Violence

[11]Maltreatment (including violent punishment) involves physical, sexual and psychological/emotional violence; and neglect of infants, children and adolescents by parents, caregivers and other authority figures, most often in the home but also in settings such as schools and orphanages.

[1][15] Consequences of child maltreatment include impaired lifelong physical and mental health, and social and occupational functioning (e.g. school, job, and relationship difficulties).

Youth violence greatly increases the costs of health, welfare and criminal justice services; reduces productivity; decreases the value of property; and generally undermines the fabric of society.

Since the victims of youth-on-youth violence may not be able to attend school or work because of their physical and/or mental injuries, it is often up to their family members to take care of them, including paying their daily living expenses and medical bills.

[25] It is important for youth exposed to violence to understand how their bodies may react so they can take positive steps to counteract any possible short- and long-term negative effects (e.g., poor concentration, feelings of depression, heightened levels of anxiety).

[11]Emotional or psychological violence includes restricting a child’s movements, denigration, ridicule, threats and intimidation, discrimination, rejection and other non-physical forms of hostile treatment.

[38] Elder maltreatment is a single or repeated act, or lack of appropriate action, occurring within any relationship where there is an expectation of trust which causes harm or distress to an older person.

Many strategies have been implemented to prevent elder maltreatment and to take action against it and mitigate its consequences including public and professional awareness campaigns, screening (of potential victims and abusers), caregiver support interventions (e.g. stress management, respite care), adult protective services and self-help groups.

[c][citation needed] Brad Evans states that violence "represents a violation in the very conditions constituting what it means to be human as such", "is always an attack upon a person's dignity, their sense of selfhood, and their future", and "is both an ontological crime ... and a form of political ruination".

[62] On the other hand, individual protective factors include an intolerance towards deviance, higher IQ and GPA, elevated popularity and social skills, as well as religious beliefs.

Despite public or media opinion, national studies have indicated that severe mental illness does not independently predict future violent behavior, on average, and is not a leading cause of violence in society.

The effectiveness of interventions addressing dating violence and sexual abuse among teenagers and young adults by challenging social and cultural norms related to gender is supported by some evidence.

[124] In the 20th century in acts of democide governments may have killed more than 260 million of their own people through police brutality, execution, massacre, slave labour camps, and sometimes through intentional famine.

[1] Rather than focusing on individuals, the public health approach aims to provide the maximum benefit for the largest number of people, and to extend better care and safety to entire populations.

He defined violence as an issue that public health experts needed to address and stated that it should not be the primary domain of lawyers, military personnel, or politicians.

Second, the magnitude of the problem and its potentially severe lifelong consequences and high costs to individuals and wider society call for population-level interventions typical of the public health approach.

The state, in the grip of a perceived, potential crisis (whether legitimate or not) takes preventative legal measures, such as a suspension of rights (it is in this climate, as Agamben demonstrates, that the formation of the Social Democratic and Nazi government's lager or concentration camp can occur).

[141] At the scale of the body, in the state of exception, a person is so removed from their rights by "juridical procedures and deployments of power"[141] that "no act committed against them could appear any longer as a crime";[141] in other words, people become only homo sacer.

As part of Pol Pot's "ideological intent…to create a purely agrarian society or cooperative",[142] he "dismantled the country's existing economic infrastructure and depopulated every urban area".

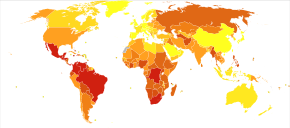

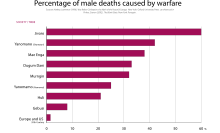

[155][156] Although there is a widespread perception that war is the most dangerous form of armed violence in the world, the average person living in a conflict-affected country had a risk of dying violently in the conflict of about 2.0 per 100,000 population between 2004 and 2007.

[161] Other evidence suggests that organized, large-scale, militaristic, or regular human-on-human violence was absent for the vast majority of the human timeline,[162][163][164] and is first documented to have started only relatively recently in the Holocene, an epoch that began about 11,700 years ago, probably with the advent of higher population densities due to sedentism.

[163] Social anthropologist Douglas P. Fry writes that scholars are divided on the origins of possible increase of violence—in other words, war-like behavior: There are basically two schools of thought on this issue.

Here, warfare is a latecomer on the cultural horizon, only arising in very specific material circumstances and being quite rare in human history until the development of agriculture in the past 10,000 years.

For instance, the rise of agriculture provided a significant increase in the number of individuals that a region could sustain over hunter-gatherer societies, allowing for development of specialized classes such as soldiers, or weapons manufacturers.

[169] Fry explores Keeley's argument in depth and counters that such sources erroneously focus on the ethnography of hunters and gatherers in the present, whose culture and values have been infiltrated externally by modern civilization, rather than the actual archaeological record spanning some two million years of human existence.

Victims may engage in high-risk behaviours such as alcohol and substance misuse and smoking, which in turn can contribute to cardiovascular disorders, cancers, depression, diabetes and HIV/AIDS, resulting in premature death.

In countries with high levels of violence, economic growth can be slowed down, personal and collective security eroded, and social development impeded.

For societies, meeting the direct costs of health, criminal justice, and social welfare responses to violence diverts many billions of dollars from more constructive societal spending.

In view of these considerations, violence may be defined as follows: any action, verbal or nonverbal, oral or written, physical or psychical, active or passive, public or private, individual or institutional/societal, human or divine, in whatever degree of intensity, that abuses, violates, injures, or kills.

Some of the most pervasive and most dangerous forms of violence are those that are often hidden from view (against women and children, especially); just beneath the surface in many of our homes, churches, and communities is abuse enough to freeze the blood.