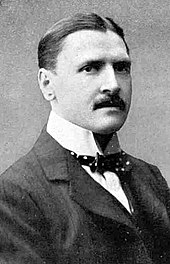

W. Somerset Maugham

More recent assessments generally rank Of Human Bondage – a book with a large autobiographical element – as a masterpiece, and his short stories are widely held in high critical regard.

[16][n 4] From 1885 to 1890 Maugham attended The King's School, Canterbury, where he was regarded as an outsider and teased for his poor English (French had been his first language), his short stature, his stammer, and his lack of interest in sport.

He wrote near the opening of the novel: "... it is impossible always to give the exact unexpurgated words of Liza and the other personages of the story; the reader is therefore entreated with his thoughts to piece out the necessary imperfections of the dialogue".

The Evening Standard commented that there had not been so powerful a story of slum life since Rudyard Kipling's The Record of Badalia Herodsfoot (1890), and praised the author's "vividness and knowledge ... extraordinary gift of directness and concentration ... His characters have an astounding amount of vitality".

[29] The Westminster Gazette praised the writing but deplored the subject matter,[30] and The Times also conceded the author's skill – "Mr Maugham seems to aspire, and not unsuccessfully, to be the Zola of the New Cut" – but thought him "capable of better things [than] this singularly unpleasant novel".

[34] He based himself in Seville, where he grew a moustache, smoked cigars, took lessons in the guitar,[34] and developed a passion for "a young thing with green eyes and a gay smile"[35] (gender carefully unspecified, as Hastings comments).

The critic John Sutherland says of it: The hero, Philip Carey, suffers the same childhood misfortunes as Maugham himself: the loss of his mother, the breakup of his family home, and his emotionally straitened upbringing by elderly relatives.

Raphael comments that there is no firm evidence for this,[5][53] and Meyers suggests that she is based on Harry Phillips, a young man whom Maugham had taken to Paris as, nominally, his secretary for a prolonged stay in 1905.

[56] The tide of opinion was turned by the influential American novelist and critic Theodore Dreiser, who called Maugham a great artist and the book a work of genius, of the utmost importance, comparable to a Beethoven symphony.

[5][57] Bryan Connon comments in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, "After this it seemed that Maugham could not fail, and the public eagerly bought his novels [and] volumes of his carefully crafted short stories".

[65] Samoa was regarded as crucial to Britain's strategic interests, and Maugham's task was to gather information about the island's powerful radio transmitter and the threat from German military and naval forces in the region.

Maugham wrote of Haxton: He had an amiability of disposition that enabled him in a very short time to make friends with people in ships, clubs, bar-rooms, and hotels, so that through him I was able to get into easy contact with an immense number of persons whom otherwise I should have known only from a distance.

[73] It was well received: reviewers called it "extraordinarily powerful and interesting",[74] and "a triumph [that] has given me such pleasure and entertainment as rarely comes my way";[75] one described it as "an exhibition of the beast in man, done with such perfect art that it is beyond praise".

[n 10] When the Second World War began in 1939 he stayed in his home as long as he could, but in June 1940 France surrendered; knowing himself to be proscribed by the Nazis (Joseph Goebbels denounced him personally) Maugham made his way to England in uncomfortable conditions on a coal freighter from Nice.

[105] His most substantial book from the war years was The Razor's Edge; he found writing it unusually tiring – he was seventy when it was completed – and vowed it would be the last long novel he wrote.

Connon writes, "He was seen by some as a near saint and by others, particularly the Maugham family, as a villain";[5] Hastings labels him "a podgy Iago ... constantly briefing against [Syrie and Liza]", and quotes Alan Pryce-Jones's summary: "an intriguer, a schemer with a keen eye to his own advantage, a troublemaker".

While there, he established and endowed the Somerset Maugham Award, to be administered by the Society of Authors and given annually for a work of fiction, non-fiction, or poetry written by a British subject under the age of thirty-five.

[123] Nonetheless, his final years, according to Connon, were marred by increasing senility, misguided legal disputes and a memoir, published in 1962, Looking Back, in which "he denigrated his late former wife, was dismissive of Haxton, and made a clumsy attempt to deny his homosexuality by claiming he was a red-blooded heterosexual".

A person was "as clever as a bagful of monkeys", the beauty of the heroine "took your breath away", a friend was "a damned good sort", a villain was "an unmitigated scoundrel", a bore "talked your head off", and the hero's heart "beat nineteen to the dozen".

[133]In his 1926 short story "The Creative Impulse" Maugham made fun of self-conscious stylists whose books appealed only to a literary clique: "It was indeed a scandal that so distinguished an author, with an imagination so delicate and a style so exquisite, should remain neglected of the vulgar".

[138] Raphael remarks about Maugham as a playwright, "His wit was sharp but rarely distressing; his plots abounded in amusing situations, his characters were usually drawn from the same class as his audiences and managed at once to satirize and delight their originals".

[142] Christopher Innes has observed that, like Chekhov, Maugham qualified as a doctor, and their medical training gave them "a materialistic determinism that discounted any possibility of changing the human condition".

[149] Liza of Lambeth caused outrage in some quarters, not only because its heroine sleeps with a married man, but also for its graphic depiction of the deprivation and squalor of the London slums, of which most people from Maugham's social class preferred to remain ignorant.

Like Of Human Bondage it has a strong female character at its centre, but the two are polar opposites: the malign Mildred in the earlier novel contrasts with the lovable, and much loved, Rosie in Cakes and Ale.

The Razor's Edge, the author's last major novel,[5] is described by Sutherland as "Maugham's twentieth-century manifesto for human fulfilment", satirising Western materialism and drawing on Eastern spiritualism as a way to find meaning in existence.

His stories – the first in the genre of spy fiction continued by Ian Fleming, John le Carré and many others[169] – are based so closely on Maugham's experiences that it was not until ten years after the war ended that the security services permitted their publication.

[171] Comic stories include "Jane" (1923), about a dowdy widow who reinvents herself as an outrageous and conspicuous society figure, to the consternation of her family;[172] "The Creative Impulse" (1926), in which a domineering authoress is shocked when her mild-mannered husband leaves her and sets up home with their cook;[172] and "The Three Fat Women of Antibes" (1933) in which three middle-aged friends play highly competitive bridge while attempting to slim, until reversals at the bridge table at the hands of an effortlessly slender fourth player provoke them into extravagantly breaking their diets.

[196][n 18] Even an admirer such as Evelyn Waugh felt that Maugham's disciplined writing with its "brilliant technical dexterity" was not without disadvantages: He is never boring or clumsy, he never gives a false impression; he is never shocking; but this very diplomatic polish makes impossible for him any of those sudden transcendent flashes of passion and beauty which less competent novelists occasionally attain.

[202] Marking Maugham's eightieth birthday The New York Times commented that he had not only outlived his contemporaries including Shaw, Joseph Conrad, H. G. Wells, Henry James, Arnold Bennett and John Galsworthy but was now seen to rank with them in excellence, after years in which his popularity had caused critics to depreciate his work.

[158] In 2014 Robert McCrum concluded an article about Of Human Bondage – which he said "shows the author's savage honesty and gift for storytelling at their best": Many would say that his short stories embody his best work, and he remains a substantial figure in the early-20th-century literary landscape.