Watts riots

The riots were motivated by anger at the racist and abusive practices of the Los Angeles Police Department, as well as grievances over employment discrimination, residential segregation, and poverty in L.A.[2] On August 11, 1965, Marquette Frye, a 21-year-old African-American man, was pulled over for drunk driving.

In the Great Migration of 1915–1940, major populations of African Americans moved to Northeastern and Midwestern cities such as Detroit, Chicago, St. Louis, Cincinnati, Philadelphia, Boston, and New York City to pursue jobs in newly established manufacturing industries; to cement better educational and social opportunities; and to flee racial segregation, Jim Crow laws, violence and racial bigotry in the Southern states.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 directing defense contractors not to discriminate in hiring or promotions, opening up new opportunities for minorities.

[11][12] Los Angeles had racially restrictive covenants that prevented specific minorities from renting and buying property in certain areas, even long after the courts ruled such practices illegal in 1948 and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 was passed.

At the beginning of the 20th century, Los Angeles was geographically divided by ethnicity, as demographics were being altered by the rapid migration from the Philippines (U.S. unincorporated territory at the time) and immigration from Mexico, Japan, Korea, and Southern and Eastern Europe.

[14] Following the US entry into World War II after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the federal government removed and interned 70,000 Japanese-Americans from Los Angeles, leaving empty spaces in predominantly Japanese-owned areas.

As a result, housing in South Los Angeles became increasingly scarce, overwhelming the already established communities and providing opportunities for real estate developers.

[14] In the post-World War II era, suburbs in the Los Angeles area grew explosively as black residents also wanted to live in peaceful white neighborhoods.

The spread of African Americans throughout urban Los Angeles was achieved in large part through blockbusting, a technique whereby real estate speculators would buy a home on an all-white street, sell or rent it to a black family, and then buy up the remaining homes from Caucasians at cut-rate prices, then sell them to other black families at hefty profits.

[16] The Rumford Fair Housing Act, designed to remedy residential segregation, was overturned by Proposition 14 in 1964, which was sponsored by the California real estate industry, and supported by a majority of white voters.

After a major scandal called Bloody Christmas of 1951, Parker pushed for more independence from political pressures that would enable him to create a more professionalized police force.

[20] Marquette's brother, Ronald, a passenger in the vehicle, walked to their house nearby, bringing their mother, Rena Price, back with him to the scene of the arrest.

When Rena Price reached the intersection of Avalon Boulevard and 116th Street that evening, she scolded Frye about drinking and driving as he recalled in a 1985 interview with the Orlando Sentinel.

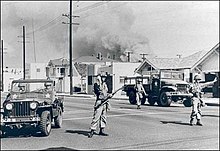

Over the next few days, rioting had then spread throughout other areas, including Pasadena, Pacoima, Monrovia, Long Beach, and even as far as San Diego, although they were very minor in comparison to Watts.

"[27] In a 1966 essay, black civil rights activist Bayard Rustin wrote: The whole point of the outbreak in Watts was that it marked the first major rebellion of Negroes against their own masochism and was carried on with the express purpose of asserting that they would no longer quietly submit to the deprivation of slum life.

[7] Three sworn personnel were killed in the riots: a Los Angeles Fire Department firefighter was struck when a wall of a fire-weakened structure fell on him while fighting fires in a store,[40] a Los Angeles County Sheriff's deputy was accidentally shot by another deputy while in a struggle with rioters,[41] and a Long Beach Police Department officer was shot by another police officer during a scuffle with rioters.

[43] After the riots, the LAPD (Los Angeles police department) examined the process of how each incident was managed by law enforcement, making a realization of the flaws of its system, when handling situations of hostile crowds, or groups.

The riots were partly a response to Proposition 14, a constitutional amendment sponsored by the California Real Estate Association and passed that had in effect repealed the Rumford Fair Housing Act.

[46] Those opinions concerning racism and discrimination were expressed three years after hearings conducted by a committee of the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights took place in Los Angeles to assess the condition of relations between the police force and minorities.

[31] After the Watts Riots, white families left surrounding nearby suburbs like Compton, Huntington Park, and South Gate in large numbers.

James E. Jones of Westminster Presbyterian Church and member of the Los Angeles Board of Education; Mrs. Robert G. Newmann, a League of Women Voters leader; and Dr. Sherman M. Mellinkoff, dean of the School of Medicine at UCLA.

[51] The McCone Commission identified the root causes of the riots to be high unemployment, poor schools, and related inferior living conditions that were endured by African Americans in Watts.

Recommendations for addressing these problems included "emergency literacy and preschool programs, improved police-community ties, increased low-income housing, more job-training projects, upgraded health-care services, more efficient public transportation, and many more."