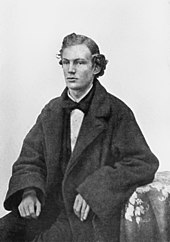

Walter Bache

He received some rudimentary musical education at his father's school, but remained a carefree, undistinguished and funloving child until he followed in Edward's footsteps.

[2] Like Edward, he studied with Birmingham City Organist James Stimpson and in August 1858, aged 16, he travelled to Germany to attend the Leipzig Conservatory.

"[8] Upon completing his piano studies in December 1861, the 19-year-old Bache travelled to Italy, staying in Milan and Florence with the intent of soaking in Italian culture before returning to England.

[9] In Florence he met Jessie Laussot, "who had founded of a flourishing musical society in the city ... and was intimately acquainted with Liszt, Wagner, Hans von Bülow and other leading musicians.

[10] She eased his way into polite society[6] and also suggested, after hearing him play at several local concerts, that he travel to Rome and seek out Liszt.

[13] Considering this "the greatest possible advantage I could have",[14] Bache wrote to Constance, I hope I have not exaggerated in talking about Liszt; he won't make me anything wonderful, so that I can come home and set the Thames on fire—not at all, so don't expect it; but—his readings or interpretations are greater and higher than anyone else's; if I can spend some time with him and go through a good deal of music with him, I shall pick up at least a great deal of his ideas;...

He also heard Liszt play his own music on many occasions in private homes, including a then-rare performance of the Piano Sonata in B minor.

[20] He also became acquainted with several young gifted musicians, including fellow Liszt pupil Giovanni Sgambati and violinist Ettore Pinelli.

[20] During this time, Bache began exploring the two-piano repertoire, especially the arrangements of Liszt's symphonic poem Les préludes and Schubert's Wanderer Fantasy, which he performed with Sgambati in concert.

[26] Before he moved to Rome, in June 1863, Bache returned to Birmingham to raise funds for the erection of a memorial window to his brother Edward.

Among these efforts was a performance of Mendelssohn's oratorio St. Paul, at which his organ playing was noted, and a solo piano recital which featured a few pieces by Liszt.

[13] Critics proved unreceptive to Liszt's music and Bache was advised to program less adventurous works if he wanted his career to succeed.

The War of the Romantics between musically conservative and liberal factions was in full swing and he found himself branded as "dangerous" for having studied with Liszt.

In 1868, they had grown to include choral works, which allowed pieces such as Liszt's Soldatenlied and choruses from Wagner's Tannhäuser and Lohengrin to be programmed.

[32] While some of the press coverage he received was positive, overall Bache faced a continual barrage of opposition and scorn from critics and fellow musicians over the music he presented.

We cannot think Les Préludes, a very difficult duett [sic] by the Abbé Liszt for two pianofortes, worth the labour bestowed on it by a couple of players so skilled as himself and Mr. Dannreuther.

[31] For these concerts, Bache programmed five of Liszt's symphonic poems, the Faust and Dante symphonies, the Thirteenth Psalm and the Legend of St.

[36] Part of this strategy of familiarity was the inclusion of the two-piano arrangements of the symphonic poems as a way to prepare audiences for the orchestral versions.

According to musicologist Alan Walker, they "are filled with insights that were both new and original for their time, and they are lavishly illustrated with music examples—a sure sign that they were aimed at a sophisticated public and were intended to have a potential life after the concert was over.

[38] These notes, along with the inclusion of the two-piano arrangements and what musicologist Michael Allis calls "a thoughtful approach to programming ... all contributed to an aggressive marketing of Liszt's new status as a composer".

By 1873, he wrote, he had to "decide whether I shall sacrifice myself entirely to the production of Liszt's orchestral and choral works (which after all can never be immortal as Bach, Beethoven and Wagner: here I feel that Bülow is right).

The Monthly Musical Record felt "There was ... good reason in introducing [it] as a duet, with a view to familiarizing hearers with it beforehand",[44] and the Musical Standard found that presenting the two-piano arrangement was "an immense help to those who wished to form a correct judgment on it at its first orchestral performance ... as it is impossible, with even the best intentions, to estimate correctly the larger works of Liszt after only one hearing.

[49] In the summer of 1867, Bache and Dannreuther formed "The Working Men's Society," a small association to promote the music of Wagner, Liszt and Schumann in England, with Karl Klindworth as an elder statesman for the group.

The first study session met in December and consisted of the "Spinning Song" from Wagner's opera The Flying Dutchman, played by Dannreuther in Liszt's piano transcription.

[61] He also played various works by Mackenzie, Mendelssohn, Mozart, Raff, Silas, Tchaikovsky and Volkmann and more familiar pieces by Bach, Beethoven and Chopin.

[67] The Musical World noted that Bache's playing of Chopin, Raff, Schumann and Weber all showed "true artistic spirit and taste".

[70] Despite receiving positive reviews for his pianism, Bache's difficulties with the critics on behalf of Liszt's music had a negative backlash on his performing career.

[71] After printed inquiries by the Musical Standard, which openly questioned why Bache's career had not advanced despite his obvious talent, he was invited in 1874 to play at the Crystal Palace.

[72] While his playing was lauded, his choice of music (the Liszt arrangement of Weber's Polonaise Brillante for piano and orchestra) was derided as astoundingly impudent.

[73] He also appeared at concerts led by Hans Richter, as organist in Liszt's symphonic poem Die Hunnenschlacht and as pianist in Beethoven's Choral Fantasy and Chopin's Second Piano Concerto.