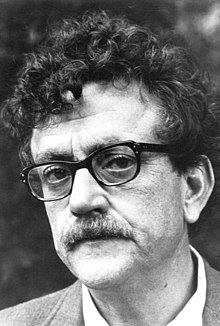

Kurt Vonnegut

[3] Vonnegut's mother was born into Indianapolis's Gilded Age high society, as her family, the Liebers, were among the wealthiest in the city based on a fortune deriving from a successful brewery.

[5][6] Vonnegut later credited Ida Young, his family's African-American cook and housekeeper during the first decade of his life, for raising him and giving him values; he said, "she gave me decent moral instruction and was exceedingly nice to me", and "was as great an influence on me as anybody".

[13] In early 1944, the ASTP was canceled due to the Army's need for soldiers to support the D-Day invasion, and Vonnegut was ordered to an infantry battalion at Camp Atterbury, south of Indianapolis in Edinburgh, Indiana, where he trained as a scout.

[41] Shortly thereafter, General Electric (GE) hired Vonnegut as a technical writer, then publicist,[42] for the company's Schenectady, New York, News Bureau, a publicity department that operated like a newsroom.

[53] Player Piano expresses Vonnegut's opposition to McCarthyism, something made clear when the Ghost Shirts, the revolutionary organization Paul penetrates and eventually leads, is referred to by one character as "fellow travelers".

[53] The New York Times writer and critic Granville Hicks gave Player Piano a positive review, favorably comparing it to Aldous Huxley's Brave New World.

"[60] William Rodney Allen, in his guide to Vonnegut's works, stated that Rumfoord foreshadowed the fictional political figures who would play major roles in God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater and Jailbird.

Howard W. Campbell Jr., Vonnegut's protagonist, is an American who is raised in Germany from age 11 and joins the Nazi Party during the war as a double agent for the US Office of Strategic Services, rising to the regime's highest ranks as a radio propagandist.

[63] Also published in 1961 was Vonnegut's short story "Harrison Bergeron", set in a dystopic future where all are equal, even if that means disfiguring beautiful people and forcing the strong or intelligent to wear devices that negate their advantages.

Eliot Rosewater, the wealthy son of a Republican senator, seeks to atone for his wartime killing of noncombatant firefighters by serving in a volunteer fire department and by giving away money to those in trouble or need.

[70] Allen deemed God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater more "a cry from the heart than a novel under its author's full intellectual control", that reflected family and emotional stresses Vonnegut was going through at the time.

In 1999, he wrote in The New York Times: "I had gone broke, was out of print and had a lot of kids..." But then, on the recommendation of an admirer, he received a surprise offer of a teaching job at the Iowa Writers' Workshop, employment that he likened to the rescue of a drowning man.

He was hailed as a hero of the burgeoning anti-war movement in the United States, was invited to speak at numerous rallies, and gave college commencement addresses around the country.

[80] In addition to briefly teaching at Harvard University as a lecturer in creative writing in 1970, Vonnegut taught at the City College of New York as a distinguished professor during the 1973–1974 academic year.

Vonnegut's difficulties in his personal life thereafter materialized in numerous ways, including the painfully slow progress made on his next novel, the darkly comical Breakfast of Champions.

In Thomas S. Hischak's book American Literature on Stage and Screen, Breakfast of Champions was called "funny and outlandish", but reviewers noted that it "lacks substance and seems to be an exercise in literary playfulness".

[82] In subsequent years, his popularity resurged as he published several satirical books, including Jailbird (1979), Deadeye Dick (1982), Galápagos (1985), Bluebeard (1987), and Hocus Pocus (1990).

He could easily have become a crank, but he was too smart; he could have become a cynic, but there was something tender in his nature that he could never quite suppress; he could have become a bore, but even at his most despairing he had an endless willingness to entertain his readers: with drawings, jokes, sex, bizarre plot twists, science fiction, whatever it took.

In a 2006 Rolling Stone interview, Vonnegut sardonically stated that he would sue the Brown & Williamson tobacco company, the maker of the Pall Mall-branded cigarettes he had been smoking since he was around 12 or 14 years old, for false advertising: "And do you know why?

[92] When asked about the impact Vonnegut had on his work, author Josip Novakovich stated that he has "much to learn from Vonnegut—how to compress things and yet not compromise them, how to digress into history, quote from various historical accounts, and not stifle the narrative.

"[100] Donald E. Morse notes that Vonnegut "is now firmly, if somewhat controversially, ensconced in the American and world literary canon as well as in high school, college and graduate curricula".

What matters is the attempt, and the recognition that ... we must try to map this unstable and perilous terrain, even if we know in advance that our efforts are doomed.The Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame inducted Vonnegut posthumously in 2015.

One character, Mary O'Hare, opines that "wars were partly encouraged by books and movies", starring "Frank Sinatra or John Wayne or some of those other glamorous, war-loving, dirty old men".

[128] Vonnegut's works are filled with characters founding new faiths,[126] and religion often serves as a major plot device, for example, in Player Piano, The Sirens of Titan and Cat's Cradle.

In his book Popular Contemporary Writers, Michael D. Sharp describes Vonnegut's linguistic style as straightforward, his sentences concise, his language simple, his paragraphs brief, and his ordinary tone conversational.

However, literary theorist Robert Scholes noted in Fabulation and Metafiction that Vonnegut "reject[s] the traditional satirist's faith in the efficacy of satire as a reforming instrument.

The bombastic opening—"All this happened"—"reads like a declaration of complete mimesis," which is radically called into question in the rest of the quote and "[t]his creates an integrated perspective that seeks out extratextual themes [like war and trauma] while thematizing the novel's textuality and inherent constructedness at one and the same time.

[169] In God Bless You, Mr. Rosewater, readers may find it difficult to determine whether the rich or the poor are in worse circumstances, as the lives of both groups' members are ruled by their wealth or their poverty.

Marvin suggests that Vonnegut's works demonstrate what happens when a "hereditary aristocracy" develops, where wealth is inherited along familial lines: the ability of poor Americans to overcome their situations is greatly or completely diminished.

Loss of purpose is also depicted in Galápagos, where a florist rages at her spouse for creating a robot able to do her job, and in Timequake, where an architect kills himself when replaced by computer software.