Van Orden v. Perry

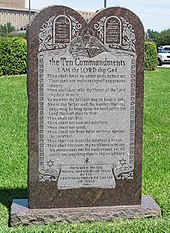

In a suit brought by Thomas Van Orden of Austin, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled in November 2003 that the displays were constitutional, on the grounds that the monument conveyed both a religious and secular message.

The Court chose not to employ the oft-used Lemon test in its analysis, reasoning that the display at issue was a "passive monument.

It was donated to the State of Texas by the Fraternal Order of Eagles, a civic organization, who paid in full for the cost of the statute.

The surrounding 22 acres (89,000 m2) contained 17 monuments and 21 historical markers commemorating the "people, ideals, and events that compose Texan identity."

A native Texan, Van Orden passed by the monument frequently when he would go to the Texas Supreme Court building to use its law library.

The District Court held that the State had a "valid secular purpose" in accepting the statute from the Fraternal Order of Eagles in recognition of their civic "efforts to reduce juvenile delinquency", and that a reasonable person would not interpret the monument as an endorsement of religion.

Although the Lemon Test has not been overruled, sometimes to the open dismay of conservative Justices (Justice Antonin Scalia once remarked that it "repeatedly sits up in its grave and shuffles abroad, after being repeatedly killed and buried"), the plurality did not think it was "useful in dealing with the sort of passive monument that Texas has erected on its Capitol grounds".

Instead, they created a historic intent test: "There is an unbroken history of official acknowledgement by all three branches of government of the role of religion in American life from at least 1789".

And that inquiry requires us to consider the context of the display.He concurs in the judgment based on his analysis of other facts, including the length of time the display of the monument went unchallenged.

At the same time to reach a contrary conclusion here, based primarily on the religious nature of the tablets' text would, I fear, lead the law to exhibit a hostility toward religion that has no place in our Establishment Clause traditions.

Zelman, 536 U.S. at 717-729 (Breyer, J., dissenting)Scalia's concurrence calls for "adopting an Establishment Clause jurisprudence that is in accord with our Nation's past and present practices, and that can be consistently applied".