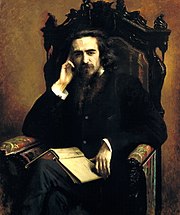

Vladimir Solovyov (philosopher)

[5] Vladimir Solovyov's mother Polyxena Vladimirovna (née Romanova, d. 1909) belonged to a family of Polish origin and among her ancestors was the philosopher Gregory Skovoroda (1722–1794).

[7][page needed] Positivism, according to Solovyov, validates only the phenomenon of an object, denying the intuitive reality that people experience as part of their consciousness.

It is clear from Solovyov's work that he accepted papal primacy over the Universal Church,[9][10][11] but there is not enough evidence, as of 2022[update], to support the claim that he ever officially embraced Roman Catholicism.

As an active member of Society for the Promotion of Culture Among the Jews of Russia, he spoke Hebrew and struggled to reconcile Judaism and Christianity.

[13] Solovyov's attempts to chart a course of civilization's progress toward an East-West Christian ecumenism developed an increasing bias against Asian cultures—which he had initially studied with great interest.

[14] Solovyov spent his final years obsessed with fear of the "Yellow Peril", warning that soon the Asian peoples, especially the Chinese, would invade and destroy Russia.

[15] Solovyov further elaborated this theme in his apocalyptic short-story "Tale of the Antichrist" (published in the Nedelya newspaper on 27 February 1900), in which China and Japan join forces to conquer Russia.

[16] Solovyov never married or had children, but he pursued idealized relationships as immortalized in his spiritual love-poetry, including with two women named Sophia.

[24] His teachings on Sophia, conceived as the merciful unifying feminine wisdom of God comparable to the Hebrew Shekinah or various goddess traditions,[25] have been deemed a heresy by Russian Orthodox Church Outside Russia and as unsound and unorthodox by the Patriarchate of Moscow.

[26] This condemnation, however, was not agreed upon by other jurisdictions of the Orthodox church and was directed specifically against Sergius Bulgakov who continued to be defended by his own hierarch Metropolitan Evlogy until his death.

She was not a fourth hypostasis in the Godhead, nor a fallen fragment of God, nor a literal world-soul, nor an eternal hypostasis who became incarnate as the Mother of God, nor most certainly the ‘feminine aspect of deity.’ Solovyov possessed too refined a mind to fall prey to the lure of cultic mythologies or childish anthropomorphisms, despite his interest in Gnosticism (or at least in its special pathos); and all such characterizations of the figure of Sophia are the result of misreadings (though, one must grant, misreadings partly occasioned by the young Solovyov’s penchant for poetic hyperbole).