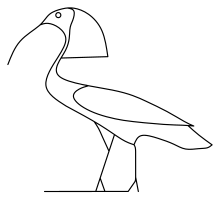

Northern bald ibis

It breeds colonially on coastal or mountain cliff ledges, where it typically lays two to three eggs in a stick nest, and feeds on lizards, insects, and other small animals.

To combat these low numbers, reintroduction programs have been instituted internationally in recent times, with a semi-wild breeding colony in Turkey which counted almost 250 birds in 2018[3] as well as sites in Austria, Italy, Spain, and northern Morocco.

[7][8] The northern bald ibis was described and illustrated by Swiss naturalist Conrad Gesner in his Historiae animalium in 1555,[10][11] and given the binomial name Upupa eremita by Carl Linnaeus in his 1758 Systema Naturae.

The alternative common name Waldrapp is German for forest raven, the equivalent of the Latin Corvo sylvatico of Gesner,[10] adapted as Corvus sylvaticus by Linnaeus.

[22] Unlike many other ibises, which nest in trees and feed in wetlands, the northern bald ibis breeds on undisturbed cliff ledges, and forages for food in irregularly cultivated, grazed dry areas such as semi-arid steppes, and fallow fields.

[27] It bred along the Danube and Rhone Rivers, and in the mountains of Spain, Italy, Germany, Austria and Switzerland (Gesner's original description was of a Swiss bird),[28] and most probably also in the Upper Adriatic region.

[35] Intensive field surveys in spring 2002, based on the knowledge of Bedouin nomads and local hunters, revealed that the species had never become completely extinct on the Syrian desert steppes.

[1] In the rest of its former range, away from the Moroccan coastal locations, the northern bald ibis migrated south for the winter, and formerly occurred as a vagrant to Spain, Iraq, Egypt, the Azores, and Cape Verde.

[33][39] The northern bald ibis breeds in loosely spaced colonies, nesting on cliff ledges or amongst boulders on steep slopes, usually on the coast or near a river.

[25] The northern bald ibis consumes a very wide variety of mainly animal food; faecal analysis of the Moroccan breeding population has shown that lizards and tenebrionid beetles predominate in the diet,[25] although small mammals, ground-nesting birds, and invertebrates such as snails, scorpions, spiders, and caterpillars are also taken.

These include significant human persecution, especially hunting, and also the loss of steppe and non-intensive agricultural areas (particularly in Morocco), pesticide poisoning, disturbance, and dam construction.

Although the cause of death was initially thought to have been from poison, probably laid by chicken farmers to kill rodents, the autopsy revealed that they had actually been electrocuted whilst standing on electricity pylons.

[50] Monitoring of Moroccan wild population is guaranteed by BirdLife International partners, especially by RSPB, SEO/BirdLife and, recently GREPOM in cooperation with Souss-Massa National Park administration[51] and the support of institutions like Prince Albert II of Monaco Foundation[52] which is the Species Champion[53] for Northern Bald Ibis.

Quantitative assessments of the importance of sites for breeding, roosting, and foraging have guided actions to prevent disturbance and the loss of key areas to mass tourism development.

The provision of drinking water and the removal and deterrence of predators and competitors enhances breeding prospects, and monitoring has confirmed that steppe and two-year fallows are key feeding habitats.

[56] Maintaining such non-intensive land uses in the future may present major management challenges, and the recovery in the Souss-Massa region remains precarious because the population is concentrated in just a few places.

[41] The main cause of breeding failure at the Souss-Massa National Park is the loss of eggs to predators,[1] especially the common raven which nest monitoring has shown to have had a serious impact at one sub-colony.

[25] The effects of predators on adult birds have not been studied, but the very similar southern bald ibis, Geronticus calvus, is hunted by large raptors, particularly those that share its breeding cliffs.

[25] Conservation efforts for the northern bald ibis in Syria began with the discovery of an unreported relict colony of this species in early 2002 in the Palmyra desert.

[15] The bald ibises still breeding in Syria, discovered during an extensive biodiversity survey carried out as part of a FAO cooperation project, are the last living descendants of those depicted in Egyptian hieroglyphs from 4500 years ago.

[59] Thanks to an IUCN project the Ibis Protected Area in Palmyra desert was further developed in 2008–2009, addressing the threats of infrastructure proliferation and oil company heavy prospection schemes.

[60] With the loss of the genuinely wild Turkish population, the Ministry of Environment and Forestry's Directorate of Natural Preservation and National Parks established a new semi-wild colony at Birecik.

[46][63] Decisions taken at the meeting included:[63] A second conference in Spain in 2006 stressed the need to survey potential and former sites in north-west Africa and the Middle East for currently undetected colonies.

After learning to follow their human foster-mothers seated in ultralight aircraft, around 30 young birds are led over the Alps to spend the winter months in Tuscany.

[79] Proyecto Eremita is a Spanish reintroduction involving the release of nearly 30 birds in the Ministry of Defence training ground in La Janda district, Barbate, Cádiz Province.

[88] According to local legend in the Birecik area, the northern bald ibis was one of the first birds that Noah released from the Ark as a symbol of fertility,[70] and a lingering religious sentiment in Turkey helped the colonies there to survive long after the demise of the species in Europe, as described above.

[70] The bird painted in 1490 in one of the Gothic frescoes in the Holy Trinity Church in Hrastovlje (now southwestern Slovenia) in the Karst by John of Kastav was most probably the northern bald ibis.

[29] A small illustration of the northern bald ibis is found in the illuminated St Galler Handschrift of 1562,[95] a drawing by Joris Hoefnagel in Missale Romanum (1582-1590) and in paintings in the collection of Rudolf II at Vienna.

[27] It is believed that it had also been depicted at other places in Istria and Dalmatia, where it was presumably native during the Middle Ages, e.g. in the local church in Gradišče pri Divači and in the coat of arms of the noble family Elio from Koper.

They include Algeria, Morocco, Sudan, Syria, Turkey, and Yemen, which are breeding or migration locations; Austria, which is seeking to reintroduce the bird; and Jersey,[98] which has a small captive population.

— Birds from Birecik visited the Syrian colony at Palmyra. [ 34 ]