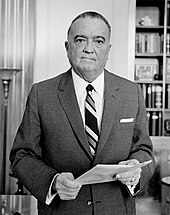

Mark Felt

William Mark Felt Sr. (August 17, 1913 – December 18, 2008) was an American law enforcement officer who worked for the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) from 1942 to 1973 and was known for his role in the Watergate scandal.

In 1980, he was convicted of having violated the civil rights of people thought to be associated with members of the Weather Underground, by ordering FBI agents to break into their homes and search the premises as part of an attempt to prevent bombings.

In 2005, at age 91, Felt revealed to Vanity Fair magazine that during his tenure as Deputy Director of the FBI he had been the anonymous source known as "Deep Throat",[1][2] who provided The Washington Post reporters Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein with critical information about the Watergate scandal, which ultimately led to the resignation of President Richard Nixon in 1974.

He returned to FBI Headquarters, where he was assigned to the Espionage Section of the Domestic Intelligence Division, tracking down spies and saboteurs during World War II.

[21] The Salt Lake City office included Nevada within its purview, and Felt oversaw some of the Bureau's earliest investigations into organized crime, assessing the Mob's operations in the Reno and Las Vegas casinos.

[22]) In February 1958, Felt was assigned to Kansas City, Missouri (which he dubbed "the Siberia of field offices" in his memoir),[20] where he directed further investigations of organized crime.

The lead federal prosecutor on the case, William C. Ibershof, claims that Felt and Attorney General John Mitchell initiated these illegal activities that tainted the investigation.

"[38] Felt wrote in his memoir: The record amply demonstrates that President Nixon made Pat Gray the Acting Director of the FBI because he wanted a politician in J. Edgar Hoover's position who would convert the Bureau into an adjunct of the White House machine.

"[42] In the book, Deep Throat is described as an "incorrigible gossip" who was "in a unique position to observe the Executive Branch", a man "whose fight had been worn out in too many battles".

Woodward was working as an aide to Admiral Thomas Hinman Moorer, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and was delivering papers to the White House Situation Room.

Felt's information, taken on a promise that Woodward would never reveal its origin, was a source for a few stories, notably for an article on May 18, 1972, about Arthur Bremer, who shot George Wallace.

Felt told Woodward on June 19 that E. Howard Hunt, who had connections to Nixon, was involved: the telephone number of his White House office had been listed in the address book of one of the burglars.

[45] Woodward explained that when he wanted to meet Deep Throat, he would move a flowerpot with a red flag on his apartment balcony; he lived at number 617, Webster House, 1718 P Street, Northwest.

Felt said: To not take action against these people and know of a bombing in advance would simply be to stick your fingers in your ears and protect your eardrums when the explosion went off and then start the investigation.Griffin Bell, the Attorney General in the Jimmy Carter administration, directed investigation of these cases.

On April 10, 1978, a federal grand jury charged Felt, Miller, and Gray with conspiracy to violate the constitutional rights of U.S. citizens by searching their homes without warrants.

[68][69] He testified that in authorizing the Bureau to conduct break-ins to gather foreign intelligence information "he was acting on precedents established by a number of Presidential directives dating to 1939."

Also testifying were former Attorneys General Mitchell, Kleindienst, Herbert Brownell Jr., Nicholas Katzenbach, and Ramsey Clark, all of whom said warrantless searches in national security matters were commonplace and understood not to be illegal.

[62][74][75] Writing an OpEd piece in The New York Times a week after the conviction, attorney Roy Cohn claimed that Felt and Miller were being used as scapegoats by the Carter administration and it was an unfair prosecution.

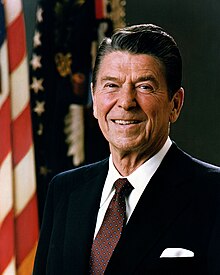

[79][80][81] In the pardon, Reagan wrote: During their long careers, Mark Felt and Edward Miller served the Federal Bureau of Investigation and our nation with great distinction.

Their convictions in the U.S. District Court, on appeal at the time I signed the pardons, grew out of their good-faith belief that their actions were necessary to preserve the security interests of our country.

[88] Felt and his son Mark Jr., an officer in the United States Air Force, decided to keep this a secret and told Joan that her mother had died of a heart attack.

He bought a house where he lived with Joan, and took care of the boys while she worked, teaching at Sonoma State University and Santa Rosa Junior College.

"Woodward just showed up at the door and said he was in the area," Joan Felt was quoted as saying in Kessler's 2002 book: "He came in a white limousine, which parked at a schoolyard about ten blocks away.

"[92] In his memoir, Felt strongly defended Hoover and his tenure as Director; he condemned the criticisms of the Bureau made in the 1970s by the Church Committee and civil libertarians.

(He opens the book with the sentence, "The Bill of Rights is not a suicide pact", Justice Robert H. Jackson's comment in his dissent to Terminiello v. City of Chicago, 337 U.S. 1 (1949)).

[97] On June 25 of that year, a few weeks after All the President's Men was published, The Wall Street Journal ran an editorial, "If You Drink Scotch, Smoke, Read, Maybe You're Deep Throat".

The prosecutor, J. Stanley Pottinger, Assistant Attorney General for Civil Rights, discovered that Felt was "Deep Throat", but the secrecy of the proceedings protected the information from being public.

[101] Alexander P. Butterfield, the White House aide best known for revealing Nixon's taping system, told the Hartford Courant in 1995, "I think it was a guy named Mark Felt.

After the Vanity Fair story broke, Benjamin C. Bradlee on June 1, 2005, the editor of the Washington Post during Watergate, confirmed that Felt was Deep Throat.

[109] A Los Angeles Times editorial argued that this argument was specious, "as if there's no difference between nuclear strategy and rounding up hush money to silence your hired burglars".