Volkstaat

The end of apartheid and the establishment of universal suffrage in South Africa in 1994 left some Afrikaners feeling disillusioned and marginalised by the political changes, which resulted in a proposal for an independent Volkstaat.

Supporters of the proposal have established several land cooperatives in Orania in the Northern Cape province and Kleinfontein in Gauteng as practical implementations of the idea.

The underlying principle of apartheid was racial separatism, and the means by which this was implemented, such as the homeland system of bantustans, were biased against the non-European majority as they excluded them from exercising their rights in the broader South Africa.

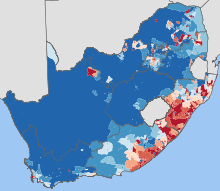

Avstig proposed a Volkstaat in the Northern Cape province, in a largely rural and minimally developed region.

[9][10] A 1999 pre-election survey suggested that the 26.9% of Afrikaners wanting to emigrate, but unable to, represented a desire for a solution such as a Volkstaat.

[12] The newspaper's analysis of this was that the idea of a Volkstaat was doodgebore (stillborn) and that its advocates had been doing nothing but tread water for the past two decades, although it did suggest that the poll was a measure of dissatisfaction among Afrikaners.

[13] Dissatisfaction with life in post-apartheid South Africa is often cited as an indication of support for the idea of a Volkstaat among Afrikaners.

[14][15] A poll carried out by the Volkstaat Council among white people in Pretoria identified crime, economic problems, personal security, affirmative action, educational standards, population growth, health services, language and cultural rights, and housing as reasons to support the creation of Volkstaat.

The Freedom Front advocates following the Belgium, Canada and Spain models of granting territorial autonomy to linguistic minorities, believing it the only way to protect the rights of Afrikaner people.

Plans include a demand for land, such as Stellaland and Goshen, that they claim is legally theirs in terms of the Sand River Convention of 1852 and other historical treaties, through the International Court of Justice in The Hague if necessary.

Die Boeremag (The Farmer-Might) advocated for a violent overthrow of the African National Congress government and sought to restore apartheid-era policies and create a separate homeland for Afrikaners.

[19] Penuell Maduna, one of the leading ANC negotiators during the transition era, noted that Afrikaner organizations could not agree on the borders of the new Volkstaat.

He noted a proposal to create a Volkstaat that would stretch from majority-white neighborhoods in Pretoria to the Atlantic Ocean, which was seen as unacceptable by the ANC.

[20] On 5 June 1998, Mohammed Valli Moosa (then minister of constitutional development in the African National Congress (ANC) government) stated during a parliamentary budget debate that "the ideal of some Afrikaners to develop the North Western Cape as a home for the Afrikaner culture and language within the framework of the Constitution and the charter of human rights is viewed by the government as a legitimate ideal.

[25] Orania is currently petitioning the government to become a separate municipality and in the meantime their (transitional) representative council will remain in place indefinitely with all its powers, rights and duties.

The requirements set by international law are explained by Prof C. Lloyd Brown-John of the University of Windsor (Canada), as follows: "A minority who are geographically separate and who are distinct ethnically and culturally and who have been placed in a position of subordination may have a right to secede.

[33] The rights awarded to minorities were formally asserted by the United Nations General Assembly when it adopted resolution 47/135 on 18 December 1992.