Valley of the Kings

The royal tombs are decorated with traditional scenes from Egyptian mythology and reveal clues to the period's funerary practices and afterlife beliefs.

This area has been a focus for Egyptologists and archaeological exploration since the end of the 18th century, and its tombs and burials continue to stimulate research and interest.

The Valley of the Kings garnered significant attention following the discovery of the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922,[10] and is one of the most famous archaeological sites in the world.

The sedimentary rock was originally deposited between 35 and 56 million years ago during a time when the Mediterranean Sea sometimes extended as far south as Aswan.

[14] The quality of the rock in the Valley is inconsistent, ranging from finely grained to coarse stone, the latter with the potential to be structurally unsound.

The occasional layer of shale also caused construction (and in modern times, conservation) difficulties, as this rock expands in the presence of water, forcing apart the stone surrounding it.

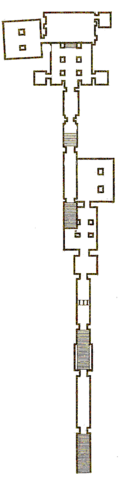

Some tombs were quarried out of existing limestone clefts, others behind slopes of scree, and some were at the edge of rock spurs created by ancient flood channels.

[15] The tomb of Ramesses II returned to an early style, with a bent axis, probably due to the quality of the rock being excavated (following the Esna shale).

[20] This was the area that was the subject of the Amarna Royal Tombs Project ground-scanning radar investigation, which showed several anomalies, one of which was proved to be KV63.

[22] It has a pyramid-shaped appearance, and it is probable that this echoed the pyramids of the Old Kingdom, more than a thousand years prior to the first royal burials carved here.

[25] While the iconic pyramid complex of the Giza Plateau have come to symbolize ancient Egypt, the majority of tombs were cut into rock.

Most pyramids and mastabas contain sections which were cut into ground level, and there are full rock-cut tombs in Egypt that date back to the Old Kingdom.

[26] After the defeat of the Hyksos and the reunification of Egypt under Ahmose I, the Theban rulers began to construct elaborate tombs that reflected their newfound power.

[27] The tombs of Ahmose I and his son Amenhotep I (their exact location remains unknown) were probably in the Seventeenth Dynasty necropolis of Dra' Abu el-Naga'.

[31] The area illustrates the changes in the study of ancient Egypt, starting as antiquity hunting, and ending as scientific excavation of the whole Theban Necropolis.

Jules Baillet has located over 2,100 Greek and Latin instances of graffiti, along with a smaller number in Phoenician, Cypriot, Lycian, Coptic, and other languages.

Early in the century, the area was visited by Giovanni Belzoni, working for Henry Salt, who discovered several tombs, including those of Ay in the West Valley (WV23) in 1816 and Seti I (KV17) the following year.

The decipherment of hieroglyphs, though still incomplete during Wilkinson's stay in the valley, enabled him to assemble a chronology of New Kingdom rulers based on the inscriptions in the tombs.

Auguste Mariette's Egyptian Antiquities Service started to explore the valley, first with Eugène Lefébure in 1883,[50] then Jules Baillet and Georges Bénédite in early 1888, and finally Victor Loret in 1898 to 1899.

Maspero appointed English archaeologist Howard Carter as the Chief Inspector of Upper Egypt, and the young man discovered several new tombs and explored several others, clearing KV42 and KV20.

"[54] After Davis's death early in 1915, Lord Carnarvon acquired the concession to excavate the valley, and he employed Howard Carter to explore it.

[58] This layout is known as "Bent Axis",[59] After the burial, the upper corridors were meant to be filled with rubble and the entrance to the tomb hidden.

The early tombs were decorated with scenes from Amduat ('That Which is in the Underworld'), which describes the journey of the sun god through the twelve hours of the night.

The opulence of his grave goods notwithstanding, Tutankhamun was a relatively minor king, and other burials probably had more numerous treasures.

It was not an official designation, and the actual existence of a tomb at all was dismissed by the Supreme Council of Antiquities,[80] prior to finally excavating and describing it during 2011–2012.

[86] Ramesses II's son and eventual successor, Merenptah's tomb has been open since antiquity; it extends 160 metres, ending in a burial chamber that once contained a set of four nested sarcophagi.

The tomb extends a total distance of 105 metres into the hillside, including extensive side chambers that were neither decorated nor finished.

Some attempt at using the open tombs was made at the start of the Twenty-first Dynasty, with the High Priest of Amun, Pinedjem I, adding his cartouche to KV4.

Located in the cliffs overlooking the Mortuary Temple of Hatshepsut, this mass reburial contained a large number of royal mummies.

Thieves often looted the chambers and bodies of mummies and took with them precious metals and stones, the most common gold and silver, linens and ointments or unguents.