Valentinian dynasty

The Valentinian dynasty also saw the reintroduction of Christianity after a brief period during which the emperor Julian attempted to reimpose traditional Roman religions, but tolerance and religious freedom persisted for some time in the west.

'companion'), often translated as count,[62] were high-ranking officials or ministers who enjoyed the trust and companionship of the emperor, and collectively were referred to as comitiva, the governing council of the empire, from which the term comitatus for the imperial court is derived.

[63] The fourth century historian Ammianus Marcellinus,[64] recounts that once Jovian's body was embalmed and dispatched to Constantinople, the legions continued on to Nicaea in Turkey, where military and civilian staff sought a new emperor.

[67][68] To avoid the instability caused by the deaths of his two predecessors, and rivalry between the armies, Valentinian (r. 364–375) acceded to the demands of his soldiers and ruled the western provinces while elevating his younger and relatively inexperienced brother Valens (b.

[87] The 5th-century Greek historian Socrates Scholasticus tells that while serving as in the protectores Valens refused pressure to offer sacrifice in ancient Roman religion during the reign of the pagan emperor Julian (r. 361–363).

[92] An opportunity to further weaken the Alamanni occurred in the summer of 368, when king Vithicabius was murdered in a coup, and Valentinian and his son Gratian crossed the Moenus (Main river) laying waste to their territories.

Lupicinus, then realising his management of the Danube crossing had been disastrously mismanaged decided on a full-scale attack on the Goths near Marcianopolis in Moesia Inferior (Bulgaria), and was promptly routed, leaving Thrace undefended from the north.

He sought help from his nephew Gratian, now the western emperor, and took his forces across to Europe in the spring of 377, pressing the Goths into the Haemus mountains and meeting the legions dispatched from Pannonia and Gaul at a place called ad Salices, near Marcianopolis.

On 1 November 365, while on his way to Lutetia (Paris), Valentinian learned of the appearance of the usurper Procopius in Constantinople,[68] but was unable to move against him, judging a simultaneous invasion of Gaul by Alamanni a greater threat to the empire.

In the spring of 365, sensing the unpopularity of Valens, who had succeeded Jovian in 364, he made plans for a possible coup, persuading some of the legions to recognise him during the emperor's absence in Antioch, directing military operations.

According to Ammianus Marcellinus, when Valens forces met the usurper's army at Mygdus[k] on the river Sangarius in Phrygia, Procopius denounced the Pannonian accession and persuaded the advancing legions to defect.

Although Procopius suffered a setback in the west, when Aequitius, magister militum per Illyricum, succeeded in blocking all the communicating passages between the eastern and western empires, in the east he rapidly consolidated his hold over Bithynia.

[74] Theodosius' first priority was to rebuild the depleted legions, with sweeping conscription laws, but to do so he needed to recruit large numbers of non-Romans, further changing an empire that was becoming increasingly diverse.

[113] After several more unsuccessful encounters with the Goths, he made peace, finally ending the Gothic war of 376–382, but in doing so settled large numbers of barbarians on the Danube in Lower Moesia, Thrace, Dacia Ripensis, and Macedonia.

[116][118] With the collapse of the Danube frontier[n] under the incursions of the Huns and Goths, Gratian moved his seat from Augusta Treverorum (Trier) to Mediolanum (Milan) in 381,[44] and was increasingly aligned with the city's bishop, Ambrose (374–397), and the Roman Senate, shifting the balance of power within the factions of the western empire.

[122] The body of Constantia, Gratian's first wife, who had died earlier that year, arrived in Constantinople on 12 September 383 and was buried in the complex of the Church of the Holy Apostles (Apostoleion) on 1 December, the resting place of a number of members of the imperial family, starting with Constantine in 337, under the direction of Theodosius, who had embarked on making the site a dynastic symbol.

[119] Under this agreement Maximus kept the western portion of the Empire including Britain, Spain and Gaul, while Valentinian ruled over Italy, Africa and Illyricum, allowing Theodosius to concentrate on his eastern problems and the threat to Thrace.

In the autumn of 384, the Senator Q Aurelius Symmachus, then prefect of Rome (Latin: praefectus urbi) pleaded with Valentinian for its return to the Curia Julia, but Ambrose succeeded in firmly rejecting such a suggestion.

[130][78] According to Ambrose's Sermon Against Auxentius and his 76th Epistle when the bishop was summoned to the court of Valentinian II and his mother Justina in 385, the Nicene Christians appeared en masse to support him, threatening the emperor's security and offering themselves to be martyred by the army.

[121] On Valentinian's restoration, Theodosius' clemency emboldened the supporters of the altar of Victory to once more travel to Milan to request its return, but their pleas were rejected and Symmachus exiled from Rome[126] (though eventually forgiven and given a consulship).

Simultaneously a series of revolts too place in Britain, raising usurpers, the last of which was Constantine, who crossed into Gaul in the spring of 407, taking command of the Roman forces there and advancing as far as the alps.

Constantine established himself in Arelate, (Arles, Provence) in the strategic province of Gallia Narbonensis, stretching from the alps in the east to the Pyrenees in the south, and thus guarding the entrances to both Italy and Spain.

[12] Although Placidia spent much of her early years in Milan, the continuing invasions of Visigoths led to the court moving to a more secure position further south at Ravenna in 402, but with frequent visits to Rome, where Stilicho and Serena also maintained a house.

[157] According to Orosius, Olympiodorus of Thebes, Philostorgius, Prosper of Aquitaine, the Chronica Gallica of 452, Hydatius, Marcellinus Comes, and Jordanes, they were married at Narbo (Narbonne) in January 414, where Athaulf had established his court on the Via Domitia in Gallia Narbonensis.

[173][170][157] She may have been banished by Honorius, with whom her relations were previously close, because according to Olympiodorus, Philostorgius, Prosper, and the Chronica Gallica of 452, gossip about the nature of their relationship that arose after Constantius's death caused them to quarrel.

[175] With a six year old titular emperor, the real power lay with, his mother, and the three major military commanders, though these were locked in struggles against each other, from which Flavius Aetius emerged as the sole survivor by 433, appointing himself patricius.

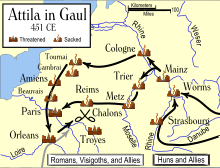

[180] Following a diplomatic offensive based on this, Attila marched westwards along the Danube in early 451, crossing the Rhine at Mogontiacum (Mainz) and ravaging Belgica and northern Gallia as far south as Cenabum (Orleans).

[184][185] On Petronius' death, his magister militum praesentalis (Master of Soldiers in the Presence) Avitus (r. 455–456), then in Gallia seeking the loyalty of the Visgoths, was proclaimed augustus in Arles on or about 10 July, traveling to Rome in September.

His attempts to improve Roman control in Gallia, by giving more influence to Gallo-Romans was not popular and by 456 was faced by open revolt and was deposed by his magister militum, Ricimer at the Battle of Placentia (Piacenza) in October.

By this time the effective empire had shrunk further considerably, and Orestes and Romulus Augustus faced a major threat from Odoacer, a barbarian soldier and leader of the foederati in Italy.