Volcanism on Io

An anomalously high thermal flux, compared to the other Galilean satellites, was discovered during measurements taken at an infrared wavelength of 10 μm while Io was in Jupiter's shadow.

[12] These results were considerably different from measurements taken at wavelengths of 20 μm, which suggested that Io had similar surface properties to the other Galilean satellites.

The group considered volcanic activity at the time, in which case the data was fit into a region on Io 8,000 square kilometres (3,100 sq mi) in size at 600 K (300 °C; 600 °F).

[15] Shortly before the Voyager 1 encounter, Stan Peale, Patrick Cassen, and R. T. Reynolds published a paper in the journal Science predicting a volcanically modified surface and a differentiated interior, with distinct rock types rather than a homogeneous blend.

Instead, Voyager 1 observed a multi-coloured surface, pockmarked with irregular-shaped depressions, which lacked the raised rims characteristic of impact craters.

Voyager 1 also observed flow features formed by low-viscosity fluid and tall, isolated mountains that did not resemble terrestrial volcanoes.

By processing images of Io to enhance the visibility of background stars, navigation engineer Linda Morabito found a 300-kilometre (190 mi) tall cloud along its limb.

[19] Io's main source of internal heat comes from the tidal forces generated by Jupiter's gravitational pull.

[4][20] In the Earth, these internal heat sources drive mantle convection, which in turn causes volcanism through plate tectonics.

[21] The tidal heating of Io is dependent on its distance from Jupiter, its orbital eccentricity, the composition of its interior, and its physical state.

[23] Analysis of Voyager images led scientists to believe that the lava flows on Io were composed mostly of various forms of molten elemental sulfur.

In addition, temperature measurements of thermal emission at Loki Patera taken by Voyager 1's Infrared Interferometer Spectrometer and Radiometer (IRIS) instrument were consistent with sulfur volcanism.

[25] The contradiction between the structural evidence and the spectral and temperature data following the Voyager flybys led to a debate in the planetary science community regarding the composition of Io's lava flows, whether they were composed of silicate or sulfurous materials.

[15][28] In addition, modeling of silicate lava flows on Io suggested that they cooled rapidly, causing their thermal emission to be dominated by lower temperature components, such as solidified flows, as opposed to the small areas covered by still molten lava near the actual eruption temperature.

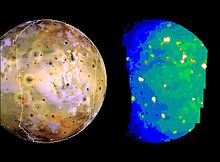

[29] Silicate volcanism, involving basaltic lava with mafic to ultramafic (magnesium-rich) compositions, was confirmed by the Galileo spacecraft in the 1990s and 2000s from temperature measurements of Io's numerous hot spots, locations where thermal emission is detected, and from spectral measurements of Io's dark material.

Temperature measurements from Galileo's Solid-State Imager (SSI) and Near-Infrared Mapping Spectrometer (NIMS) revealed numerous hot spots with high-temperature components ranging from at least 1,200 K (900 °C; 1,700 °F) to a maximum of 1,600 K (1,300 °C; 2,400 °F), like at the Pillan Patera eruption in 1997.

[5] Spectral observations of Io's dark material suggested the presence of orthopyroxenes, such as enstatite, which are magnesium-rich silicate minerals common in mafic and ultramafic basalt.

They differ in terms of duration, energy released, brightness temperature (determined from infrared imaging), type of lava flow, and whether it is confined within volcanic pits.

[6] Intra-patera eruptions occur within volcanic depressions known as paterae,[35] which generally have flat floors bounded by steep walls.

Unlike similar features on Earth and Mars, these depressions generally do not lie at the peak of shield volcanoes and are larger, with an average diameter of 41 kilometres (25 mi).

Whatever the formation mechanism, the morphology and distribution of many paterae suggest that they are structurally controlled, with at least half bounded by faults or mountains.

Over time, because the solidified lava is denser than the still-molten magma below, this crust can founder, triggering an increase in thermal emission at the volcano.

A relatively inactive flow field named Lei-Kung Fluctus covers more than 125,000 square kilometres (48,000 sq mi), an area slightly larger than Nicaragua.

For example, the leading edge of the Prometheus flow field moved 75 to 95 kilometres (47 to 59 mi) between observations by Voyager in 1979 and Galileo in 1996.

[51] Explosion-dominated eruptions occur when a body of magma (called a dike) from deep within Io's partially molten mantle reaches the surface at a fissure.

[55] Observations by Galileo suggest lava coverage rates at Pillan between 1,000 and 3,000 square metres (11,000 and 32,000 sq ft) per second during the 1997 eruption.

[53] The 1997 Pillan eruption produced a 400 km (250 mi) wide deposit of dark, silicate material and bright sulfur dioxide.

[8] The discovery of volcanic plumes at Pele and Loki in 1979 provided conclusive evidence that Io was geologically active.

[60] Prometheus-type plumes are dust-rich, with a dense inner core and upper canopy shock zone, giving them an umbrella-like appearance.

These plumes often form bright circular deposits, with a radius ranging between 100 and 250 kilometres (62 and 155 mi) and consisting primarily of sulfur dioxide frost.