Waterloo campaign

Rather than wait for the Coalition to invade France, Napoleon decided to attack his enemies and hope to defeat them in detail before they could launch their combined and coordinated invasion.

On the night of 17 June the Anglo-allied army turned and prepared for battle on a gentle escarpment, about 1 mile (1.6 km) south of the village of Waterloo.

After the defeat at Waterloo, Napoleon chose not to remain with the army and attempt to rally it, but returned to Paris to try to secure political support for further action.

The next day Louis XVIII was restored to the French throne, and a week later on 15 July Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Lewis Maitland of HMS Bellerophon.

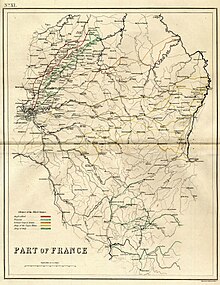

Under the terms of the peace treaty of November 1815, Coalition forces remained in Northern France as an army of occupation under the command of the Duke of Wellington.

[4] Some time after the allies began mobilising, it was agreed that the planned invasion of France was to commence on 1 July 1815,[6] much later than both Blücher and Wellington would have liked as both their armies were ready in June, ahead of the Austrians and Russians; the latter were still some distance away.

Last, the L'Armee du Nord was placed on the border with the United Netherlands to defeat the British, Dutch and Prussian forces if they dared to attack.

The French drove in Coalition outposts and secured Napoleon's favoured "central position" – at the junction between Wellington's army to his north-west, and Blücher's Prussians to his north-east.

Wellington ordered his army to concentrate around the divisional headquarters, but was still unsure whether the attack in Charleroi was a feint and the main assault would come through Mons.

Graf von Zieten's I Corps rearguard action on 15 June held up Napoleon's advance, giving Blücher the opportunity to concentrate his forces in the Sombreffe position, which had been selected earlier for its good defensive attributes.

[23] Napoleon placed Marshal Ney in command of the French left wing and ordered him to secure the crossroads of Quatre Bras towards which Wellington was hastily gathering his dispersed army.

The next day the Allies ceded the field at Quatre Bras to consolidate their forces on more favourable ground to the north along the road to Brussels as a prelude to the Battle of Waterloo.

[26] After the fighting at Quatre Bras the two opposing commanders Ney and Wellington initially held their ground while they obtained information about what had happened at the larger Battle of Ligny.

[27] With the defeat of the Prussians Napoleon still had the initiative, for Ney's failure to take the Quatre Bras cross roads had actually placed the Anglo-allied army in a precarious position.

He took the reserves and marched with Ney in pursuit of the Duke of Wellington's Anglo-allied army, and he gave instructions to Marshal Grouchy to pursue the Prussians wherever they were going and harry them so that they had no time to reorganise.

This meant that they were incapable of preventing the Prussians moving from Wavre towards Waterloo and too far away themselves to go directly to the aid of Napoleon on 18 June should Wellington turn and fight south of Brussels.

On the morning of 18 June 1815 Napoleon sent orders to Marshal Grouchy, commander of the right wing of the Army of the North, to harass the Prussians to stop them reforming.

[32] The 4,000 Prussian cavalry, that kept up an energetic pursuit during the night of 18 June, under the guidance of Marshal Gneisenau, helped to render the victory at Waterloo still more complete and decisive; and effectually deprived the French of every opportunity of recovering on the Belgian side of the frontier and to abandon most of their cannons.

[33][34] A defeated army usually covers its retreat by a rear guard, but since France had such limited military resources, wasted away largely by Napoleon over the years, there was nothing of the kind.

The rearmost of the fugitives having reached the river Sambre, at Charleroi, Marchienne-au-Pont, and Châtelet, by daybreak of 19 June 1815, indulged themselves with the hope that they might then enjoy a short rest from the fatigues which the relentless pursuit by the Prussians had entailed upon them during the night; but their fancied security was quickly disturbed by the appearance of a few Prussian cavalry, judiciously thrown forward towards the Sambre from the Advanced Guard at Gosselies.

[35] From Charleroi, Napoleon proceeded to Philippeville; whence he hoped to be able to communicate more readily with Marshal Grouchy (who was commanding the detached and still intact right wing of the Army of the North).

[39] Napoleon arrived in Paris, three days after Waterloo (21 June), still clinging to the hope of concerted national resistance; but the temper of the chambers and of the public generally forbade any such attempt.

The first brigade of guards, under Major-general Maitland, took by storm the horn-work which covers the suburbs on the left of the Somme, and the place immediately surrendered, upon the garrison obtaining leave to retire to their homes.

In fact, though the French army was daily receiving reinforcements from the towns and depots in its route, and also from the interior, the desertion from it was so great that its number was little if any thing at all augmented.

[42] With the remainder, however, Grouchy succeeded in retreating to Paris, where he joined the wreck of the main army, the whole consisting of about 40 or 50,000 troops of the line, the wretched remains (including also all reinforcements) of 150,000 men, which fought at Quatre Bras and Waterloo.

[42] On 29 June the near approach of the Prussians, who had orders to seize Napoleon, dead or alive, caused him to retire westwards toward Rochefort, whence he hoped to reach the United States.

[40] The presence of blockading Royal Navy warships under Vice Admiral Henry Hotham with orders to prevent his escape forestalled this plan.

The fighting to the south of Paris on 2 July, was obstinate, but the Prussians finally surmounted all difficulties, and succeeded in establishing themselves firmly upon the heights of Meudon and in the village of Issy.

[48] As agreed in the convention, on 4 July, the French Army, commanded by Marshal Davoust, left Paris and proceeded on its march to the southern side of Loire.

Unable to remain in France or escape from it, Napoleon surrendered to Captain Frederick Maitland of HMS Bellerophon early in the morning of 15 July and was transported to England.