployments confirmed that the V-22's enhanced speed and range enable personnel and internal cargo to be transported faster and farther than is possible with the legacy helicopters".

[182] In 2013, following Typhoon Haiyan, 12 MV-22s of the 3rd Marine Expeditionary Brigade were deployed to the Philippines for disaster relief operations;[183] its abilities were described as "uniquely relevant", flying faster and with greater payloads while moving supplies throughout the island archipelago.

[192] In 2019, a plan was formulated for the USAF V-22 to use the AN/APQ-187 Silent Knight terrain avoidance radar, which was tested on the CV-22 at Eglin Air Force base by 2020.

[195] On 29 November 2023, a CV-22B assigned to the US Air Force's 353rd Special Operations Wing crashed into the East China Sea off Yakushima Island, Japan, killing all eight airmen aboard.

[236] Canada is thought to have considered the V-22 for the Fixed Wing Search and Rescue (FWSAR), but it was not entered as the overall goals prioritized conventional aircraft; that program was won by the C-295, a fixed-wing medium transport.

It was noted that the V-22 could provide a unique logistical support to the island chain nation, but the concerns about purchase and maintenance costs were an issue.

[245] As of 2017, Israel had frozen its evaluation of the V-22, "with a senior defence source indicating that the tiltrotor is unable to perform some missions currently conducted using its Sikorsky CH-53 transport helicopters.

[297] Data from Norton,[304] Boeing,[305] Bell Guide,[106] Naval Air Systems Command,[306] and USAF CV-22 fact sheet[252]General characteristics Performance Armament Avionics Related development Aircraft of comparable role, configuration, and era