Battle axe

The hardwood handles of military axes came to be reinforced with metal bands called langets, so that an enemy warrior could not cut the shaft.

They produced several varieties, including specialized throwing axes (see francisca) and "bearded" axes or "skeggox" (so named for their trailing lower blade edge which increased cleaving power and could be used to catch the edge of an opponent's shield and pull it down, leaving the shield-bearer vulnerable to a follow-up blow).

[citation needed] Viking axes may have been wielded with one hand or two, depending on the length of the plain wooden haft.

Technological development continued in the Neolithic period with the much wider usage of hard stones in addition to flint and chert and the widespread use of polishing to improve axe properties.

Many axe heads found were probably used primarily as mauls to split wood beams, and as sledgehammers for construction purposes (such hammering stakes into the ground, for example).

Some of them were suited for practical use as infantry weapons while others were clearly intended to be brandished as symbols of status and authority, judging by the quality of their decoration.

[citation needed] The Barbarian tribes that the Romans encountered north of the Alps did include iron war axes in their armories, alongside swords and spears.

Battle axes were very common in Europe in the Migration Period and the subsequent Viking Age, and they famously figure on the 11th-century Bayeux Tapestry, which depicts Norman mounted knights pitted against Anglo-Saxon infantrymen.

[5] Richard the Lionheart was often recorded in Victorian times wielding a large war axe, though references are sometimes wildly exaggerated as befitted a national hero: "Long and long after he was quiet in his grave, his terrible battle-axe, with twenty English pounds of English steel in its mighty head..." – A Child's History of England by Charles Dickens.

[8] Robert the Bruce, King of Scotland, used an axe to defeat Henry de Bohun in single combat at the start of the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314.

Steel plate-armor covering almost all of a knight's body, and incorporating features specifically designed to defeat axe and sword blades, become more common in the late 14th and early 15th century.

Increasingly daggers called misericords were carried which enabled a sharp point to be thrust though gaps in armour if an opponent was disabled or being grappled with.

Swords styles became more diverse – from the two-handed zweihänders to more narrow thrusting instruments with sharply pointed tips, capable of penetrating any "chinks in the armour" of a fully encased opponent: for example, the estoc.

[citation needed] A sharp, sometimes curved pick was often fitted to the rear of the battle axe's blade to provide the user with a secondary weapon of penetration.

Similarly, the war hammer evolved in late-medieval times with fluted or spiked heads, which would help a strike to "bite" into the armour and deliver its energy through to the wearer, rather than glance off the armor's surface.

There are many accounts of plate armored knights being struck with said weapons and while the armour was damaged, the individual underneath survived and in some cases completely unharmed.

[12] Battle axes also came to figure as heraldic devices on the coats of arms of several English and mainland European families.

Battle axes were eventually phased out at the end of the 16th century as military tactics began to revolve increasingly around the use of gunpowder.

The Norwegian peasant militia battle axe, much more wieldy than the pike or halberd and yet effective against mounted enemies, was a popular choice.

Many such weapons were ornately decorated, and yet their functionality shows in the way that the axe head was mounted tilting upwards slightly, with a significant forward curve in the shaft, with the intent of making them more effective against armoured opponents by concentrating force onto a narrower spot.

[15] During Napoleonic times, and later on in the 19th century, farriers in army service carried long and heavy axes as part of their kit.

Although these could be used in an emergency for fighting, their primary use was logistical: the branded hooves of deceased military horses needed to be removed in order to prove that they had indeed died (and had not been stolen).

[17] The tabar became one of the main weapons throughout the Middle East, and was always carried at a soldier's waist not only in Persia but Egypt, and the Arab world from the time of the Crusades.

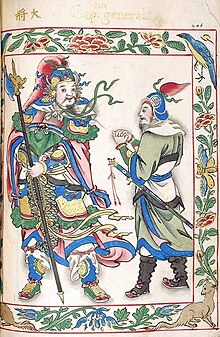

[19] A well known novel from the Ming dynasty (1368–1644) knows as the Outlaws of the Marsh (or the Water Margin - Shui Hu Zhuan 水浒传) features a character known as Li Kui, the Black Whirlwind who wields two axes and fights naked.

The Green Standard Army among the Eight Banners used double axes weighing 0.54 kg (1.2 lb) each, with a length of 50 cm (20 in).

The panabas (also known as nawi among some ethnic groups) is a traditional battle axe favored by the Moro and Lumad tribes of Mindanao, Philippines.