Spectral sequence

The limit of this infinite process was essentially the same as the cohomology groups of the original sheaf.

While their theoretical importance has decreased since the introduction of derived categories, they are still the most effective computational tool available.

Unfortunately, because of the large amount of information carried in spectral sequences, they are difficult to grasp.

This information is usually contained in a rank three lattice of abelian groups or modules.

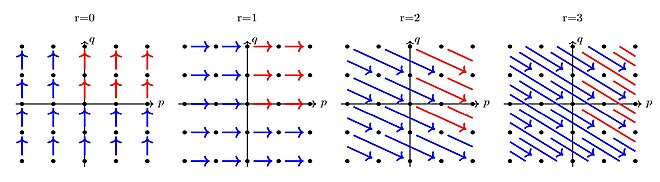

[citation needed] In reality spectral sequences mostly occur in the category of doubly graded modules over a ring R (or doubly graded sheaves of modules over a sheaf of rings), i.e. every sheet is a bigraded R-module

Depending upon the spectral sequence, the boundary map on the first sheet can have a degree which corresponds to r = 0, r = 1, or r = 2.

Mostly the objects we are talking about are chain complexes, that occur with descending (like above) or ascending order.

), one receives the definition of a homological spectral sequence analogously to the cohomological case.

An object C• in an abelian category of chain complexes naturally comes with a differential d. Let r0 = 0, and let E0 be C•.

, when the coefficient group is a ring R. It has the multiplicative structure induced by the cup products of fibre and base on the

In algebraic geometry, spectral sequences are usually constructed from filtrations of cochain complexes.

Another technique for constructing spectral sequences is William Massey's method of exact couples.

Despite this they are unpopular in abstract algebra, where most spectral sequences come from filtered complexes.

To pass to the next sheet of the spectral sequence, we will form the derived couple.

A very common type of spectral sequence comes from a filtered cochain complex, as it naturally induces a bigraded object.

are exactly the image of the elements which the differential pushes up zero levels in the filtration.

In other words, the spectral sequence should satisfy and we should have the relationship For this to make sense, we must find a differential

Determining differentials or finding ways to work around them is one of the main challenges to successfully applying a spectral sequence.

A double complex is a collection of objects Ci,j for all integers i and j together with two differentials, d I and d II.

need not exist in the category, but this is usually a non-issue since for example in the category of modules such limits exist or since in practice a spectral sequence one works with tends to degenerate; there are only finitely many inclusions in the sequence above.)

In particular, if the filtration is finite and consists of exactly r nontrivial steps, then the spectral sequence degenerates after the rth sheet.

To describe the abutment of our spectral sequence in more detail, notice that we have the formulas: To see what this implies for

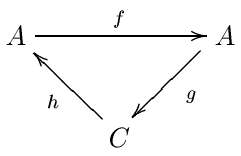

Choose a short exact sequence of cochain complexes 0 → A• → B• → C• → 0, and call the first map f• : A• → B•.

Using the abutment for a filtered complex, we find that: In general, the two gradings on Hp+q(T(C•,•)) are distinct.

Since projective modules are flat, taking the tensor product with a projective module commutes with taking homology, so we get: Since the two complexes are resolutions, their homology vanishes outside of degree zero.

-page The differentials on the second page have degree (-2, 1), so they are of the form These maps are all zero since they are hence the spectral sequence degenerates:

Putting everything together, one gets:[8] The computation in the previous section generalizes in a straightforward way.

With an obvious notational change, the type of the computations in the previous examples can also be carried out for cohomological spectral sequence.

for every p < 0, then there is a sequence of monomorphisms: The transgression is a not necessarily well-defined map: induced by

Determining these maps are fundamental for computing many differentials in the Serre spectral sequence.