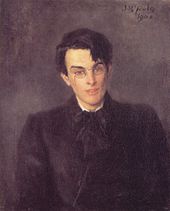

W. B. Yeats

His earliest volume of verse was published in 1889, and its slow-paced, modernist and lyrical poems display debts to Edmund Spenser, Percy Bysshe Shelley and the poets of the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood.

His major works include The Land of Heart's Desire (1894), Cathleen ni Houlihan (1902), Deirdre (1907), The Wild Swans at Coole (1919), The Tower (1928) and Last Poems and Plays (1940).

While his family was supportive of the changes Ireland was experiencing, the nationalist revival of the late 19th century directly disadvantaged his heritage and informed his outlook for the remainder of his life.

[19] Yeats began writing his first works when he was seventeen; these included a poem—heavily influenced by Percy Bysshe Shelley—that describes a magician who set up a throne in central Asia.

Other pieces from this period include a draft of a play about a bishop, a monk, and a woman accused of paganism by local shepherds, as well as love-poems and narrative lyrics on German knights.

[23] Although Yeats's early works drew heavily on Shelley, Edmund Spenser, and on the diction and colouring of pre-Raphaelite verse, he soon turned to Irish mythology and folklore and the writings of William Blake.

[28] In 1892 Yeats wrote: "If I had not made magic my constant study I could not have written a single word of my Blake book, nor would The Countess Kathleen ever have come to exist.

[32] During séances held from 1912, a spirit calling itself "Leo Africanus" apparently claimed it was Yeats's Daemon or anti-self, inspiring some of the speculations in Per Amica Silentia Lunae.

"The Wanderings of Oisin" is based on the lyrics of the Fenian Cycle of Irish mythology and displays the influence of both Sir Samuel Ferguson and the Pre-Raphaelite poets.

[36] In 1890 Yeats and Ernest Rhys co-founded the Rhymers' Club,[37] a group of London-based poets who met regularly in a Fleet Street tavern to recite their verse.

[42] In later years he admitted, "it seems to me that she [Gonne] brought into my life those days—for as yet I saw only what lay upon the surface—the middle of the tint, a sound as of a Burmese gong, an over-powering tumult that had yet many pleasant secondary notes.

Together with Lady Gregory, Martyn, and other writers including J. M. Synge, Seán O'Casey, and Padraic Colum, Yeats was one of those responsible for the establishment of the "Irish Literary Revival" movement.

[52] Apart from these creative writers, much of the impetus for the Revival came from the work of scholarly translators who were aiding in the discovery of both the ancient sagas and Ossianic poetry and the more recent folk song tradition in Irish.

"[54][55] The group's manifesto, which Yeats wrote, declared, "We hope to find in Ireland an uncorrupted & imaginative audience trained to listen by its passion for oratory ... & that freedom to experiment which is not found in the theatres of England, & without which no new movement in art or literature can succeed.

A more indirect influence was the scholarship on Japanese Noh plays that Pound had obtained from Ernest Fenollosa's widow, which provided Yeats with a model for the aristocratic drama he intended to write.

In the preface of the latter, he wrote: "One must not expect in these stories the epic lineaments, the many incidents, woven into one great event of, let us say the War for the Brown Bull of Cuailgne or that of the last gathering at Muirthemne.

[70] Gonne's history of revolutionary political activism, as well as a series of personal catastrophes in the previous few years of her life—including chloroform addiction and her troubled marriage to MacBride—made her a potentially unsuitable wife;[45] biographer R. F. Foster has observed that Yeats's last offer was motivated more by a sense of duty than by a genuine desire to marry her.

His reply to many of the letters of congratulations sent to him contained the words: "I consider that this honour has come to me less as an individual than as a representative of Irish literature, it is part of Europe's welcome to the Free State.

[79][80] Early in his tenure, a debate on divorce arose, and Yeats viewed the issue as primarily a confrontation between the emerging Roman Catholic ethos and the Protestant minority.

[81] When the Roman Catholic Church weighed in with a blanket refusal to consider their anti position, The Irish Times countered that a measure to outlaw divorce would alienate Protestants and "crystallise" the partition of Ireland.

In response, Yeats delivered a series of speeches that attacked the "quixotically impressive" ambitions of the government and clergy, likening their campaign tactics to those of "medieval Spain.

This conviction has come to us through ancient philosophy and modern literature, and it seems to us a most sacrilegious thing to persuade two people who hate each other... to live together, and it is to us no remedy to permit them to part if neither can re-marry.

[83] His language became more forceful; the Jesuit Father Peter Finlay was described by Yeats as a man of "monstrous discourtesy", and he lamented that "It is one of the glories of the Church in which I was born that we have put our Bishops in their place in discussions requiring legislation.

Aware of the symbolic power latent in the imagery of a young state's currency, he sought a form that was "elegant, racy of the soil, and utterly unpolitical".

[89] During this time, Yeats was involved in a number of romantic affairs with, among others, the poet and actress Margot Ruddock and the novelist, journalist and sexual radical Ethel Mannin.

'"[95] In September 1948, Yeats's body was moved to the churchyard of St Columba's Church, Drumcliff, County Sligo, on the Irish Naval Service corvette LÉ Macha.

Neither Michael Yeats nor Sean MacBride, the Irish foreign minister who organised the ceremony, wanted to know the details of how the remains were collected, Ostrorog notes.

[108] While Yeats's early poetry drew heavily on Irish myth and folklore, his later work was engaged with more contemporary issues, and his style underwent a dramatic transformation.

[111] Critics characterize his middle work as supple and muscular in its rhythms and sometimes harshly modernist, while others find the poems barren and weak in imaginative power.

[114] Yeats's mystical inclinations, informed by Hinduism, theosophical beliefs and the occult, provided much of the basis of his late poetry,[115] which some critics have judged as lacking in intellectual credibility.