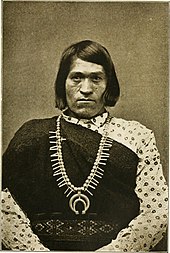

We'wha

We'wha (c. 1849–1896, various spellings) was a Zuni Native American lhamana from New Mexico, and a notable weaver and potter.

For instance, We'wha belonged to the male kachina society, a group who performed ritual dances in ceremonial masks.

[1] We'wha's friendship with anthropologist Matilda Coxe Stevenson would lead to much material on the Zuni being published.

Friends and relatives have used both male and female pronouns for We'wha, depending on stage of life and current occupation.

We'wha remained a member of her mother's tribal clan known as the donashi:kwe (the Badger People).

It was not until a few years after this that the tribe recognized We'wha's lhamana traits and his religious training was then handed over to female relatives.

The Presbyterian minister and medical doctor assigned to We'wha's tribe was a man named Taylor F. Ealy, who arrived at the village with his wife, two daughters, and an assistant teacher on October 12, 1878.

That diary entry is dated January 29, 1881,[12] and at this point We'wha is wearing skirts and doing childcare, so likely being perceived in a female role in the community.

[14] By learning English, We'wha was able to interact well with white visitors, and this helped them build a friendship with Stevenson.

If they did work for pay, "the men wearing female attire being preferred to the women on account of their strength and endurance".

George Wharton James, an expert on Native American weaving styles wrote, "She was an expert weaver, and her pole of soft stuff was laden with the work of her loom-blankets and dresses exquisitely woven, and with a delicate perception of colour-values that delighted the eye of the connoisseur".

These included activities for high society such as going to the New National Theater for a ball and participating in a tea party with Washington ladies.

Many other male Native American visitors in the nineteenth century visited the United States with hardly any attention from the public or the press.

They viewed themselves as a representative of the Zuni tribe and did their best to establish good relations with the United States government and its people to ensure the health of their ongoing alliance.

After serving as a cultural ambassador for the Zuni population in Washington, We'wha returned to the pueblo community.

Will Roscoe wrote that "he spent a month in jail for resisting soldiers sent by that same government to interfere in his community affairs.

[24] In 1896, We'wha's family was selected to host the annual Sha'lako festival and he worked to ensure everything was prepared.

These preparations included "carefully laying the stone floor in the large room where the bird-god would dance.

Through Mallery's response to a question, they explain that We'wha had a large role in representing Zuni Culture and the core element of art as a weaver.

We are a village filled with talented artists and I am absolutely grateful for this honor to represent our history and to tell it using our art."

(Zuni Pueblo guest artist Mallery Quetawki)[30]We'wha also has a page on The National Women's History Museum's website, published recently as June 2021.

[31] This page briefly covers We'wha's life and contributions to the world, describing We'wha as an individual who "left a profound legacy as a ceremonial leader, cultural ambassador, and artist who worked to preserve the Zuni way of life.

[33] Also, Paul Elliott Russell, an American writer and university professor ranked We'wha 53rd in his 1995 book The Gay 100: A Ranking of the Most Influential Gay Men and Lesbians, Past and Present on the Most Important Queer People in the World world history.

Matilda Coxe Stevenson, a contemporary of and close friend of We'wha, varied between masculine and feminine pronouns.

"What is important to emphasize is the fact that the berdache refers to a "distinct gender status, designated by special terms rather than the words ‘man' or ‘woman.'"