Buddhist vegetarianism

The Mahayana schools generally recommend a vegetarian diet, claiming that Gautama Buddha set forth in some of the sutras that his followers must not eat the flesh of any sentient being.

Many Buddhist vegetarians also oppose meat-eating based on scriptural injunctions against flesh-eating recorded in Mahayana sutras.

Vegetarianism in ancient IndiaThroughout the whole country the people do not kill any living creature, nor drink intoxicating liquor, nor eat onions or garlic.

In that country they do not keep pigs and fowls, and do not sell live cattle; in the markets there are no butchers’ shops and no dealers in intoxicating drink.

The Buddha in the Aṅguttara Nikāya 3.38 Sukhamala Sutta, before his enlightenment, describes his family being wealthy enough to provide non-vegetarian meals even to his servants.

After becoming enlightened, he respectfully accepted any kind of alms food offered with good intention, including meat (within the limitations described above), fruits and vegetables.

[10]But this is not, strictly speaking, a dietary rule because the Buddha, on one particular occasion, specifically refused suggestions by Devadatta to institute vegetarianism in the Sangha.

[12] There were monastic guidelines prohibiting consumption of 10 types of meat: that of humans, elephants, horses, dogs, snakes, lions, tigers, leopards, bears and hyenas.

"[15]The Buddha in certain Mahayana sutras very vigorously and unreservedly denounced the eating of meat, mainly on the grounds that such an act is linked to the spreading of fear amongst sentient beings (who can allegedly sense the odor of death that lingers about the meat-eater and who consequently fear for their own lives) and violates the bodhisattva's fundamental cultivation of compassion.

Moreover, according to the Buddha in the Aṅgulimālīya Sūtra, since all beings share the same "Dhatu" (spiritual Principle or Essence) and are intimately related to one another, killing and eating other sentient creatures is tantamount to a form of self-killing and cannibalism.

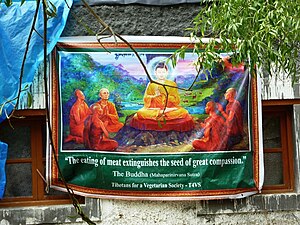

In the Mahāyāna Mahāparinirvāṇa Sūtra, which presents itself as the final elucidatory and definitive Mahayana teachings of the Buddha on the very eve of his death, the Buddha states that "the eating of meat extinguishes the seed of Great Kindness", adding that all and every kind of meat and fish consumption (even of animals found already dead) is prohibited by him.

Henceforth, when monastics from the Indian geographical sphere of influence migrated to China from the year 65 CE on, they met followers who provided them with money instead of food.

From those days onwards, Chinese monastics, and others who came to inhabit northern countries, cultivated their own vegetable plots and bought food in the market.

He ‘changed the perception’ of others, when he once caused his followers to save a female yak from being butchered, and he continually urged his disciples to forswear the killing of animals.

Rinpoche, master of Drikungpa, said like this, "My students, whomever are eating or using meat and calling it tsokhor or tsok, then these people are completely deserting me and going against the dharma."

In China, Korea,[35] Vietnam, Taiwan and their respective diaspora communities, monks and nuns are expected to abstain from meat and, traditionally, eggs and dairy, in addition to the fetid vegetables; also known as the five pungent spices (Chinese: 五辛; pinyin: Wǔ xīn) – traditionally garlic, Allium chinense, asafoetida, shallot, and Allium victorialis (victory onion or mountain leek), although in modern times this rule is often interpreted to include other vegetables of the onion genus, as well as coriander – this is called pure vegetarianism or veganism (Chinese: 純素/淨素齋; pinyin: Chún sù/Jìng sù/Zhāi) and or five pungent spices vegetarianism (Chinese: 五辛素; pinyin: Wǔ xīn sù).

Pure Vegetarianism or Veganism is Indic in origin and is still practiced in India by some adherents of Dharmic religions such as Jainism and in the case of Hinduism, lacto-vegetarianism with the additional abstention of pungent or fetid vegetables.

In 675, Emperor Tenmu issued an edict prohibiting eating the meat of cows, horses, dogs, monkeys, and roosters, as recorded in the Nihon Shoki.

[38] Tenmu was a strong proponent of Buddhism, and these views were bolstered by Shinto perspectives that reviewed blood and dead bodies as impure (Japanese: 穢れ kegare) and to be avoided.

References to hunting and eating deer and wild boar continued throughout the ancient and medieval period into the 16th century as an occasional part of the diet for all but those in the poorer agrarian classes.

The court nobles also ate red meat occasionally, despite being obliged to follow Buddhist principles closely, although it was viewed as inferior to eating fish and birds.

(円戒 yuán jiè) During the 12th century, a number of monks from Tendai sects founded new schools (Zen, Pure Land Buddhism) and de-emphasised vegetarianism.

Buddhist vegetarianism (aka Shojin Ryori), also dictates Kinkunshoku (禁葷食) which is to not use meat as well as Gokun (五葷 5 vegetables from the allium family) in their cooking.

[40] The removal of the ban encountered resistance and in one notable response, ten monks attempted to break into the Imperial Palace.

However, records show that in Tibet, the practice of vegetarianism was encouraged as early as the 14th and 15th centuries by renowned Buddhist teachers such as Chödrak Gyatso and Mikyö Dorje, 8th Karmapa Lama.

[44] Contemporary Buddhist teachers such as the Dalai Lama, and The 17th Karmapa Ogyen Trinley Dorje, invite their audiences to adopt vegetarianism whenever they can.