Vaudeville

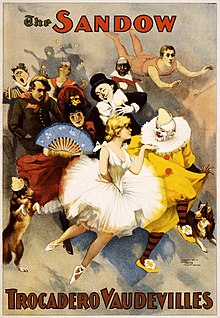

Vaudeville (/ˈvɔːd(ə)vɪl, ˈvoʊ-/;[1] French: [vodvil] ⓘ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment which began in France at the end of the 19th century.

[2] A Vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition or light poetry, interspersed with songs and dances.

[4] In some ways analogous to music hall from Victorian Britain,[5] a typical North American vaudeville performance was made up of a series of separate, unrelated acts grouped together on a common bill.

Vaudeville developed from many sources, including the concert saloon, minstrelsy, freak shows, dime museums, and literary American burlesque.

[7] In his Connections television series, science historian James Burke argues that the term is a corruption of the French Vau de Vire 'Vire River Valley', an area known for its bawdy drinking songs and where Basselin lived.

In the US, as early as the first decades of the 19th century, theatergoers could enjoy a performance consisting of Shakespeare plays, acrobatics, singing, dancing, and comedy.

[16] Pastor opened his first "Opera House" on the Bowery in 1865, later moving his variety theater operation to Broadway and, finally, to Fourteenth Street near Union Square.

[17] Hoping to draw a potential audience from female and family-based shopping traffic uptown, Pastor barred the sale of liquor in his theatres, eliminated bawdy material from his shows, and offered gifts of coal and hams to attendees.

They enabled a chain of allied vaudeville houses that remedied the chaos of the single-theatre booking system by contracting acts for regional and national tours.

Acts that violated this ethos (e.g., those that used words such as "hell") were admonished and threatened with expulsion from the week's remaining performances or were canceled altogether.

Featuring a bill stocked with inventive novelty acts, national celebrities, and acknowledged masters of vaudeville performance (such as comedian and trick roper Will Rogers), the Palace provided what many vaudevillians considered the apotheosis of remarkable careers.

Black patrons, often segregated into the rear of the second gallery in white-oriented theatres, had their own smaller circuits, as did speakers of Italian and Yiddish (see below).

Consequently, Erdman adds that female Vaudeville performers such as Julie Mackey and Gibson's Bathing Girls began to focus less on talent and more on physical appeal through their figure, tight gowns, and other revealing attire.

She worked largely in comedy and gained acclaim and success due to her willingness to step into other's roles who had fallen ill, and were otherwise unable to perform.

Many years later, their act had taken off and with performances in both vaudeville and burlesque at famous music halls, until Irwin decided to continue her career on her own.

This is when she began experimenting with improvisational comedy and quickly found her unique success, even taking her performances global with acts in the U.K. Sophie Tucker, a Russian Jewish immigrant, was told by promoter Chris Brown that she was not attractive enough to succeed in show business without doing Blackface, so she performed that way for the first two years onstage, until one day she decided to go without it, and achieved much greater success being herself from that point on, especially with her song "Some of These Days".

[32] Other 20th century women performers who started in Vaudeville included blues singers Ma Rainey, Ida Cox and Bessie Smith.

[38] In addition to vaudeville's prominence as a form of American entertainment, it reflected the newly evolving urban inner-city culture and interaction of its operators and audience.

The often hostile immigrant experience in their new country was now used for comic relief on the vaudeville stage, where stereotypes of different ethnic groups were perpetuated.

In addition to interpreting visual ethnic caricatures, the Irish American ideal of transitioning from the shanty[47] to the lace curtain[43] became a model of economic upward mobility for immigrant groups.

Lured by greater salaries and less arduous working conditions, many performers and personalities, such as Al Jolson, W. C. Fields, Mae West, Buster Keaton, the Marx Brothers, Jimmy Durante, Bill "Bojangles" Robinson, Edgar Bergen, Fanny Brice, Burns and Allen, and Eddie Cantor, used the prominence gained in live variety performance to vault into the new medium of cinema.

The line between live and filmed performances was blurred by the number of vaudeville entrepreneurs who made more or less successful forays into the movie business.

Earlier in the century, many vaudevillians, cognizant of the threat represented by cinema, held out hope that the silent nature of the "flickering shadow sweethearts" would prevent movies from ever overtaking vaudeville in popularity.

However, with the introduction of talking pictures in 1926, the burgeoning film studios removed what had remained the chief difference in favor of live theatrical performance: spoken dialogue.

The newly-formed RKO studios took over the famed Orpheum vaudeville circuit and swiftly turned it into a chain of full-time movie theatres.

Vaudeville also suffered due to the rise of broadcast radio following the greater availability of inexpensive receiver sets later in the decade.

[49] Though talk of its resurrection was heard during the 1930s and later, the demise of the supporting apparatus of the circuits and the higher cost of live performance made any large-scale renewal of vaudeville unrealistic.

The most striking examples of Gilded Age theatre architecture were commissioned by the big time vaudeville magnates and stood as monuments of their wealth and ambition.

These stages could offer anything from child performers to contra-dances to visits by Santa to local, musical talent, to homemade foods such as whoopee pies.

Vaudevillian techniques can commonly be witnessed on television and in movies, remarkably in the recent, worldwide phenomenon of TV shows such as America's Got Talent.