Volunteer Force (New Zealand)

The force provided the bulk of New Zealand's defence during the late nineteenth century and was made up of small independent corps of less than 100 men.

Throughout its entire existence, the Volunteer Force was criticised for being untrained, disorganised and poorly led, with units often prioritising dress uniforms over actual military training.

Many of the modern day units of the New Zealand Army can draw their lineages back to corps of the Volunteer Force.

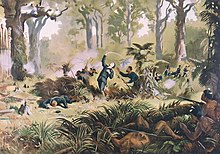

During the 1830s and 1840s, European settlers formed a number of volunteer units throughout the North Island and in Nelson in response to the fear of attack by local Māori.

The Militia could only be utilised within 25 miles of their local police station and were intended to supplement the regular British forces in an emergency.

In 1864 the New Zealand government adopted a self reliance policy which was intended to put more dependence on local militia and friendly Māori.

Each corps could define its own rules concerning civil affairs, financial matters, the admission of members and could even elect their own officers.

[1][8][9] Both the unit allowance and the land price remission was reliant on volunteers being "efficient" (i.e. suitably trained and able to perform their duties).

[8] Each corps was required to maintain a minimum membership or face being disbanded, likewise an upper limit on size was also applied.

[11][12] The Volunteer Force was relatively inactive during the 1870s and was only occasionally utilised for civil matters such as dealing with public disorder, fighting fires and providing a lifeboat service.

In 1873 The Daily Southern Cross published a report that the Russian Cruiser Kaskowiski (cask of whisky) had sailed into Auckland harbour and seized gold and hostages.

He proposed the formation of larger naval brigades to man the costal fortifications and the implementation of a more rigorous training regime.

[19] Whitmore introduced a higher level organisation of Volunteer Force and, between 1885 and 1887, grouped the individual corps together into administrative infantry battalions and mounted regiments.

New Zealand was in the midst of an economic depression and in 1887 the Government invited Major General Henry Schaw to review the colony's defence, with a focus on reducing expenditure as much as possible.

Schaw determined that as the Māori were no longer a threat, internal defence was unnecessary and efforts should be focused on costal protection.

Fox proposed large scale disbandment of inefficient corps, and the dismissal of around a quarter of the officers, who he considered "indifferent or bad".

The 14 military districts were reduced to five (Auckland, Wellington, Canterbury, Otago and Nelson-Westland) and the corps were once again organised into administrative battalions and regiments.

At the Imperial Defence Conference of 1909, Prime Minister Joseph Ward agreed that in the event of war New Zealand would provide an expeditionary force of units organised along the same lines as the British Army.

The Volunteer Force was not compatible with this commitment and upon Ward's return to New Zealand, the Defence Act 1909 was presented to parliament and passed in two weeks.

[1][24] The Defence Act 1909 reorganised the country into four military districts, each with, among other support units, three mounted rifle regiments, four Infantry battalions and a brigade of artillery.

Only the reenlistment dates under the 1865 Volunteer Force Act were considered and this was meet with discontent by some units which claimed to have a longer lineage.