Quark model

The quark model underlies "flavor SU(3)", or the Eightfold Way, the successful classification scheme organizing the large number of lighter hadrons that were being discovered starting in the 1950s and continuing through the 1960s.

It received experimental verification beginning in the late 1960s and is a valid and effective classification of them to date.

The model was independently proposed by physicists Murray Gell-Mann,[1] who dubbed them "quarks" in a concise paper, and George Zweig,[2][3] who suggested "aces" in a longer manuscript.

André Petermann also touched upon the central ideas from 1963 to 1965, without as much quantitative substantiation.

One set comes from the Poincaré symmetry—JPC, where J, P and C stand for the total angular momentum, P-symmetry, and C-symmetry, respectively.

The strong interactions binding the quarks together are insensitive to these quantum numbers, so variation of them leads to systematic mass and coupling relationships among the hadrons in the same flavor multiplet.

Each quark or antiquark obeys the Gell-Mann–Nishijima formula individually, so any additive assembly of them will as well.

Developing classification schemes for hadrons became a timely question after new experimental techniques uncovered so many of them that it became clear that they could not all be elementary.

and Enrico Fermi to advise his student Leon Lederman: "Young man, if I could remember the names of these particles, I would have been a botanist."

These new schemes earned Nobel prizes for experimental particle physicists, including Luis Alvarez, who was at the forefront of many of these developments.

Constructing hadrons as bound states of fewer constituents would thus organize the "zoo" at hand.

Several early proposals, such as the ones by Enrico Fermi and Chen-Ning Yang (1949), and the Sakata model (1956), ended up satisfactorily covering the mesons, but failed with baryons, and so were unable to explain all the data.

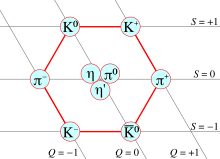

The hadrons were organized into SU(3) representation multiplets, octets and decuplets, of roughly the same mass, due to the strong interactions; and smaller mass differences linked to the flavor quantum numbers, invisible to the strong interactions.

After it was discovered in an experiment at Brookhaven National Laboratory, Gell-Mann received a Nobel Prize in Physics for his work on the Eightfold Way, in 1969.

Finally, in 1964, Gell-Mann and George Zweig, discerned independently what the Eightfold Way picture encodes: They posited three elementary fermionic constituents—the "up", "down", and "strange" quarks—which are unobserved, and possibly unobservable in a free form.

Simple pairwise or triplet combinations of these three constituents and their antiparticles underlie and elegantly encode the Eightfold Way classification, in an economical, tight structure, resulting in further simplicity.

Conversely, the quarks serve in the definition of quantum chromodynamics, the fundamental theory fully describing the strong interactions; and the Eightfold Way is now understood to be a consequence of the flavor symmetry structure of the lightest three of them.

However, the physical content of the full theory[clarification needed] includes consideration of the symmetry breaking induced by the quark mass differences, and considerations of mixing between various multiplets (such as the octet and the singlet).

Nevertheless, the mass splitting between the η and the η′ is larger than the quark model can accommodate, and this "η–η′ puzzle" has its origin in topological peculiarities of the strong interaction vacuum, such as instanton configurations.

If the quark–antiquark pair are in an orbital angular momentum L state, and have spin S, then If P = (−1)J, then it follows that S = 1, thus PC = 1.

The decuplet is symmetric in flavor, the singlet antisymmetric and the two octets have mixed symmetry.

The space and spin parts of the states are thereby fixed once the orbital angular momentum is given.

The 56 states with symmetric combination of spin and flavour decompose under flavor SU(3) into

Mixing of baryons, mass splittings within and between multiplets, and magnetic moments are some of the other quantities that the model predicts successfully.

A simpler approach is to consider the eight flavored quarks as eight separate, distinguishable, non-identical particles.

[6] Then, the proton wavefunction can be written in a simpler form: and the If quark–quark interactions are limited to two-body interactions, then all the successful quark model predictions, including sum rules for baryon masses and magnetic moments, can be derived.

Color quantum numbers are the characteristic charges of the strong force, and are completely uninvolved in electroweak interactions.

Oscar Greenberg noted this problem in 1964, suggesting that quarks should be para-fermions.

[7] Instead, six months later, Moo-Young Han and Yoichiro Nambu suggested the existence of a hidden degree of freedom, they labeled as the group SU(3)' (but later called 'color).

This led to three triplets of quarks whose wavefunction was anti-symmetric in the color degree of freedom.