Volta Laboratory and Bureau

[6] The current building, a U.S. National Historic Landmark, was constructed in 1893 under the direction of Alexander Graham Bell to serve as a center of information for deaf and hard of hearing persons.

The following year, the French government awarded Bell the Volta Prize of 50,000 francs (approximately US$330,000 in current dollars[7]) for the invention of the telephone.

[3] The Volta Bureau worked in close cooperation with the American Association for the Promotion of the Teaching of Speech to the Deaf (the AAPTSD) which was organized in 1890, electing Bell as President.

The work of the Bureau increased to such an extent that in 1893 Bell, with the assistance of his father, constructed a neoclassical yellow brick and sandstone building specifically to house the institution.

[12] The building, a neoclassical Corinthian templum in antis structure of closely matching golden yellow sandstone and Roman brick with architectural terracotta details, was built in 1893 to a design by Peabody and Stearns of Boston.

Although Bell self-described his occupation as a "teacher of the deaf" throughout his life, his foremost activities revolved around those of general scientific discovery and invention.

Earlier Bell had met fellow Cambridge resident, Charles Sumner Tainter, a young self-educated instrument maker who had been assigned to the U.S.

In conducting our work we had first to design an experimental apparatus, then hunt about, often in Philadelphia and New York, for the materials with which to construct it, which were usually hard to find, and finally build the models we needed, ourselves.

Tainter's unpublished manuscript and notes (later donated to the Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History)[24] depict Bell as the person who suggested the basic lines of research, furnished the financial resources, and then allowed his associates to receive the credit for many of the inventions that resulted.

On April 1, 1880, and also described by plaque as occurring on June 3, Bell's assistant transmitted the world's first wireless telephone message to him on their newly invented form of telecommunication, the far advanced precursor to fiber-optic communications.

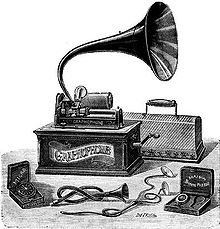

This material described in detail the strange creations and even stranger experiments at the laboratory which led to the greatly improved phonographs in 1886 that were to help found the recording and dictation machine industries.

However, he did not work to improve its quality, likely because of an agreement to spend the next five years developing the New York City electric light and power system.

[35] But Hubbard's phonograph company was quickly threatened with financial disaster because people would not buy a machine that seldom worked and which was also difficult for the average person to operate.

When it was played, a voice from the distant past spoke, reciting a quotation from Shakespeare's Hamlet:[36][37][38] "There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio, than are dreamed of in your philosophy ..." and also, whimsically: "I am a Graphophone and my mother was a Phonograph."

Tainter had previously recorded, on July 7, 1881: "This evening about 7 P.M. ... the apparatus being ready the valve upon the top of the air cylinder was opened slightly until a pressure of about 100 lbs.

The playing arm is rigid except for a pivoted vertical motion of 90 degrees to allow removal of the record or a return to the starting position.

The Volta associates had been experimenting with both types as early as 1881, as is shown by the following quotation from Tainter:[39] The record on the electro-type in the Smithsonian package is of the other form, where the vibrations are impressed parallel to the surface of the recording material, as was done in the old Scott Phonautograph of 1857, thus forming a groove of uniform depth, but of wavy character, in which the sides of the groove act upon the tracing point instead of the bottom, as is the case in the vertical type.

[25][40] At each step of their inventive process the Associates also sought out the best type of materials available in order to produce the clearest and most audible sound reproduction.

[43] The Graphophone designs initially deployed foot treadles to rotate the recordings which were then replaced by more convenient wind-up clockwork drive mechanisms and which finally migrated to electric motors, instead of the manual crank that was used on Edison's phonograph.

The tape passed from one eight inch (20.3 cm) diameter reel and around a pulley with guide flanges, where it came into contact with either the recording or playback stylus.

The tapes, when later examined at one of the Smithsonian Institution's depositories, had become brittle, the heavy paper reels had warped, and the machine's playback head was missing.

It was formed to control the patents and to handle the commercial development of their numerous sound recording and reproduction inventions, one of which became the first dictation machine, the 'Dictaphone'.

[25] After the Volta Associates gave several demonstrations in the City of Washington, businessmen from Philadelphia created the American Graphophone Company on March 28, 1887, in order to produce the machines for the budding phonograph marketplace.

[4][16] Bell's portion of the share exchange at that time had an approximate value of US$200,000 (half of the total received by all of the Associates), $100,000 of which he soon dedicated to the newly formed Volta Bureau's research and pedagogical programs for the deaf.

Tainter resided there for several months to supervise manufacturing before becoming seriously ill, but later went on to continue his inventive work for many years, as health permitted.

The small Bridgeport plant which in its early times was able to produce three or four machines daily later became, as a successor firm, the Dictaphone Corporation.

But it would take several more years and the renewed efforts of Thomas Edison and the further improvements of Emile Berliner, and many others, before the recording industry became a major factor in home entertainment.

His scientific and statistical research work on deafness became so extensive that within a few years his documentation had engulfed an entire room of the Volta Laboratory in his father's backyard carriage house.

Due to the limited space available there, and with the assistance of his father who contributed US$15,000 (approximately $510,000 in today's dollars), [7] Bell had the new Volta Bureau building constructed nearby in 1893.

Museum staff working with scientists at the U.S. Department of Energy's Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory had also revived the voice of his father, Alexander Melville Bell, from an 1881 recording in the wax-filled groove of a modified Edison tinfoil cylinder phonograph.