Interstellar medium

Although the density of atoms in the ISM is usually far below that in the best laboratory vacuums, the mean free path between collisions is short compared to typical interstellar lengths, so on these scales the ISM behaves as a gas (more precisely, as a plasma: it is everywhere at least slightly ionized), responding to pressure forces, and not as a collection of non-interacting particles.

Field, Goldsmith & Habing (1969) put forward the static two phase equilibrium model to explain the observed properties of the ISM.

McKee & Ostriker (1977) added a dynamic third phase that represented the very hot (T ~ 106 K) gas that had been shock heated by supernovae and constituted most of the volume of the ISM.

In contrast, once the temperature falls to O(105 K) with correspondingly higher density, protons and electrons can recombine to form hydrogen atoms, emitting photons which take energy out of the gas, leading to runaway cooling.

OB stars, and also cooler ones, produce many more photons with energies below the Lyman limit, which pass through the ionized region almost unabsorbed.

Photons with E > 4 eV or so can break up molecules such as H2 and CO, creating a photodissociation region (PDR) which is more or less equivalent to the Warm neutral medium.

Initially the gas is still at molecular cloud densities, and so at vastly higher pressure than the ISM average: this is a classical H II region.

The vertical scale height of the ISM is set in roughly the same way as the Earth's atmosphere, as a balance between the local gravitation field (dominated by the stars in the disk) and the pressure.

Since the angular velocity declines with increasing distance from the centre, any ISM feature, such as giant molecular clouds or magnetic field lines, that extend across a range of radius are sheared by differential rotation, and so tend to become stretched out in the tangential direction; this tendency is opposed by interstellar turbulence (see below) which tends to randomize the structures.

Some elliptical galaxies do show evidence for a small disk component, with ISM similar to spirals, buried close to their centers.

Astronomers describe the ISM as turbulent, meaning that the gas has quasi-random motions coherent over a large range of spatial scales.

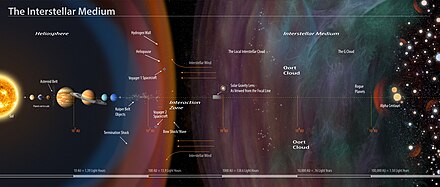

According to the researchers, this implies that "the density gradient is a large-scale feature of the VLISM (very local interstellar medium) in the general direction of the heliospheric nose".

These effects are caused by scattering and absorption of photons and allow the ISM to be observed with the naked eye in a dark sky.

The apparent rifts that can be seen in the band of the Milky Way – a uniform disk of stars – are caused by absorption of background starlight by dust in molecular clouds within a few thousand light years from Earth.

Extinction provides one of the best ways of mapping the three-dimensional structure of the ISM, especially since the advent of accurate distances to millions of stars from the Gaia mission.

The absorption gradually decreases with increasing photon energy, and the ISM begins to become transparent again in soft X-rays, with wavelengths shorter than about 1 nm.

However, the interstellar radiation field is typically much weaker than a medium in thermodynamic equilibrium; it is most often roughly that of an A star (surface temperature of ~10,000 K) highly diluted.

Thus metre-wavelength observations show H II regions as cool spots blocking the bright background emission from Galactic synchrotron radiation, while at decametres the entire galactic plane is absorbed, and the longest radio waves observed, 1 km, can only propagate 10-50 parsecs through the Local Bubble.

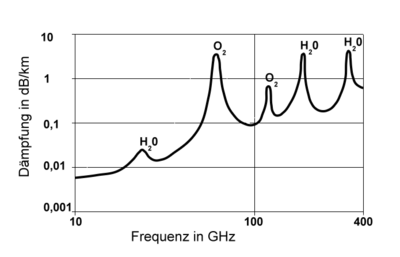

Exceptionally dense nebulae can become optically thick at centimetre wavelengths: these are just-formed and so both rare and small ('Ultra-compact H II regions') The general transparency of the ISM to radio waves, especially microwaves, may seem surprising since radio waves at frequencies > 10 GHz are significantly attenuated by Earth's atmosphere (as seen in the figure).

While vortex theory did not survive the success of Newtonian physics, an invisible luminiferous aether was re-introduced in the early 19th century as the medium to carry light waves; e.g., in 1862 a journalist wrote: "this efflux occasions a thrill, or vibratory motion, in the ether which fills the interstellar spaces.

[21] Huggins had a private observatory with an 8-inch telescope, with a lens by Alvan Clark; but it was equipped for spectroscopy, which enabled breakthrough observations.

[23] These holes are now known as dark nebulae, dusty molecular clouds silhouetted against the background star field of the galaxy; the most prominent are listed in his Barnard Catalogue.

The first direct detection of cold diffuse matter in interstellar space came in 1904, when Johannes Hartmann observed the binary star Mintaka (Delta Orionis) with the Potsdam Great Refractor.

[27] Interstellar sodium was detected by Mary Lea Heger in 1919 through the observation of stationary absorption from the atom's "D" lines at 589.0 and 589.6 nanometres towards Delta Orionis and Beta Scorpii.

[28] In the series of investigations, Viktor Ambartsumian introduced the now commonly accepted notion that interstellar matter occurs in the form of clouds.

[29] Subsequent observations of the "H" and "K" lines of calcium by Beals (1936) revealed double and asymmetric profiles in the spectra of Epsilon and Zeta Orionis.

The following year, the Norwegian explorer and physicist Kristian Birkeland wrote: "It seems to be a natural consequence of our points of view to assume that the whole of space is filled with electrons and flying electric ions of all kinds.

It does not seem unreasonable therefore to think that the greater part of the material masses in the universe is found, not in the solar systems or nebulae, but in 'empty' space" (Birkeland 1913).

In September 2012, NASA scientists reported that polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), subjected to interstellar medium (ISM) conditions, are transformed, through hydrogenation, oxygenation and hydroxylation, to more complex organics, "a step along the path toward amino acids and nucleotides, the raw materials of proteins and DNA, respectively".

"[31][32] In February 2014, NASA announced a greatly upgraded database[33] for tracking polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) in the universe.