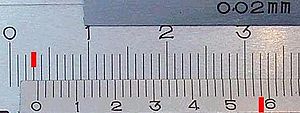

Vernier scale

A vernier may be used on circular or straight scales where a simple linear mechanism is adequate.

Examples are calipers and micrometers to measure to fine tolerances, on sextants for navigation, on theodolites in surveying, and generally on scientific instruments.

The first caliper with a secondary scale, which contributed extra precision, was invented in 1631 by French mathematician Pierre Vernier (1580–1637).

[1] Its use was described in detail in English in Navigatio Britannica (1750) by mathematician and historian John Barrow.

[2] While calipers are the most typical use of vernier scales today, they were originally developed for angle-measuring instruments such as astronomical quadrants.

The name "vernier" was popularised by the French astronomer Jérôme Lalande (1732–1807) through his Traité d'astronomie (2 vols) (1764).

Let the measure of the smallest main-scale reading, that is the distance between two consecutive graduations (also called its pitch) be S, and the distance between two consecutive vernier scale graduations be V, such that the length of (n − 1) main-scale divisions is equal to n vernier-scale divisions.

Then Vernier scales work so well because most people are especially good at detecting which of the lines is aligned and misaligned, and that ability gets better with practice, in fact far exceeding the optical capability of the eye.

[5] Historically, none of the alternative technologies exploited this or any other hyperacuity, giving the vernier scale an advantage over its competitors.

This section includes references to techniques which use the Vernier principle to make fine-resolution measurements.

The method uses a frequency-comb laser combined with a high-finesse optical cavity to produce an absorption spectrum in a highly parallel manner.