Weak and strong sustainability

One of the first pieces of work to discuss these ideas was "Blueprint for a Green Economy" by Pearce, Markandya, and Barbier, published in 1989.

Decision makers, both in theory and practice, need a concept that enables assessment in order to decide if intergenerational equity is achieved.

Weak sustainability is an idea based upon the work of Nobel laureate Robert Solow,[4][5][6] and John Hartwick.

It began as an extension of the neoclassical theory of economic growth, accounting for non-renewable natural resources as a factor of production.

[4][7] However, it only really came into the mainstream in the 1990s as the idea received more political attention as sustainable development discussions evolved in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

The Brundtland Report, for example, stated that ‘The loss of plant and animal species can greatly limit the options of future generations.

Taking that as well as the acute degradation into account, one could justify using up vast resources in an attempt to preserve certain species from extinction.

He defines sustainability as implying something about maintaining the level of human welfare (or well-being) so that it may improve, but never declines (or, not more than temporarily).

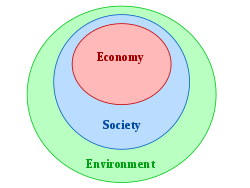

Strong sustainability does not share the notion of inter-changeability; it assumes that economic and environmental capital are complementary but not interchangeable.

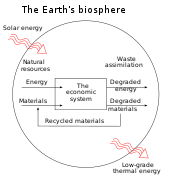

Examples include the degradation of the ozone layer, tropical forests and coral reefs if accompanied by benefits to human capital.

Statoil ASA, a state-owned Norwegian oil company invested its surplus profits from petroleum into a pension portfolio to date worth over $1 trillion.

The resultant fund allows for long-lasting income for the population in exchange for a finite resource, actually increasing the total capital available for Norway above the original levels.

In this application, Hartwick's rule would state that the pension fund was sufficient capital to offset the depletion of the oil resources.

[20] Concurrent with this extraction, Nauru's inhabitants, over the last few decades of the twentieth century, have enjoyed a high per capita income.

[21] This case presents a telling argument against weak sustainability, suggesting that a substitution of natural for man-made capital may not be reversible in the long-term.

Genuine savings measures net changes in produced, natural and human capital stocks, valued in monetary terms.

In this sense it is similar to green accounting, which attempts to factor environmental costs into the financial results of operations.

[24] Martinez-Allier's address[25] concerns over the implications of measuring weak sustainability, after results of work conducted by Pearce & Atkinson in the early 1990s.

Other inadequacies of the paradigm include the difficulties in measuring savings rates and the inherent problems in quantifying the many different attributes and functions of the biophysical world in monetary terms.

[27] By including all human and biophysical resources under the same heading of ‘capital’, the depleting of fossil fuels, reduction of biodiversity and so forth, are potentially compatible with sustainability.

According to Van Den Bergh,[30] resilience can be considered as a global, structural stability concept, based on the idea that multiple, locally stable ecosystems can exist.

This high level of sensitivity within regional systems in the face of external factors brings to attention an important inadequacy of weak sustainability.

[10] He holds that sustainability only makes sense in its 'strong' form, but that "requires subscribing to a morally repugnant and totally impracticable objective.

[clarification needed] This approach is intended to "free us from a 'zero-sum' game in which our gain is an automatic loss for future generations".

By focusing on bequests of specific rights and opportunities for future generations, we can remove ourselves from the "straightjacket of substitution and marginal tradeoffs of neoclassical theory".