Voltaire

[47] Voltaire circulated throughout English high society, meeting Alexander Pope, John Gay, Jonathan Swift, Lady Mary Wortley Montagu, Sarah, Duchess of Marlborough, and many other members of the nobility and royalty.

[24][69] Voltaire's own book Elements of the Philosophy of Newton made the great scientist accessible to a far greater public, and the Marquise wrote a celebratory review in the Journal des savants.

It was followed by La Henriade, an epic poem on the French King Henri IV, glorifying his attempt to end the Catholic-Protestant massacres with the Edict of Nantes, which established religious toleration.

He would stay in Ferney for most of the remaining 20 years of his life, frequently entertaining distinguished guests, such as James Boswell (who recorded their conversations in his journal and memoranda),[101] Adam Smith, Giacomo Casanova, and Edward Gibbon.

"[109] Because of his well-known criticism of the Church, which he had refused to retract before his death, Voltaire was denied a Christian burial in Paris,[110] but friends and relations managed to bury his body secretly at the Abbey of Scellières [fr] in Champagne, where Marie Louise's brother was abbé.

Not only did he reject traditional biographies and accounts that claim the work of supernatural forces, but he went so far as to suggest that earlier historiography was rife with falsified evidence and required new investigations at the source.

Voltaire's histories imposed the values of the Enlightenment on the past, but at the same time he helped free historiography from antiquarianism, Eurocentrism, religious intolerance and a concentration on great men, diplomacy, and warfare.

[118][119] Yale professor Peter Gay says Voltaire wrote "very good history", citing his "scrupulous concern for truths", "careful sifting of evidence", "intelligent selection of what is important", "keen sense of drama", and "grasp of the fact that a whole civilization is a unit of study".

[citation needed] The Henriade was written in imitation of Virgil, using the alexandrine couplet reformed and rendered monotonous for modern readers but it was a huge success in the 18th and early 19th century, with sixty-five editions and translations into several languages.

L'Homme aux quarante ecus (The Man of Forty Pieces of Silver) addresses social and political ways of the time; Zadig and others, the received forms of moral and metaphysical orthodoxy; and some were written to deride the Bible.

In pure literary criticism his principal work is the Commentaire sur Corneille, although he wrote many more similar works—sometimes (as in his Life and Notices of Molière) independently and sometimes as part of his Siècles.

Then, in his Dictionnaire philosophique, containing such articles as "Abraham", "Genesis", "Church Council", he wrote about what he perceived as the human origins of dogmas and beliefs, as well as inhuman behavior of religious and political institutions in shedding blood over the quarrels of competing sects.

Although influenced by Socinian works such as the Bibliotheca Fratrum Polonorum, Voltaire's skeptical attitude to the Bible separated him from Unitarian theologians like Fausto Sozzini or even Biblical-political writers like John Locke.

He wrote: "Perhaps there is nothing greater on earth than the sacrifice of youth and beauty, often of high birth, made by the gentle sex in order to work in hospitals for the relief of human misery, the sight of which is so revolting to our delicacy.

[169] In a 1740 letter to Frederick the Great, Voltaire ascribes to Muhammad a brutality that "is assuredly nothing any man can excuse" and suggests that his following stemmed from superstition; Voltaire continued, "But that a camel-merchant should stir up insurrection in his village; that in league with some miserable followers he persuades them that he talks with the angel Gabriel; that he boasts of having been carried to heaven, where he received in part this unintelligible book, each page of which makes common sense shudder; that, to pay homage to this book, he delivers his country to iron and flame; that he cuts the throats of fathers and kidnaps daughters; that he gives to the defeated the choice of his religion or death: this is assuredly nothing any man can excuse, at least if he was not born a Turk, or if superstition has not extinguished all natural light in him.

[e] Drawing on complementary information in Herbelot's "Oriental Library", Voltaire, according to René Pomeau, adjudged the Quran, with its "contradictions, ... absurdities, ... anachronisms", to be "rhapsody, without connection, without order, and without art".

It must be admitted that he removed almost all of Asia from idolatry" and that "it was difficult for such a simple and wise religion, taught by a man who was constantly victorious, could hardly fail to subjugate a portion of the earth."

Voltaire wrote: "Your holiness will pardon the liberty taken by one of the lowest of the faithful, though a zealous admirer of virtue, of submitting to the head of the true religion this performance, written in opposition to the founder of a false and barbarous sect.

[211] He used the antiquity of Hinduism to land what he saw as a devastating blow to the Bible's claims and acknowledged that the Hindus' treatment of animals showed a shaming alternative to the immorality of European imperialists.

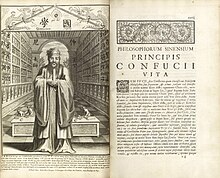

[218] Confucius has no interest in falsehood; he did not pretend to be prophet; he claimed no inspiration; he taught no new religion; he used no delusions; flattered not the emperor under whom he lived...With the translation of Confucian texts during the Enlightenment, the concept of a meritocracy reached intellectuals in the West, who saw it as an alternative to the traditional Ancien Régime of Europe.

[223] Other historians, instead, have suggested that Voltaire's support for polygenism was more heavily encouraged by his investments in the French Compagnie des Indes and other colonial enterprises that engaged in the slave trade.

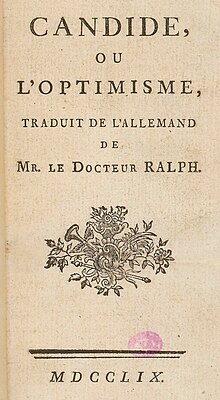

[224][225][226] His most famous remark on slavery is found in Candide, where the hero is horrified to learn "at what price we eat sugar in Europe" after coming across a slave in French Guiana who has been mutilated for escaping, who opines that, if all human beings have common origins as the Bible taught, it makes them cousins, concluding that "no one could treat their relatives more horribly".

I shall say as much to Sophocles and Euripides; I shall speak to Thucydides of your histories, to Quintus Curtius of your Charles XII; and perhaps I shall be stoned by these jealous dead because a single man has united all their different merits in himself.

"[248] Frederick the Great noted the significance of a philosopher capable of influencing judges to change their unjust decisions, commenting that this alone is sufficient to ensure the prominence of Voltaire as a humanitarian.

[267] Voltaire long thought only an enlightened monarch could bring about change, given the social structures of the time and the extremely high rates of illiteracy, and that it was in the king's rational interest to improve the education and welfare of his subjects.

[269] Voltaire is also known for many memorable aphorisms, such as "Si Dieu n'existait pas, il faudrait l'inventer" ("If God did not exist, it would be necessary to invent him"), contained in a verse epistle from 1768, addressed to the anonymous author of a controversial work on The Three Impostors.

The Scottish Victorian writer Thomas Carlyle argued that "Voltaire read history, not with the eye of devout seer or even critic, but through a pair of mere anti-catholic spectacles.

[283] Among them are: Yet...he never for a moment supposed that in this "splendid outburst" all France would accept enthusiastically the philosophy of this queer Jean-Jacques Rousseau who, from Geneva and Paris, was thrilling the world with sentimental romances and revolutionary pamphlets.

Nietzsche speaks of "la gaya scienza, the light feet, wit, fire, grace, strong logic, arrogant intellectuality, the dance of the stars"—surely he was thinking of Voltaire.

Now beside Voltaire put Rousseau: all heat and fantasy, a man with noble and jejune visions, the idol of la bourgeois gentile-femme, announcing like Pascal that the heart has its reason which the head can never understand.