Watchmen

Watchmen is a comic book limited series by the British creative team of writer Alan Moore, artist Dave Gibbons, and colorist John Higgins.

All but the last issue feature supplemental fictional documents that add to the series' backstory and the narrative is intertwined with that of another story, an in-story pirate comic titled Tales of the Black Freighter, which one of the characters reads.

[3] A single preview page for Watchmen, created by writer Alan Moore and artist Dave Gibbons, first appeared in the 1985 issue of DC Spotlight, the 50th anniversary special.

[18] In February 1988, DC published a limited-edition, slipcased hardcover volume, produced by Graphitti Design, that contained 48 pages of bonus material, including the original proposal and concept art.

[24] Further Watchmen imagery was added in the DC Universe: Rebirth Special #1 second printing, which featured an update to Gary Frank's cover, better revealing the outstretched hand of Doctor Manhattan in the top right corner.

Moore reasoned that MLJ Comics' Mighty Crusaders might be available for such a project, so he devised a murder mystery plot which would begin with the discovery of the body of the Shield in a harbor.

"[31] After receiving the go-ahead to work on the project, Moore and Gibbons spent a day at the latter's house creating characters, crafting details for the story's milieu and discussing influences.

[43] In fact, Gibbons only suggested one single change to the script – a compression of Ozymandias' narration while he was preventing a sneak attack by Rorschach – as he felt that the dialogue was too long to fit with the length of the action; Moore agreed and re-wrote the scene.

Their existence in this version of the United States is shown to have dramatically affected and altered the outcomes of real-world events such as the Vietnam War and the presidency of Richard Nixon.

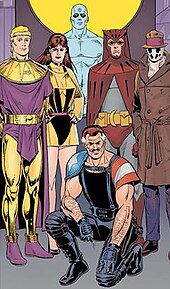

Believing that Blake's murder could be part of a larger plot against costumed adventurers, Rorschach seeks out and warns four of his retired comrades: shy inventor Daniel Dreiberg, formerly the second Nite Owl; the superpowered and emotionally detached Jon Osterman, codenamed "Doctor Manhattan"; Doctor Manhattan's lover Laurie Juspeczyk, the second Silk Spectre; and Adrian Veidt, once the hero "Ozymandias", and now a successful businessman.

Neglected in her relationship with the once-human Manhattan, whose godlike powers have left him emotionally detached from ordinary people, and no longer kept on retainer by the government, Juspeczyk stays with Dreiberg.

When Manhattan and Juspeczyk arrive back on Earth, they are confronted by mass destruction and death in New York, with a gigantic squid-like creature, created by Veidt's laboratories, dead in the middle of the city.

Back in New York, the editor at New Frontiersman asks his assistant to find some filler material from the "crank file", a collection of rejected submissions to the paper, many of which have not yet been reviewed.

With Watchmen, Alan Moore's intention was to create four or five "radically opposing ways" to perceive the world and to give readers of the story the privilege of determining which one was most morally comprehensible.

[45] The artist also cited Steve Ditko's work on early issues of The Amazing Spider-Man as an influence,[62] as well as Doctor Strange, where "even at his most psychedelic [he] would still keep a pretty straight page layout".

DC planned to insert house ads and a longer letters column to fill the space, but editor Len Wein felt this would be unfair to anyone who wrote in during the last four issues of the series.

[64] The supplemental article detailing the fictional history of Tales of the Black Freighter at the end of issue five credits real-life artist Joe Orlando as a major contributor to the series.

When he finally returns to his hometown, believing it to be already under the occupation of The Black Freighter's crew, he makes his way to his house and slays everyone he finds there, only to discover that the person he mistook for a pirate was in fact his wife.

Not every intertextual link in the series was planned by Moore, who remarked that "there's stuff in there Dave had put in that even I only noticed on the sixth or seventh read", while other "things [...] turned up in there by accident.

In The System of Comics, Thierry Groensteen described the symbol as a recurring motif that produces "rhyme and remarkable configurations" by appearing in key segments of Watchmen, notably the first and last pages of the series—spattered with blood on the first, and sauce from a hamburger on the last.

'"[30] The writer stated in the introduction to the Graffiti hardcover of Watchmen that while writing the series he was able to purge himself of his nostalgia for superheroes, and instead he found an interest in real human beings.

He considers Watchmen and Frank Miller's Batman: The Dark Knight Returns to be "the first instances [...] of [a] new kind of comic book [...] a first phase of development, the transition of the superhero from fantasy to literature.

[80] The deconstructive nature of Watchmen is, Klock notes, played out on the page also as, "[l]ike Alan Moore's kenosis, [Veidt] must destroy, then reconstruct, in order to build 'a unity which would survive him.

Speaking at the 1985 San Diego Comic-Con, Moore said: "The way it works, if I understand it, is that DC owns it for the time they're publishing it, and then it reverts to Dave and me, so we can make all the money from the Slurpee cups.

[40] DC offered Moore and Gibbons chances to publish prequels to the series, such as Rorschach's Journal or The Comedian's Vietnam War Diary, as well as hinting at the possibility of other authors using the same universe.

Tales of the Comedian's Vietnam War experiences were floated because The 'Nam was popular at the time, while another suggestion was, according to Gibbons, for a "Nite Owl/Rorschach team" (in the manner of Randall and Hopkirk (Deceased)).

[97] Gibbons was more attracted to the idea of a Minutemen series because it would have "[paid] homage to the simplicity and unsophisticated nature of Golden Age comic books—with the added dramatic interest that it would be a story whose conclusion is already known.

"[149] In 2008, Entertainment Weekly placed Watchmen at number 13 on its list of the best 50 novels printed in the last 25 years, describing it as "The greatest superhero story ever told and proof that comics are capable of smart, emotionally resonant narratives worthy of the label 'literature'.

[152] In his review of the Absolute Edition of the collection, Dave Itzkoff of The New York Times wrote that the dark legacy of Watchmen, "one that Moore almost certainly never intended, whose DNA is encoded in the increasingly black inks and bleak storylines that have become the essential elements of the contemporary superhero comic book," is "a domain he has largely ceded to writers and artists who share his fascination with brutality but not his interest in its consequences, his eagerness to tear down old boundaries but not his drive to find new ones.

[154] In 2009, Lydia Millet of The Wall Street Journal contested that Watchmen was worthy of such acclaim, and wrote that while the series' "vividly drawn panels, moody colors and lush imagery make its popularity well-deserved, if disproportionate", that "it's simply bizarre to assert that, as an illustrated literary narrative, it rivals in artistic merit, say, masterpieces like Chris Ware's 'Acme Novelty Library' or almost any part of the witty and brilliant work of Edward Gorey".