Washington Consensus

[4] Subsequent to Williamson's use of the terminology, and despite his emphatic opposition, the phrase Washington Consensus has come to be used fairly widely in a second, broader sense, to refer to a more general orientation towards a strongly market-based approach (sometimes described as market fundamentalism or neoliberalism).

Audiences the world over seem to believe that this signifies a set of neoliberal policies that have been imposed on hapless countries by the Washington-based international financial institutions and have led them to crisis and misery.

The basic ideas that I attempted to summarize in the Washington Consensus have continued to gain wider acceptance over the past decade, to the point where Lula has had to endorse most of them in order to be electable.

[10] Kate Geohegan of Harvard University's Davis Center for Russian and Eurasian Studies credited Peruvian neoliberal economist Hernando de Soto for inspiring the Washington Consensus.

[14] As noted, in spite of Williamson's reservations, the term Washington Consensus has been used more broadly to describe the general shift towards free market policies that followed the displacement of Keynesianism in the 1970s.

[16] Following the strong intervention undertaken by governments in response to market failures, a number of journalists, politicians and senior officials from global institutions such as the World Bank began saying that the Washington Consensus was dead.

The import-substitution policies that had been pursued by many developing country governments in Latin America and elsewhere for several decades had left their economies ill-equipped to expand exports at all quickly to pay for the additional cost of imported oil (by contrast, many countries in East Asia, which had followed more export-oriented strategies, found it comparatively easy to expand exports still further, and as such managed to accommodate the external shocks with much less economic and social disruption).

He attributed this limited impact to three factors: (a) the Consensus per se placed no special emphasis on mechanisms for avoiding economic crises, which proved very damaging; (b) the reforms—both those listed in his article and, a fortiori, those actually implemented—were incomplete; and (c) the reforms cited were insufficiently ambitious with respect to targeting improvements in income distribution, and need to be complemented by stronger efforts in this direction.

[9] The Washington Consensus resulted with the La Década Perdida or "The Lost Decade" in Latin America, when many nations in the region faced sovereign debt crises.

[32]The problems which arise with reliance on a fixed exchange rate mechanism (above) are discussed in the World Bank report Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform, which questions whether expectations can be "positively affected by tying a government's hands".

Velasco and Neut (2003)[33] "argue that if the world is uncertain and there are situations in which the lack of discretion will cause large losses, a precommitment device can actually make things worse".

[35]While President Néstor Kirchner's reliance on price controls and similar administrative measures (often aimed primarily at foreign-invested firms such as utilities) clearly ran counter to the spirit of the Consensus, his administration in fact ran an extremely tight fiscal ship and maintained a highly competitive floating exchange rate; Argentina's immediate bounce-back from crisis, further aided by abrogating its debts and a fortuitous boom in prices of primary commodities, leaves open issues of longer-term sustainability.

Additionally, President Luis Herrera Campins' economic policies led to the devaluation of the Venezuelan bolívar against the US dollar in a day that would be known as Viernes Negro (English: Black Friday).

[43] The policies centred on the establishment of an exchange-rate regime, imposing a restriction on the movement of currencies, and were strongly objected to by the then-president of the Central Bank of Venezuela, Leopoldo Díaz Bruzual.

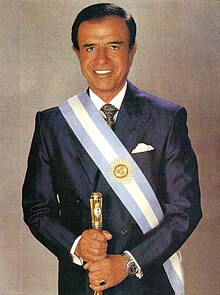

[43] Carlos Andrés Pérez based his campaign for the 1988 Venezuelan general election in his legacy of abundance during his first presidential period[46] and initially rejected liberalization policies.

[53][47][48] By late 1991, as part of the economic reforms, Carlos Andrés Pérez' administration had sold three banks, a shipyard, two sugar mills, an airline, a telephone company and a cell phone band, receiving a total of US$2,287 million.

[54] The most remarkable auction was CANTV's, a telecommunications company, which was sold at the price of US$1,885 million to the consortium composed of American AT&T International, General Telephone Electronic and the Venezuelan Electricidad de Caracas and Banco Mercantil.

[54] The Caracazo and previous inequality in Venezuela were used to justify the subsequent 1992 Venezuelan coup d'état attempts and led to the rise of Hugo Chávez's Revolutionary Bolivarian Movement-200,[56] who in 1982 had promised to depose the bipartisanship governments.

Success stories in Sub-Saharan Africa during the 1990s were relatively few and far in between, and market-oriented reforms by themselves offered no formula to deal with the growing public health emergency in which the continent became embroiled.

The cases of East Asian states such as Korea and Taiwan are known as a success story in which their remarkable economic growth was attributed to a larger role of the government by undertaking industrial policies and increasing domestic savings within their territory.

[63]The critique laid out in the World Bank's study Economic Growth in the 1990s: Learning from a Decade of Reform (2005)[64] shows how far discussion has come from the original ideas of the Washington Consensus.

Gobind Nankani, a former vice-president for Africa at the World Bank, wrote in the preface: "there is no unique universal set of rules.... [W]e need to get away from formulae and the search for elusive 'best practices'...." (p. xiii).

[66][67] A 2001 study by economist Steven Rosefielde posits that there were 3.4 million premature deaths in Russia from 1990 to 1998, which he party blames on the shock therapy imposed by the Washington Consensus.

[69] Many Sub-Saharan African's economies failed to take off during the 1990s, in spite of efforts at policy reform, changes in the political and external environments, and continued heavy influx of foreign aid.

[71] This view asserts that countries such as Brazil, Chile, Peru and Uruguay, largely governed by parties of the left in recent years, did not—whatever their rhetoric—in practice abandon most of the substantive elements of the Consensus.

[74] This includes improving the investment climate and eliminating red tape (especially for smaller firms), strengthening institutions (in areas like justice systems), fighting poverty directly via the types of Conditional Cash Transfer programs adopted by countries like Mexico and Brazil, improving the quality of primary and secondary education, boosting countries' effectiveness at developing and absorbing technology, and addressing the special needs of historically disadvantaged groups including indigenous peoples and Afro-descendant populations across Latin America.

[77] Some European and Asian economists suggest that "infrastructure-savvy economies" such as Norway, Singapore, and China have partially rejected the underlying Neoclassical "financial orthodoxy" that characterizes the Washington Consensus, instead initiating a pragmatist development path of their own[78] based on sustained, large-scale, government-funded investments in strategic infrastructure projects: "Successful countries such as Singapore, Indonesia, and South Korea still remember the harsh adjustment mechanisms imposed abruptly upon them by the IMF and World Bank during the 1997–1998 'Asian Crisis' […] What they have achieved in the past 10 years is all the more remarkable: they have quietly abandoned the Washington Consensus by investing massively in infrastructure projects […] this pragmatic approach proved to be very successful".

[79] While opinion varies among economists, Rodrik pointed out what he claimed was a factual paradox: while China and India increased their economies' reliance on free market forces to a limited extent, their general economic policies remained the exact opposite to the Washington Consensus' main recommendations.

For decades, the World Bank and donor nations pressed Malawi, a predominantly rural country in Africa, to cut back or eliminate government fertilizer subsidies to farmers.

World Bank experts also urged the country to have Malawi farmers shift to growing cash crops for export and to use foreign exchange earnings to import food.