Villard Houses

Designed by the architect Joseph Morrill Wells of McKim, Mead & White in the Renaissance Revival style, the residences were erected in 1884 for Henry Villard, the president of the Northern Pacific Railway.

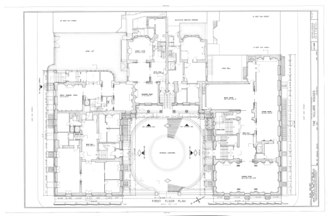

The building comprises six residences in a U-shaped plan, with wings to the north, east, and south surrounding a courtyard on Madison Avenue.

Among the artists who worked on the interiors were art-glass manufacturer John La Farge, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, and painter Maitland Armstrong.

[5] The rest of the residences occupy part of a second land lot, which is shared with the Lotte New York Palace Hotel immediately to the east.

[25] The lady chapel in the cathedral had not yet been built, so St. Patrick's eastern end was a flat wall flanked by a rectory and an archbishop's house.

[18] The courtyard was designed as both a symbol of Villard's wealth and, according to architectural writer Richard Guy Wilson, an "urban gesture" to traffic on Madison Avenue.

[15] When the Helmsley Palace Hotel was built in the late 1970s and the south wing was converted to a bar, the former south-wing entrance was turned into an exit-only doorway.

The south-wing doorway was close to the Lady chapel behind St. Patrick's Cathedral,[45] and a state law mandated that bar entrances be at least 200 feet (61 m) from any house of worship.

[53] These may have included artistic-glass manufacturer John La Farge, sculptor Augustus Saint-Gaudens, painter Francis Lathrop, and mosaic artist David Maitland Armstrong.

[54] Candace Wheeler may have made the embroideries;[54][57] Pasquali and Aeschlimann may have installed the mosaics;[56] and Ellin & Kitson likely performed some of the stone carving.

[18][59][75] The family of the journalist Whitelaw Reid used these drawing rooms as a ballroom during the early 20th century,[76][77] with green marble columns and a gilded ceiling.

[70][67] Saint-Gaudens installed five plaster casts on each of the north and south walls, which were copies of "singing angels" that Luca della Robbia designed for the Florence Cathedral.

[74][78][80] John La Farge designed two lunettes or curved panels called "Art" and "Music", as well as leaded glass windows on the east wall.

[27][59] The second-story hallway had a gilded ceiling, embossed-leather walls, and a large mantelpiece;[27] the decorators used leather and wood to give the space a more intimate feeling.

[17][105] The Park Avenue railroad line ran directly east of the site, and there was also an orphanage to the north, St. Patrick's Cathedral to the west, and the Columbia College campus to the south.

[105] Villard paid $260,000 (equivalent to about $7.21 million in 2023) for the land after St. Patrick's trustees declined a higher offer from another potential buyer who wanted to build an entertainment venue there.

[17][22][50] The Real Estate Record and Guide speculated that the mansions were arranged to "secure privacy and get rid of tramps, and to live in a quiet and secluded way", similar to dwellings in the suburbs of London and Paris.

The writer Elizabeth Hawes wrote that, by doing so, Villard wanted to create "a pleasant neighborhood unit" that positively impacted future urban developments.

[21] A later New York Times article said that Villard had planned the entire complex as his own residence, but he was obligated to split it into multiple smaller units when his wealth declined.

[76] Details of the design were revised through late 1881, when McKim temporarily left New York City to work on a railroad terminal for Villard in Portland, Oregon.

[73][106] White reassigned his projects to various junior architects in his office, and Joseph M. Wells agreed to take over the design of the Villard Houses from the firm's remaining partner, William Rutherford Mead.

In May 1882, McKim, Mead & White submitted plans to the Bureau of Buildings for a four-story residence at 451 Madison Avenue (on the corner with 50th Street), measuring 100 by 60 feet (30 by 18 m).

[114] One residence on the north wing, the unit with a doorway facing the courtyard, was to have been occupied by Villard's adviser, Horace White, but this did not happen.

[118] The residence at 24 East 51st Street was purchased by Scribner's Monthly publisher Roswell Smith in September 1886,[134] and Babb, Cook & Willard designed an expansion of Number 24 soon after.

[167] At the opening of the Military Services Club, New York City mayor Fiorello La Guardia declared, "You won't see any more private mansions like this.

[173] Number 457, as well as a one-third interest in the courtyard, was acquired the same year by the publishing company Random House, which renovated the residence into its own offices.

[171][196][197] According to its real estate adviser, John J. Reynolds, the archdiocese wanted to preserve the houses so there would be open space in front of St. Patrick's Cathedral.

[200] The 1973–1974 stock market crash had led to a decline in demand for real estate, so the Villard Houses was vacant except for Capital Cities' offices.

At the time, James W. Rhodes estimated that 99 percent of the facade's original brownstone remained; some of the pieces for the restoration had come from the demolished rear portions of the houses.

[260] The Christian Science Monitor wrote in 1934 that the buildings retained "the same dignity that accompanied them in 1883" and that their construction had spurred the start of interior decoration.