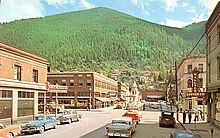

Wallace, Idaho

[citation needed] In the spring of 1884, Colonel William R. Wallace built a cabin at a site he called "Placer Center."

Wallace believed in his new venture and invested money to build access roads, put up lot fences and make other improvements.

[10][11] The settlement flourished, and by the fall of 1887 when its first school was opened, there were many saloons, one brewery, a large apartment building with a public hall, a hotel, and many stores and shops.

[8] In November 1888, the townsite company engaged a Washington, D.C., attorney who specialized in contested public lands cases.

The Department of Interior (DOI) denied a Montana land claim because the scrip had been used for the benefit of persons other than the mixed-blood it had been issued to initially.

This decision more closely followed the apparent intent of the original legislation, but was actually a reversal of long-standing GLO practice.

One group of speculators made substantial profits from at least 15,000 acres (6,070 ha) of land in Minnesota, Nevada and California.

[9] In Wallace, the news of the case led many townspeople—on the night of Tuesday, February 19, 1889—to participate in "lot jumping," that is, peremptorily marking the space as their own.

"[9] William R. Wallace reacted to the jumping with an angry letter, partially quoted above to describe what the company considered improper action by the GLO.

[15] Continuing their aggressive stance, the Wallace Townsite Company filed 13 legal suits, demanding $1,000 from citizens it claimed had illegally jumped their properties.

By the time the disputes were concluded, William R. Wallace had opened an office in Spokane to pursue mining ventures in the West.

[16][17][6] In July 1890, a fire aided by strong winds destroyed thirteen saloons, six hotels, a bank, a theater, eighteen office structures (many doctors and lawyers, and the newspaper), three livery stables, and over thirty other stores and shops.

[8] In 1892, mine owners in the Coeur d'Alenes found the usual investor pressure for profits exacerbated by increased railroad freight rates.

The immediate costs were three men dead on each side and the total destruction of the Frisco ore mill, about four miles northeast of Wallace.

During the Coeur d'Alene, Idaho labor confrontation of 1899 attackers murdered a non-union miner and killed one of their own by "friendly fire."

Alarmed by the size of attacking force – perhaps as many as a thousand men – Governor Frank Steunenberg imposed martial law.

They were proud of their extensive electric light system, substantial amounts of paved streets and the most building activity the city had ever seen.

However, one third of the town of Wallace was destroyed by the Great Fire of 1910, which burned about 3,000,000 acres (12,141 km2; 4,688 sq mi) in Washington, Idaho, and Montana.

[21][22] Although set back by the devastation, the city soon resumed its growth, aided by strong demand for lead during World War I.

[26] Throughout the rest of the country, progressive era politics drove red-light districts underground, but madams in Wallace enjoyed unprecedented status as influential businesswomen, community leaders, and philanthropists.

That and creation of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) put heavy pressure on mining operations, including those in the Coeur d'Alenes.

When the Bunker Hill smelter in Kellogg shut down in 1981, the Silver Valley lost a vast number of jobs, three-quarters of all the regional mining employment by some estimates.

[38] The Oasis Bordello Museum is dedicated to the history of sex work; housed in a former brothel, curious tourists or nostalgic former patrons can tour the upstairs, which has been preserved as it was when the women left.

[39] The former Lux Rooms has been repurposed into a boutique inn, and it also has many elements preserved from its brothel roots, including floor-to-ceiling gold veined mirrors.

[42] Regular annual events in Wallace include the Blues Fest, Statehood Day Parade, Huckleberry Festival 5k Walk/Run, Under the Freeway Flea Market, Gyro Days, Center Of The Universe Re-Dedication, Fall for History, Extreme SkiJor, and Home for the Holidays Christmas Festival.

The Northern Pacific Railway approached Wallace from the east with its branch over Lookout Pass to the NP mainline at St. Regis, Montana.

Union Pacific continued operating the Wallace-Mullan segment of the NP line until abandoning the entire Plummer-Mullan route in 1992.

The FHWA had to redesign I-90 to bypass downtown because federal law protects historic places from negative effects of highway construction.

[54][55][56] On September 25, 2004, Mayor Ron Garitone proclaimed Wallace to be the center of the Universe in a tongue-in-cheek political statement aimed at the EPA.

[57] In response, the Center of the Universe manhole cover was designed and installed to symbolize Wallace's resilience and mining heritage.