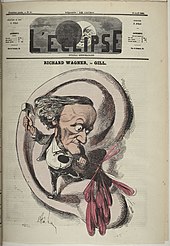

Richard Wagner

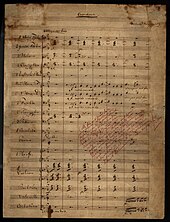

Wagner's compositions, particularly those of his later period, are notable for their complex textures, rich harmonies and orchestration, and the elaborate use of leitmotifs—musical phrases associated with individual characters, places, ideas, or plot elements.

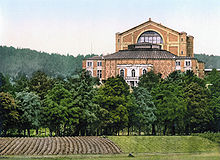

To properly present his vision of the works, Wagner had his own opera house built to his specifications: the Bayreuth Festspielhaus, which featured many innovative design elements intended to immerse the audience in the drama.

Declared a "genius" by some and a "disease" by others, his music is widely performed, but his views on religion, politics, and social life are debated—most notably on the extent to which his antisemitism finds expression in his stage and prose works.

In Mein Leben Wagner wrote, "When I look back across my entire life I find no event to place beside this in the impression it produced on me," and claimed that the "profoundly human and ecstatic performance of this incomparable artist" kindled in him an "almost demonic fire".

[28][29] Wagner had fallen for one of the leading ladies at Magdeburg, the actress Christine Wilhelmine "Minna" Planer,[30] and after the disaster of Das Liebesverbot he followed her to Königsberg, where she helped him to get an engagement at the theatre.

[37] Initially the pair took a stormy sea passage to London,[38] from which Wagner drew the inspiration for his opera Der fliegende Holländer (The Flying Dutchman), with a plot based on a sketch by Heinrich Heine.

Wagner made a scant living by writing articles and short novelettes such as A pilgrimage to Beethoven, which sketched his growing concept of "music drama", and An end in Paris, where he depicts his own miseries as a German musician in the French metropolis.

His relief at returning to Germany was recorded in his "Autobiographic Sketch" of 1842, where he wrote that, en route from Paris, "For the first time I saw the Rhine—with hot tears in my eyes, I, poor artist, swore eternal fidelity to my German fatherland.

Wagner was active among socialist German nationalists there, regularly receiving such guests as the conductor and radical editor August Röckel and the Russian anarchist Mikhail Bakunin.

According to Wagner, Jews such as Meyerbeer commercialised music catered to the masses in order to achieve fame and financial success, rather than creating genuine works of art.

[100] Wagner noted that his rescue by Ludwig coincided with news of the death of his earlier mentor (but later supposed enemy) Giacomo Meyerbeer, and regretted that "this operatic master, who had done me so much harm, should not have lived to see this day.

[132] The festival firmly established Wagner as an artist of European, and indeed world, importance: attendees included Kaiser Wilhelm I, the Emperor Pedro II of Brazil, Anton Bruckner, Camille Saint-Saëns and Pyotr Ilyich Tchaikovsky.

He was once again assisted by the liberality of King Ludwig, but was still forced by his personal financial situation in 1877 to sell the rights of several of his unpublished works (including the Siegfried Idyll) to the publisher Schott.

[147] The legend that the attack was prompted by an argument with Cosima over Wagner's supposedly amorous interest in the singer Carrie Pringle, who had been a Flower-maiden in Parsifal at Bayreuth, is without credible evidence.

The orchestra's dramatic role in the later operas includes the use of leitmotifs, musical phrases that can be interpreted as announcing specific characters, locales, and plot elements; their complex interweaving and evolution illuminate the progression of the drama.

[158] The compositional style of these early works was conventional—the relatively more sophisticated Rienzi showing the clear influence of Grand Opera à la Spontini and Meyerbeer—and did not exhibit the innovations that would mark Wagner's place in musical history.

[177] Millington describes Meistersinger as "a rich, perceptive music drama widely admired for its warm humanity",[178] but its strong German nationalist overtones have led some to cite it as an example of Wagner's reactionary politics and antisemitism.

[179] When Wagner returned to writing the music for the last act of Siegfried and for Götterdämmerung (Twilight of the Gods) as the final part of the Ring, his style had changed once more to something more recognisable as "operatic" than the aural world of Rheingold and Walküre, though it was still thoroughly stamped with his own originality as a composer and suffused with leitmotifs.

Wagner's final opera, Parsifal (1882), which was his only work written especially for his Bayreuth Festspielhaus and which is described in the score as a "Bühnenweihfestspiel" ("festival play for the consecration of the stage"), has a storyline suggested by elements of the legend of the Holy Grail.

[n 20] More rarely performed are the American Centennial March (1876), and Das Liebesmahl der Apostel (The Love Feast of the Apostles), a piece for male choruses and orchestra composed in 1843 for the city of Dresden.

Notably from Tristan und Isolde onwards, he explored the limits of the traditional tonal system, which gave keys and chords their identity, pointing the way to atonality in the 20th century.

Anton Bruckner and Hugo Wolf were greatly indebted to him, as were César Franck, Henri Duparc, Ernest Chausson, Jules Massenet, Richard Strauss, Alexander von Zemlinsky, Hans Pfitzner and many others.

[217] Among those from the late 20th century and beyond claiming inspiration from Wagner's music are the German band Rammstein;[218] Jim Steinman, who wrote songs for Meat Loaf, Bonnie Tyler, Air Supply, Celine Dion and others;[219] and the electronic composer Klaus Schulze, whose 1975 album Timewind consists of two 30-minute tracks, "Bayreuth Return" and "Wahnfried 1883".

Millington has commented:[Wagner's] protean abundance meant that he could inspire the use of literary motif in many a novel employing interior monologue; ... the Symbolists saw him as a mystic hierophant; the Decadents found many a frisson in his work.

[226] Édouard Dujardin, whose influential novel Les Lauriers sont coupés is in the form of an interior monologue inspired by Wagnerian music, founded a journal dedicated to Wagner, La Revue wagnérienne, to which J. K. Huysmans and Téodor de Wyzewa contributed.

[227] In a list of major cultural figures influenced by Wagner, Bryan Magee includes D. H. Lawrence, Aubrey Beardsley, Romain Rolland, Gérard de Nerval, Pierre-Auguste Renoir, Rainer Maria Rilke and several others.

[234] Wagner had publicly analysed the Oedipus myth before Freud was born in terms of its psychological significance, insisting that incestuous desires are natural and normal, and perceptively exhibiting the relationship between sexuality and anxiety.

[264] Other biographers (such as Lucy Beckett) believe that this is not true, as the original drafts of the story date back to 1857 and Wagner had completed the libretto for Parsifal by 1877,[265] but he displayed no significant public interest in Gobineau until 1880.

Thus, for example, George Bernard Shaw wrote in The Perfect Wagnerite (1883): [Wagner's] picture of Niblunghome[n 24] under the reign of Alberic is a poetic vision of unregulated industrial capitalism as it was made known in Germany in the middle of the 19th century by Engels's book The Condition of the Working Class in England.

"[270] The writer Robert Donington has produced a detailed, if controversial, Jungian interpretation of the Ring cycle, described as "an approach to Wagner by way of his symbols", which, for example, sees the character of the goddess Fricka as part of her husband Wotan's "inner femininity".