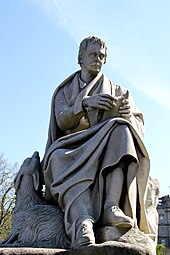

Walter Scott

Many of his works remain classics of European and Scottish literature, notably the novels Ivanhoe (1819), Rob Roy (1817), Waverley (1814), Old Mortality (1816), The Heart of Mid-Lothian (1818), and The Bride of Lammermoor (1819), along with the narrative poems Marmion (1808) and The Lady of the Lake (1810).

He was described in 1820 as "tall, well formed (except for one ankle and foot which made him walk lamely), neither fat nor thin, with forehead very high, nose short, upper lip long and face rather fleshy, complexion fresh and clear, eyes very blue, shrewd and penetrating, with hair now silvery white".

In February 1797, the threat of a French invasion persuaded Scott and many of his friends to join the Royal Edinburgh Volunteer Light Dragoons, where he served into the early 1800s,[17] and was appointed quartermaster and secretary.

Scott responded to the German interest at the time in national identity, folk culture and medieval literature,[16] which linked with his own developing passion for traditional balladry.

In his early married days Scott earned a decent living from his work as a lawyer, his salary as Sheriff-Depute, his wife's income, some revenue from his writing, and his share of his father's modest estate.

After the younger Walter was born in 1801, the Scotts moved to a spacious three-storey house at 39 North Castle Street, which remained his Edinburgh base until 1826, when it was sold by the trustees appointed after his financial ruin.

In 1798 James had published Scott's version of Goethe's Erlkönig in his newspaper The Kelso Mail, and in 1799 included it and the two Bürger translations in a privately printed anthology, Apology for Tales of Terror.

In a diary entry written at the height of his financial woes, Scott described dismay at the prospect of having to sell them: "The thoughts of parting from these dumb creatures have moved me more than any of the reflections I have put down".

)[29] Scott was able to draw on his unrivalled familiarity with Border history and legend acquired from oral and written sources beginning in his childhood to present an energetic and highly coloured picture of 16th-century Scotland, which both captivated the general public and with its voluminous notes also addressed itself to the antiquarian student.

John Marriot, William Erskine, James Skene, George Ellis, and Richard Heber: the epistles develop themes of moral positives and special delights imparted by art.

[31] The most familiar lines in the poem sum up one of its main themes: "O what a tangled web we weave,/ When first we practice to deceive"[32] Scott's meteoric poetic career peaked with his third long narrative, The Lady of the Lake (1810), which sold 20,000 copies in the first year.

[47][48] In general it is these pre-1820 novels that have drawn the attention of modern critics – especially: Waverley, with its presentation of the 1745 Jacobites drawn from the Highland clans as obsolete and fanatical idealists; Old Mortality (1816) with its treatment of the 1679 Covenanters as fanatical and often ridiculous (prompting John Galt to produce a contrasting picture in his novel Ringan Gilhaize in 1823); The Heart of Mid-Lothian (1818) with its low-born heroine Jeanie Deans making a perilous journey to Richmond in 1737 to secure a promised royal pardon for her sister, falsely accused of infanticide; and the tragic The Bride of Lammermoor (1819), with its stern account of a declined aristocratic family, with Edgar Ravenswood and his fiancée as victims of the wife of an upstart lawyer in a time of political power-struggle before the Act of Union in 1707.

This meant he was dependent on a limited range of sources, all of them printed: he had to bring together material from different centuries and invent an artificial form of speech based on Elizabethan and Jacobean drama.

The most generally esteemed of Scott's later fictions, though, are three short stories: a supernatural narrative in Scots, "Wandering Willie's Tale" in Redgauntlet (1824), and "The Highland Widow" and "The Two Drovers" in Chronicles of the Canongate (1827).

Samuel Taylor Coleridge, in a discussion of Scott's early novels, found that they derive their "long-sustained interest" from "the contest between the two great moving Principles of social Humanity – religious adherence to the Past and the Ancient, the Desire & the admiration of Permanence, on the one hand; and the Passion for increase of Knowledge, for Truth as the offspring of Reason, in short, the mighty Instincts of Progression and Free-agency, on the other.

When Waverley has his first experience of Highland ways after a raid on his Lowland host's cattle, it "seemed like a dream ... that these deeds of violence should be familiar to men's minds, and currently talked of, as falling with the common order of things, and happening daily in the immediate neighbourhood, without his having crossed the seas, and while he was yet in the otherwise well-ordered island of Great Britain.

[52] He did not create detailed plans for his stories, and the remarks by the figure of "the Author" in the Introductory Epistle to The Fortunes of Nigel probably reflect his own experience: "I think there is a dæmon who seats himself on the feather of my pen when I begin to write, and leads it astray from the purpose.

Characters expand under my hand; incidents are multiplied; the story lingers, while the materials increase – my regular mansion turns out a Gothic anomaly, and the work is complete long before I have attained the point I proposed."

By then Scott's health was failing, and on 29 October 1831, in a vain search for improvement, he set off on a voyage to Malta and Naples on board HMS Barham, a frigate put at his disposal by the Admiralty.

In 1817 as part of the land purchases Scott bought the nearby mansion-house of Toftfield for his friend Adam Ferguson to live in along with his brothers and sisters and on which, at the ladies' request, he bestowed the name of Huntlyburn.

Scott's orchestration of King George IV's visit to Scotland, in 1822, was a pivotal event intended to inspire a view of his home country that accentuated the positive aspects of the past while allowing the age of quasi-medieval blood-letting to be put to rest, while envisioning a more useful, peaceful future.

Scott is now increasingly recognised not only as the principal inventor of the historical novel and a key figure in the development of Scottish and world literature, but also as a writer of a depth and subtlety who challenges his readers as well as entertaining them.

[96] Victor Hugo, in his 1823 essay, Sir Walter Scott: Apropos of Quentin Durward, writes: Surely there is something strange and marvelous in the talent of this man who disposes of his reader as the wind disposes of a leaf; who leads him at his will into all places and into all times; unveils for him with ease the most secret recesses of the heart, as well as the most mysterious phenomena of nature, as well as the obscurest pages of history; whose imagination caresses and dominates all other imaginations, clothes with the same astonishing truth the beggar with his rags and the king with his robes, assumes all manners, adopts all garbs, speaks all languages; leaves to the physiognomy of the ages all that is immutable and eternal in their lineaments, traced there by the wisdom of God, and all that is variable and fleeting, planted there by the follies of men; does not force, like certain ignorant romancers, the personages of the past to colour themselves with our brushes and smear themselves with our varnish; but compels, by his magic power, the contemporary reader to imbue himself, at least for some hours, with the spirit of the old times, today so much scorned, like a wise and adroit adviser inviting ungrateful children to return to their father.

A fastidious mass of descriptions of bric-a-brac ... and castoff things of every sort, armor, tableware, furniture, gothic inns, and melodramatic castles where lifeless mannequins stalk about, dressed in leotards.

[100] In Jane Austen's Persuasion (1817) Anne Elliot and Captain James Benwick discuss the "richness of the present age" of poetry, and whether Marmion or The Lady of the Lake is the more preferred work.

Rob Roy is set "in the wilds of Northumberland, among the uncouth and quarrelsome squirearchical Osbaldistones", while Cathy Earnshaw "has strong similarities with Diana Vernon, who is equally out of place among her boorish relations" (Barker p. 501).

In the richness of his invention and memory, in the infinitude of his knowledge, in his improvidence for the future, in the skill with which he answers, or rather parries, sudden questions, in his low-voiced pathos and his resounding merriment, he is identical with the ideal fireside chronicler.

He wrote that he was "a faithful student of the Scottish ballads, and had always envied Sir Walter the delight of tracing them out amid their own heather, and of writing them down piecemeal from the lips of aged crones."

"[111] He goes on to coin the term "Sir Walter Scott disease", describing a respect for aristocracy, a social acceptance of duels and vendettas, and a taste for fantasy and romanticism, which he blames for the South's lack of advancement.

In Mother Night (1961) by Kurt Vonnegut Jr., memoirist and playwright Howard W. Campbell Jr. prefaces his text with the six lines beginning "Breathes there the man..." In Knights of the Sea (2010) by Canadian author Paul Marlowe, there are several references to Marmion, as well as an inn named after Ivanhoe, and a fictitious Scott novel entitled The Beastmen of Glen Glammoch.