Virginia Hall

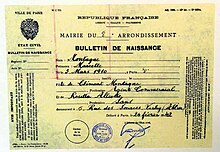

Virginia Hall Goillot DSC, Croix de Guerre, MBE (April 6, 1906 – July 8, 1982), code named Marie and Diane, was an American who worked with the United Kingdom's clandestine Special Operations Executive (SOE) and the American Office of Strategic Services (OSS) in France during World War II.

The objective of SOE and OSS was to conduct espionage, sabotage and reconnaissance in occupied Europe against the Axis powers, especially Nazi Germany.

[4] She was a thirty-five-year-old journalist from Baltimore, conspicuous by reddish hair, a strong American accent, an artificial foot, and an imperturbable temper; she took risks often but intelligently.

After being diagnosed with gangrene, on the brink of death, as a last-ditch attempt her leg was amputated below the knee and replaced with a wooden appendage which she named "Cuthbert".

After the defeat of France in June 1940, she made her way to Spain where, by chance, she met a British intelligence officer named George Bellows.

[7][11] Hall joined the SOE in April 1941 and after training arrived in Vichy France, unoccupied by Germany and nominally independent at that time, on August 23, 1941.

)[a] Hall's cover was as a reporter for the New York Post which gave her license to interview people, gather information and file stories filled with details useful to military planners.

Guérin made several safehouses available to Hall and passed along tidbits of information she and her female employees heard from German officers visiting the brothel.

In the absence of an SOE wireless operator, her access to the American diplomatic pouch was the only means the few agents left at large in France had of communicating with London.

She continued building contacts in southern France and she assisted in the brief missions of SOE agents Peter Churchill and Benjamin Cowburn and earned high compliments from both.

When a suspicious Heslop demanded to know who "Cuthbert" was she showed him by banging her wooden foot against a table leg producing a hollow sound.

The Gestapo flooded Vichy, France with 500 agents, and the Abwehr also stepped up operations to infiltrate and destroy the fledgling French Resistance and the SOE networks.

[24] In May 1942, Hall had agreed to have messages from the Gloria Network, a French-run resistance movement based in Paris, transmitted to SOE in London.

Alesch also made contact with Hall in August, claiming to be an agent of Gloria and offering intelligence of apparently high value.

Alesch was able to penetrate Hall's network of contacts, including the capture of wireless operators and the sending of false messages to London in her name.

Hall anticipated correctly that the suppression by the Gestapo and Abwehr would become even more severe and she fled Lyon without telling anyone, including her closest contacts.

She escaped by train from Lyon to Perpignan, then, with a guide, walked over a 7,500 foot pass in the Pyrenees to Spain, covering up to 50 miles over two days in considerable discomfort.

After arriving in Spain, she was arrested by the Spanish authorities for illegally crossing the border, but the American Embassy eventually secured her release.

She worked for SOE for a time in Madrid, then returned to London in July 1943 where she was quietly made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE).

She was hired by the Special Operations Branch at the low rank and pay of a second lieutenant, and she returned to France on March 21, 1944, arriving by motor gunboat at Beg-an-Fry east of Roscoff in Brittany.

The OSS teams' objective was to arm and train the resistance groups, called Maquis, so they could conduct sabotage and guerrilla activities to support the Allied invasion of Normandy, which would take place on June 6, 1944.

[33] From March to July 1944, Hall roamed around France south of Paris, posing sometimes as an elderly milkmaid (and on one occasion selling cheese she had made to a group of German soldiers).

She found and organized drop zones, established several safe houses, and made and renewed contacts in the Resistance, notably with Philippe de Vomecourt.

[34][35] Hall was next given the job of helping the Maquis in southern France harass the Germans in support of the Allied invasion of the south, Operation Dragoon, which would take place on August 15, 1944.

"[39] Hall and several of the British and American military officers working for her left the Haute Loire and arrived in Paris on September 22.

Her closest associates, brothel-owner Germaine Guérin and gynecologist Jean Rousset, had both been captured by the Germans and sent to concentration camps, but they survived.

In the 1950s, she again headed ultra secret paramilitary operations in France as a model for setting up resistance groups in several European countries in case of a Soviet attack.

General William Joseph Donovan personally awarded Virginia Hall a Distinguished Service Cross in September 1945 in recognition of her efforts in France.

She was made an honorary Member of the Order of the British Empire (MBE), and was awarded the Croix de Guerre with Palme by France.

[47] Hall's refusal to talk and write about her World War II experiences resulted in her slipping into obscurity during her lifetime, but her death "triggered a new curiosity" which persisted into the 21st century.